Tricky parts. Or how to explore the limits of the possible

The precision mechanic Martin Fischer skillfully navigates between the worlds of metalworking and art. His passion: designing and manufacturing elegant pendulum clocks, for which he requires high-precision parts. These are cut by the Swiss job shop Al-Cut using a Bystronic laser cutting machine. A visit to the curious metal workshop of a creative mind.

The bell rings loudly, brightly, and expectantly, as if someone had just rung the bell on an oversized door beckoning to be let in. The distinctive tone, however, merely signals the full hour and comes from one of the many clocks that are ticking away in Martin Fischer’s metal workshop. “Once upon a time, I wanted to become an artist,” he says with a smile that is as mischievous as it is reserved; a golden incisor flashes. “But I was pretty unsuccessful.” That is why, he says, he eventually returned to metalworking – or rather, to somewhere in between. Fischer is a wiry, athletic, and bald-headed man with striking facial features and an intensely scrutinizing, yet always open and friendly, gaze. And he has a distinct can-do attitude: He runs a metal workshop at “Gleis 70” in the outskirts of Zurich – an artists’ and craftspeople’s cooperative that wouldn’t exist without the 61-year-old.

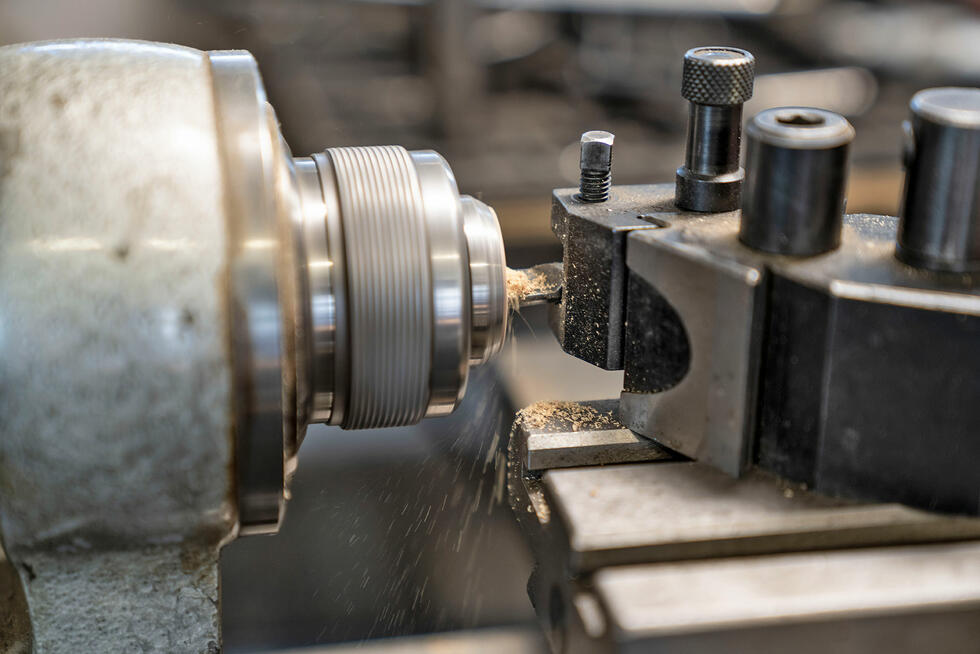

His workshop is brimming with objects of various origins. The large room overlooking the tracks of the Zurich rail yard is littered with lathes, drilling and milling machines, workbenches, welding equipment, and stockpiles of steel profiles, tubes, and rods. Years of metal dust have turned the concrete floor a cloudy black, and the air smells of iron, machine oil, and burnt iron filings. A bicycle and the legs of an old mannequin are hanging on one wall, traffic signs and other bizarre objects on another. A small disco ball is dangling in one corner above a holey tin rabbit on a rail, which has apparently already been hit by several air rifle pellets. Fischer’s light office is also home to many eye-catching objects. Next to his desk, an ultra-precise master clock is ticking away, serving as a reference timekeeper for all the other clocks in his workshop. Countless hunting trophies peer down from a wall above the glazed entrance; they were originally intended for a culinary event, which never took place – at least not yet.

Catching the horological virus in a watchmaker’s factory

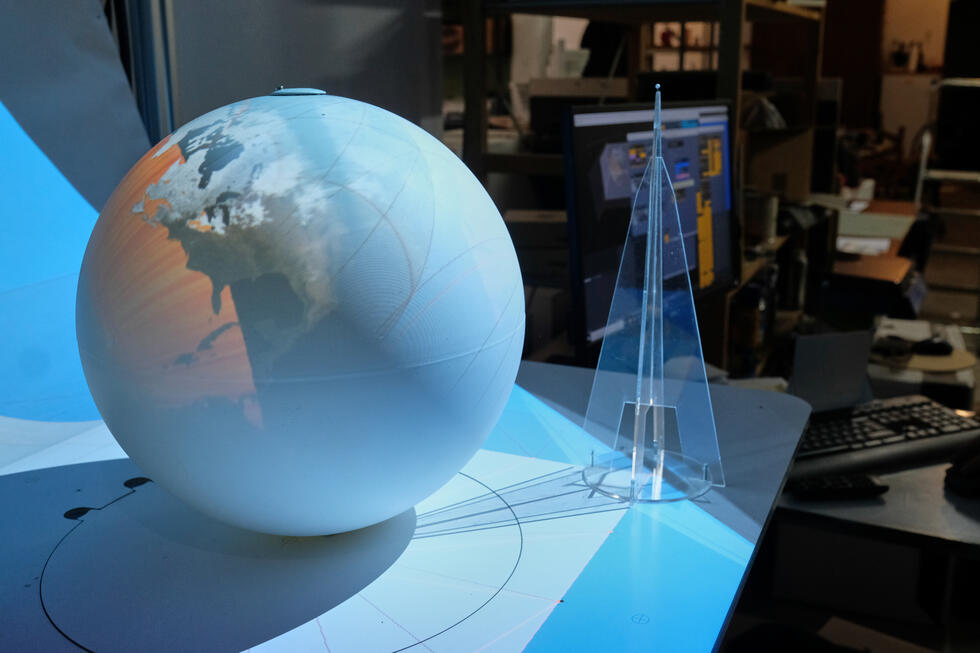

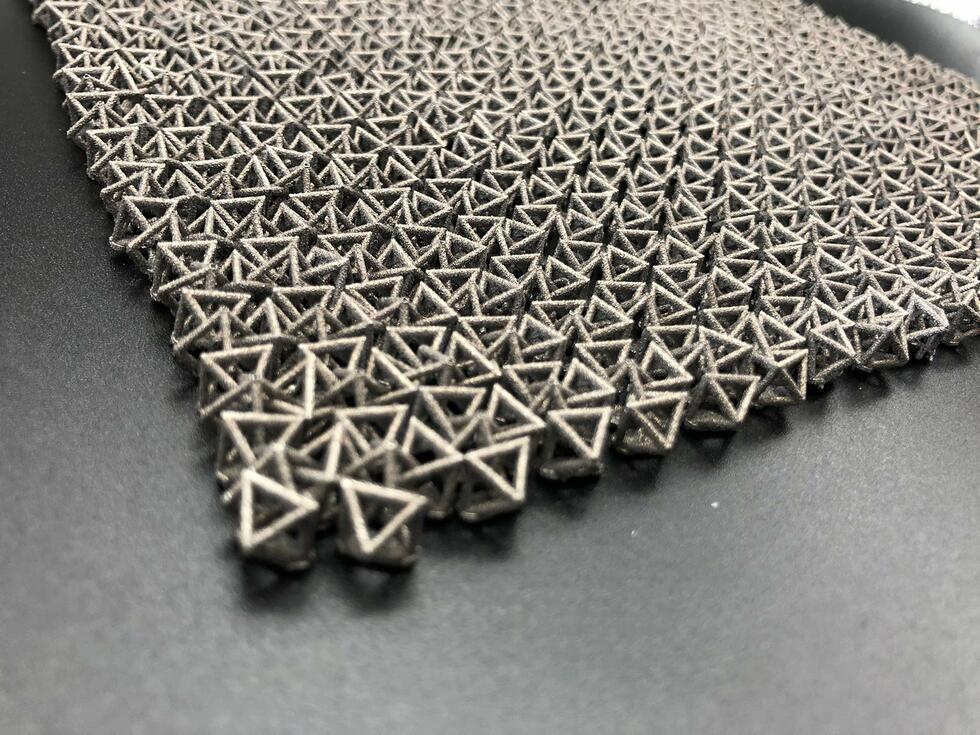

Three precisely manufactured pendulum clocks on the wall also draw the eye. The delicate metal objects with their exposed movements were designed and manufactured by Fischer from scratch. They bear witness to his striking flair for minimalist design; the clocks are second to none in terms of elegance. The most recent model – the “Clockwork 2.00B” – consists of only four interlocking cogs, a pendulum, a weight, and an escapement* consisting of the pallets and the pallets fork (see box).

It took me quite some time before I figured out how to perfect the geometry of the escapement

Fischer caught the horological virus in 2006 when he bought a building in the Swiss Jura region that used to be home to a small watchmaker’s factory. Driven by his curiosity, Fischer began to study how clocks work, learned about medieval verge escapements, and ultimately decided to try his hand at engineering a chronometer himself. “It took me quite some time before I figured out how to perfect the geometry of the escapement,” Fischer says. He probably wouldn’t have succeeded if not for a mentor who initiated him in the secrets of watchmaking. But once you get the hang of it, the rest is really just about precise metalworking, he says.

Change of scene. An industrial neighborhood in Inwil on a bright late September morning. The laser and waterjet cutting specialist Al-Cut is bustling with activity. Employees sit in offices in front of screens, walk over to the shop floor, and return with plans and spreadsheets: in short, the buzzing atmosphere of an industrial metal processing company. Toni Räber, the company’s founder and Managing Director, is a stout figure with a mottled gray beard, an alert gaze, and the bearing of an actor. He is who Martin Fischer turned to for the cutting of the components for his clock escapements. We walk through the Al-Cut’s large factory hall, which houses laser and waterjet cutting machines the size of single-car garages. “We have a whole range of Bystronic machines,” Toni Räber says as we stop in front of a ByStar Fiber 3015. The machines include three laser cutting systems, two waterjet cutters, and two press brakes (see box). “We are also testing prototypes from Bystronic,” Räber says with visible pride, as he leads us past an impressive metal warehouse back to the reception area and a display case showcasing sample parts. He points to a tiny bicycle, just two millimeters in length, on which a magnifying glass reveals all the details such as the spokes and pedals. “Lasers allow us to work with incredibly high precision, even at the smallest of dimensions,” he says.

Exploring the limits of the possible

However, the precision of the machines is not the only reason why Martin Fischer relies on Al-Cut for his clock components: It is also due to Toni Räber’s willingness to tackle challenging jobs and work together with customers to find solutions to unusual problems – for example with regard to the heat resistance of metals during the cutting process. “I really enjoy working together with customers like Martin Fischer in order to push the envelope,” he says. For Fischer’s clock escapements, for example, they first had to find the correct material. Toni Räber calls them tricky parts. They finally settled on CK45 steel, because it can be hardened after machining, in order to minimize wear in the clock movement.

I enjoy collaborating with other people, especially with artists who approach me with challenging projects. I love developing new ideas. And I like to push myself beyond my limits in order to expand my spectrum

“I appreciate Toni Räber’s understanding of materials and how he thinks ahead,” Martin Fischer says. Back in Fischer’s workshop in Zurich, he serves up a strong espresso. “I enjoy collaborating with other people, especially with artists who approach me with challenging projects. I love developing new ideas. And I like to push myself beyond my limits in order to expand my spectrum,” he says. That’s why, he explains, he didn’t immediately start working in industry after completing his apprenticeship as a polymechanic, but traveled to London to learn English. There he got to know the glass and steel artist Danny Lane, started working as his assistant, and thus first came into contact with the art world. “This experience made me want to become an artist myself,” he says. Somehow, he found his way to Tuscany, where he helped set up an art school, and then to Milan, where he tried his hand at being an artist for a year. “Absolutely unsuccessfully,” he says with a chuckle. Back in Zurich, he started doing mechanical jobs and scenery construction for a renowned theater as well as for film and theater producers – he found his way back to metalworking and a niche between the creative and the industrial world.

Accordingly, he is not only involved in the mechanical work, but also in the creative process. He does welding jobs for museums and galleries, builds lights and luminaires, constructs furniture and, together with his wife, has designed several restaurant interiors. If required for a job, he also manufactures his own high-precision tools. His main expertise, he says, lies in metalworking methods. “But it’s the hands-on tinkering that fascinates me most,” he says with a mischievousness twinkling in his eyes. Together with friends, for example, he designed and built a bazooka to launch tennis balls or fireworks, which he calls “Fischerwerke”: They are evocative of the “The Way Things Go” art film by the artist duo Fischli and Weiss. “I can spend hours experimenting,” he concludes with a grin, whereupon the hour bell sounds right on time to mark the end of our conversation.

How the “Clockwork 2.00B” pendulum clock works

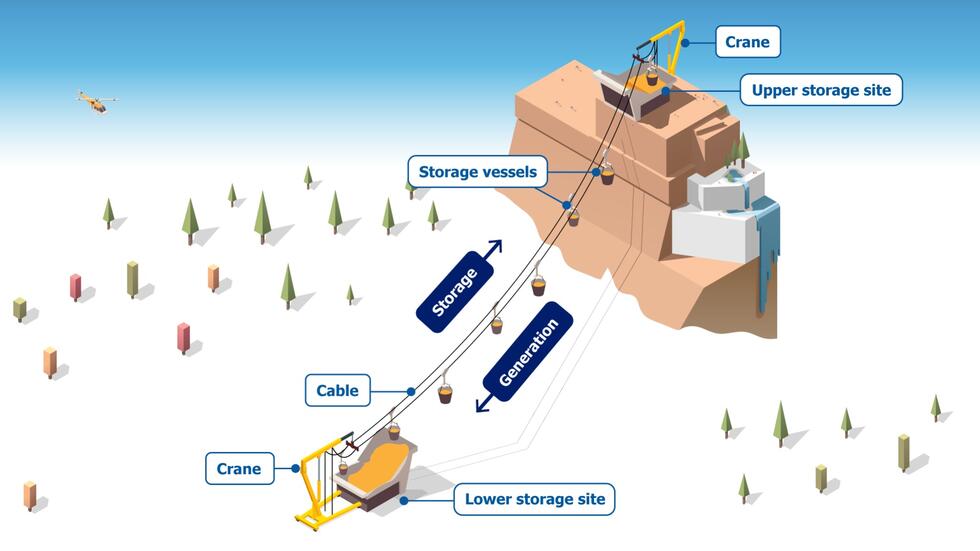

Almost five months of development work and 115 components went into Martin Fischer’s latest clock – the “Clockwork 2.00B”, a do-it-yourself kit with a limited production run of 200 units. The production of the clock parts and the pre-assembly take about two days. Fischer uses mild steel for the frame, the weight, and the anchor fork, brass for the cogs, leather for the winding strap, carbon for the pendulum rod, and CK45 steel for the escapement. The movement consists of just three cogs and one escapement wheel.

The weight (which stores the energy) drives the slowest cog – the hour wheel – via the winding mechanism. The rotation is transmitted via the intermediate cogs to the fastest wheel, the escapement wheel. This in turn drives the pendulum, which is connected to the anchor fork. Via the escapement, the swing of the pendulum causes the escapement wheel to stop and then continue moving. When the escapement wheel stops, the other cogs and thus the hour wheel, which moves the hour hand, also stop. In this way, the hand advances in a precisely coordinated cadence; the clock does not have a minute hand.

The “Clockwork 2.00B” costs 2,500 Swiss francs and must be assembled by the customer. Martin Fischer even offers his customers clock assembly workshops. www.clockwork.ch

Written by: Jan Graber

Photos: