Are you serious? Learning by gaming

Gaming with a serious purpose: Serious games support medical therapies, make it easier for children to learn, or encourage young people to explore art.

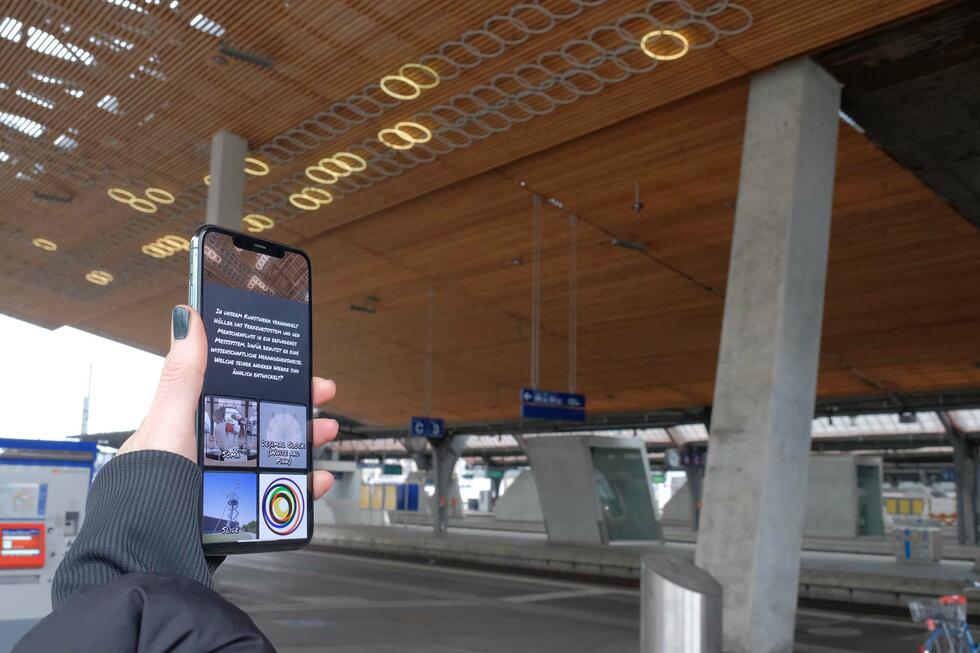

Standing in the large concourse of Zurich Main Station, Bettina Meier-Bickel looks up at the cheerful, colorful sculpture floating above her. It was created by Niki de Saint Phalle and is commonly known as “The Angel”, but its full name is “L’ange protecteur" (The Guardian Angel). She lowers her gaze to her cell phone, taps on the screen, and looks up again. All around her, people are rushing to catch their train, waiting for someone to arrive, or looking for the stop for the next bus or streetcar. The art historian pockets her phone and heads towards the rear entrance of the station, where another art installation awaits her. Bettina Meier-Bickel is testing a mobile game for which she and her business partner Karin Frei Rappenecker designed the content and which they hope will soon be played by young people on their smartphones.

The game is called “Artspotting” and falls into the genre of serious games. The main target group is schoolchildren, and the game is intended to introduce them to the world of art in a playful way. However, it will also be available to art enthusiasts of all ages.

The game uses localization data from the player’s smartphone to determine where they are and which works of art are in their vicinity. Once a work of art has been detected, “Artspotting” launches a quiz that provides background information on the object in question.

The in-game character, Panksy the pigeon, helps the player discover the artworks. If the players find a work of art, Panksy receives kernels of corn as a reward. In addition, new virtual works of art can be created using set pieces from the already discovered artwork – a function that is intended to encourage the player’s own creativity. In a first step, the game will only incorporate artworks in the vicinity of Zurich Main Station. “Artspotting” is being developed by the Swiss game studio Koboldgames, based in the town of Brugg.

Serious is popular

As an educational game, “Artspotting” is a typical representative of the serious game genre – software that uses game mechanics and rules to pursue a serious objective. Over the past ten years, this genre has become one of the most important sources of income for the Swiss video game industry. This is due to the fact that most Swiss game developers have not yet managed to tap into the full coffers of the entertainment game sector. While blockbuster games such as “Minecraft”, “Fortnite”, or the “FIFA” football game series rake in billions around the globe, the Swiss game developer scene is still very low key. Only the “Giants Software” studio based in the small town of Schlieren has managed to create an international big seller with its “Farming Simulator”. Swiss studios with a global reach can thus be counted on one hand. This is not due to a lack of skills – after all, Zurich is home to one of the world’s most renowned game design schools – but rather to scarce financial resources: There is hardly any money to be made on the small Swiss market, and the competition in the international arena is fierce. Making it there requires a great deal of self-confidence, but in Switzerland, video games are still accorded a dubious social reputation.

Not so serious games. They have proven themselves as extremely useful tools in medicine, for example in the field of rehabilitation: Arduous and repetitive therapy exercises are more fun when they are performed in the context of a game. One of the first serious games to utilize this effect was “Gabarello”: Developed by the Department of Game Design at the Zurich University of the Arts (ZHdK), the game motivates walking-impaired patients to perform walking exercises on the “Lokomat” gait training robot. The “Lokomat” controls a game character in a strange world full of surprises that can be discovered by walking around. “The acceptance of serious games has grown strongly over the past ten years,” says Ralf Mauerhofer, one of the co-founders of Koboldgames.

The acceptance of serious games has grown strongly over the past ten years

Benefits for business and research

Serious games have also established themselves in the field of learning and therapy. “School educationalists have recognized the benefits of digital learning games,” Ralf Mauerhofer says. Their insight: It is easier to retain knowledge that is taught in a playful fashion. This is particularly valuable for children: The “Fresh Food Runner” learning game, for example, teaches schoolchildren about the seasonality of fruits and vegetables. However, the focus is not only on young people: Another game created by Koboldgames in cooperation with the University of Zurich is called “uFin: The Challenge” – a serious moral game. It is designed to hone the moral awareness of people who are involved in the financial sector. Numerous serious game developers have discovered senior citizens as a target group, helping them, for example, to improve their memory or maintain their fine motor skills. The “Four Seasons” game, for example, uses a pressure-sensitive plate to enhance the gait stability of elderly people.

Last but not least, the benefits of video games have also been recognized in research: Surveys often run the risk of participants unconsciously adapting their responses to suit the researchers’ objectives. This is not the case when responses are provided within the context of a game: People respond more intuitively and directly to questions posed in this way, and as a result, their responses are more genuine.

Art on the smartphone

We have arrived at the south entrance to Zurich Main Station on Europaallee. Here, Bettina Meier-Bickel whips out her phone, looks at the app, and then at a work of art that many people see every day, but whose creator is probably known only to a few: The “Memorial to Hans Künzi” light installation was created by the artist Carsten Höller. Bettina Meier-Bickel taps on the screen. It displays information about Höller’s creation and about Hans Künzi, the former member of Zurich’s government and the father of Zurich’s S-Bahn commuter train network. Bettina Meier-Bickel and her business partner are both art historians and together, they thought about how to arouse the interest in art and culture of 15 to 18-year-olds. They were certain: The smartphone, the integral communication tool of young people, had to be a part of the experience. The game app facilitates young people’s access to the physical experience of art and it acts as a fun motivator and bridging element, she explains, adding: “I never used to care much for video games.”

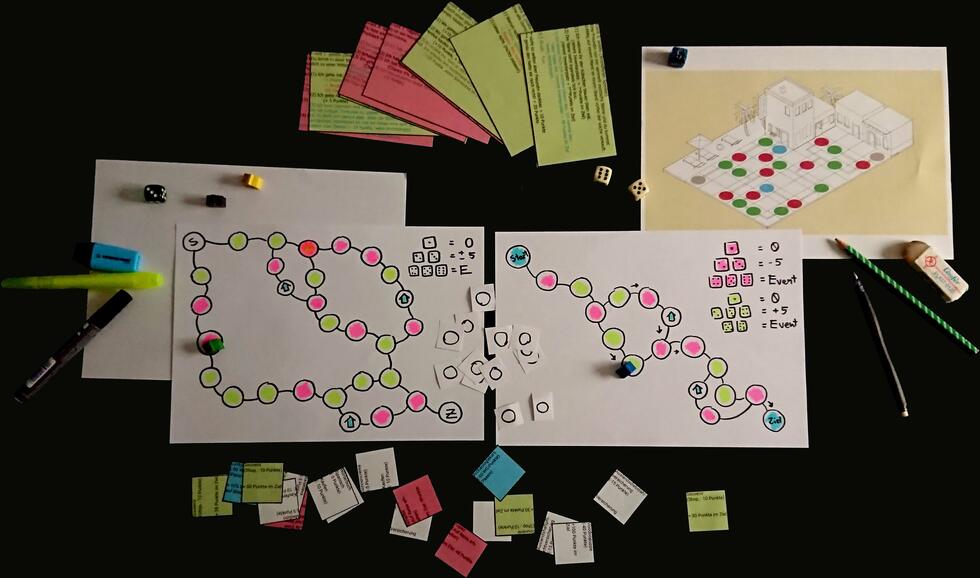

The game is still a minimal viable product – a software program that offers just enough functionality to allow it to be tested. The graphics are still rudimentary without any refinements. Funding has proven a challenge, especially since the Covid-19 pandemic, Bettina Meier-Bickel explains: “Moreover, many funding bodies in the field of the arts lack the necessary awareness of video games.”

Disappointments are not uncommon

Funding is also the big issue for Koboldgames. “You simply cannot develop a respectable serious game for less than 50,000 Swiss francs,” Ralf Mauerhofer explains. And developing a game that features a 3D world with high-quality graphics requires at least twice that amount. The most expensive game he was ever involved in, which took several years to develop, cost half a million. This is still a fraction of the budget of blockbuster games, such as “Assassin’s Creed”, which take hundreds of millions to produce. This adventure game is one of the few big-budget games that also contains a serious game element. For example, the first game in the “Assassin’s Creed” series depicted characters, buildings, and clothing from the time of the Crusades in Damascus in a meticulously accurate and largely historically correct manner. Prior to creating the game, its designers delved deep into the history books and studied the events of the time. In the meantime, the “Assassin’s Creed” series has been running for over 15 years, and each game is dedicated to a different historical era. In Switzerland, however, there is a lack of funding for such productions. “This can sometimes cause our clients to be disappointed,” Ralf Mauerhofer says. In particular when, for an investment of just a few tens of thousands or even a hundred thousand Swiss francs, they expect the photo-realistic graphics of a multimillion-dollar game. “A university simply doesn’t have several million to invest in a game,” the game designer says.

Know your target group

Back in the Zurich Main Station concourse, the city is bustling all around us. Giorgio-Lilo Salvador and Mette Regenthal, both 15 years old, are checking out “Artspotting”. They immediately grasp the game principle, and after a few steps they are standing bellow Niki de Saint-Phalle’s “Guardian Angel” and answering the quiz questions. “Super easy”, says Giorgio-Lilo absorbed in the game. After answering the questions correctly, the in-game “scanner” leads them to the statue of Alfred Escher on Bahnhofstrasse, provides some background information, and then guides them to the station’s south entrance. “It’s cool that you can use your smartphone to play with others outdoors and discuss the questions,” Mette says. Periodically, Giorgio-Lilo hits the “Scanner” button to discover Carsten Höller’s light installation. “What I like about the game is that you can’t simply read the answers to the quiz somewhere and repeat them in the game – you also have to think for yourself,” he emphasizes. Mette adds that she would primarily be interested in a serious game if it deals with an exciting topic outside of school – “something you also like to do in your free time”. “Artspotting”, for example, would be more appealing to her if it also featured graffiti art. “I would also enjoy a game about food or cooking,” says Giorgio-Lilo, who will begin his apprenticeship as a chef this summer.

Unlike movies or video games for pure entertainment, you cannot build a new audience with such games

“Good developers of serious games know their target audience very well,” says Ralf Mauerhofer from Koboldgames. The target group must also be involved in the development process from a very early stage, he adds. “Without a target audience, a serious game makes no sense.” Unlike movies or video games for pure entertainment, you cannot build a new audience with such games, he explains. The developers of “Artspotting” are also involving their target audience: Very early on, the game was tested by high school students and apprentices. This revealed considerable differences between the age groups. “At 18, you’re at a different point in life than when you’re 15,” Bettina Meier-Bickel says. Therefore, it is not yet entirely clear which age group will respond most favorably to “Artspotting”. But the serious game will definitely be educational – for everyone involved.

Koboldgames

The Swiss game design studio was founded in 2012 in the Swiss town of Olten by five game design students from the Zurich University of the Arts (ZHdK). Their very first game – “Journey of a Roach” – achieved international acclaim and was published by the German publisher Daedalic Entertainment. Subsequently, however, Koboldgames started to focus on promotional and serious games. The majority of its clients are based in the learning, training, and therapy sectors. The team of seven has since moved their offices to the small Swiss town of Brugg.

Photos and written by: Jan Graber