Technology that breaks the mold

Spatial augmented reality uses real-time projections to expand our perception of our three-dimensional world, creating perfect illusions of fantasy. Researcher and pioneer Martin Fröhlich demonstrates just what this technology is capable of.

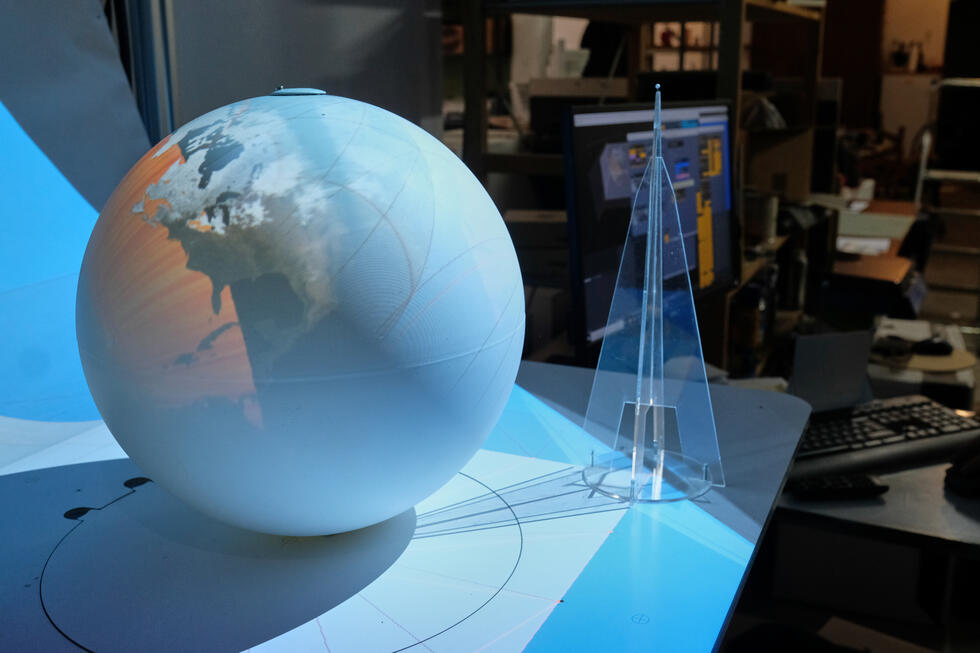

The remains of the world dangle from the ceiling like a shed snakeskin – carelessly draped over a bare light bulb. It is the macabre-looking outer layer of a geographical globe that Martin Fröhlich has hung here. “I needed a sphere,” he says laconically, smiling and pointing to the bare white globe on a small table, above which two projectors and various optical sensors are mounted. Then he switches on the projectors, launches a program on the computer, and makes a few adjustments. Suddenly, the globe fills with life: The projectors create the illusion on the surface of the sphere that you are actually looking inside it – in 3D. You can see the glowing heart of a virtual earth, with the continents floating above it. When Martin Fröhlich rotates the sphere, the land masses and the interior of the sphere move realistically in relation to each other. Regardless of your viewpoint, the illusion persists.

This wizardry goes by the name of “spatial augmented reality” (SAR). SAR transports the idea of conventional augmented reality (see box) into the third dimension and may one day even lead to what people familiar with the “Star Trek” television franchise will know as the holodeck: a completely artificially generated fantasy world where flesh-and-blood people can physically interact with virtual reality. For the time being, however, this is still a distant dream, so let’s return to what is already possible.

Playing with illusions

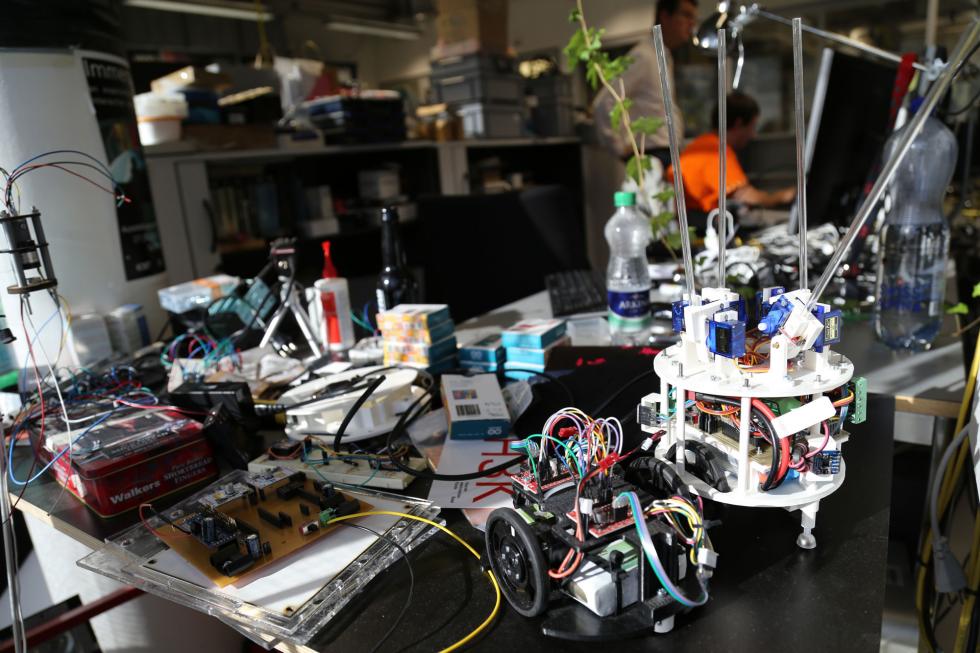

We are in a backyard garage in a residential neighborhood of Zurich, Switzerland. This is where Martin Fröhlich has set up his SAR laboratory, in the midst of trestle-mounted worktops, bookshelves brimming with boxes and equipment, surrounded by art objects, and in easy reach, the obligatory coffee machine with mugs purchased from a thrift store. Nowadays, however, he rarely uses his lab, he says. The media artist mainly researches immersive technologies and is the operational director of the Immersive Arts Space. This research group at the Zurich University of the Arts focuses on the interaction between art, design, and digital technologies; Martin Fröhlich’s specialty is projection mapping. This technology allows projections to be adapted to a two- or three-dimensional surface with pinpoint precision. Martin Fröhlich’s garage is the ideal place to demonstrate what spatial augmented reality and projection mapping are all about.

First and foremost, it involves creating optical illusions in three-dimensional space. Precisely projecting light onto objects, people, and spaces superimposes a virtual reality onto the real world and, as with the globe mentioned above, expands it to create fascinating illusions. This is also the case with “HeliumDrone”, a project with which Martin Fröhlich and his team are experimenting with real-time projections. They project images with high precision onto helium balloons that are floating freely, without incurring any overlapping or blending of the projections.

Where milliseconds count

As effortless as the illusions appear, they are based on a highly complex interplay of tracking points, sensors, cameras, projectors, and software: Data is sent back and forth at lightning speed, virtual spaces are created, surfaces are calculated, projectors are controlled. The software has to determine to within a millimeter where the projection of one projector ends and that of the next begins, where additional light is required and where there is too much light. The slightest misalignment can destroy the illusion. “I had to write the software myself; no applications existed for this yet,” Martin Fröhlich explains. The main obstacle, he adds, is the time delay, also known as latency. When a person or object moves, the projection has to track it almost instantaneously. A latency of slightly in excess of 40 milliseconds is already noticeable to the human eye. “Meanwhile, we can project onto bodies that are moving almost in real time,” Martin Fröhlich explains. This doesn’t even require super-expensive computers; a powerful gaming PC and the 3D camera from an iPhone are all it takes. However, the tracking technology is expensive.

Meanwhile, we can project onto bodies that are moving almost in real time

“Originally, I figured museums and trade shows would be interested in the possibilities of the technology,” Martin Fröhlich says. But he encountered closed doors. Instead, exciting playgrounds opened up in the arts and in theatre. “Projecting onto the faces and bodies of performers and actors is nothing new,” says Fröhlich. What is new, however, is that they can now move freely while the projection tracks them.

This is impressively demonstrated by the Immersive Arts Space’s art project “Presence&Absence”: During this dance performance, frames strung with elastic bands are used as screens. The performers move freely in front of, through, and behind these screens. Body parts that are located behind the screens are replaced by projected fantasy body parts. Even if the dancers move or tilt the screen frames, the art imagery is projected correctly. In order for the computer to recognize the positions of the dancers and screens, motion-capture technology that is widely used in the movie industry is employed.

“SAR opens doors to new realms of possibility,” Martin Fröhlich says. But it takes artists to explore these realms and spur on new technological solutions with their ideas. It is this interaction that stimulates progress. “However, the work of art must actually function and go beyond mere technical gimmickry,” he believes.

Once the benefits of blending reality and the digital world start being realized, the technology will find its way into all areas

Spatial augmented reality has also not caught on in industry yet. This in spite of the fact that there are countless potential applications: in medicine to assist during surgery, in training, in industrial production, in what is known as smart manufacturing, or in industrial design. It is conceivable, for example, to dynamically change the appearance of a car during demonstrations. Advertisements could also be projected onto moving surfaces. And in industrial manufacturing environments, SAR could help set up machines. Martin Fröhlich is convinced: “Once the benefits of blending reality and the digital world start being realized, the technology will find its way into all areas.” The crucial factor here, he says, is the balance between benefits and costs.

Willful suspension of disbelief

For the future, the researcher anticipates a growing integration of virtual reality – the technology that creates three-dimensional spaces using VR goggles such as the Oculus. It is conceivable, for example, that the wearer of VR glasses could experience an artificial reality that is simultaneously projected onto the real space in which the user is located. Seen from the outside, the user would physically be in the virtual space that they are experiencing via their glasses.

The goal is a “willful suspension of disbelief”, says Martin Fröhlich. The expression refers to the state of mind when people accept artificial space as their momentary reality. This also happens when we read a book: We are prepared to immerse ourselves in the world created by the author and to believe it. This becomes all the more fascinating when spatial augmented reality makes us believe that we are actually physically in a fantasy world. Martin Fröhlich: “We create a dream-like situation without the awareness of dreaming.”

We create a dream-like situation without the awareness of dreaming

However, according to Martin Fröhlich, it will certainly take a long time yet before anything like the holodeck from “Star Trek” is possible. Meanwhile, the old world hanging from the ceiling of his laboratory is a powerful symbol of how quickly the world is changing thanks to new illusion technologies such as SAR.

About Martin Fröhlich

Following his technical engineering apprenticeship, Martin Fröhlich (*1970) initially worked in the field of software development for various large corporations and startups in the e-commerce sector. As a digital nomad, he set out on a round-the-world trip in 1997, worked for an Internet company in Australia for three years and, after returning to Switzerland, completed a media arts degree in Aarau.

Today he works as a research associate in the Immersive Arts Space of the Department of Performing Arts & Film at the Zurich University of the Arts. Among other projects, Martin Fröhlich was involved in the spatial augmented reality installation “Uriversum”, which was produced for the inauguration of the Gotthard Tunnel.

Photos and written by: Jan Graber