SHORT NEWS

The dilemma of self-driving cars

What should one do in a deadlock situation, run over an elderly person or a young child? Such ethical dilemmas take center stage in the public debate relating to self-driving cars. However, there are other much more pressing questions.

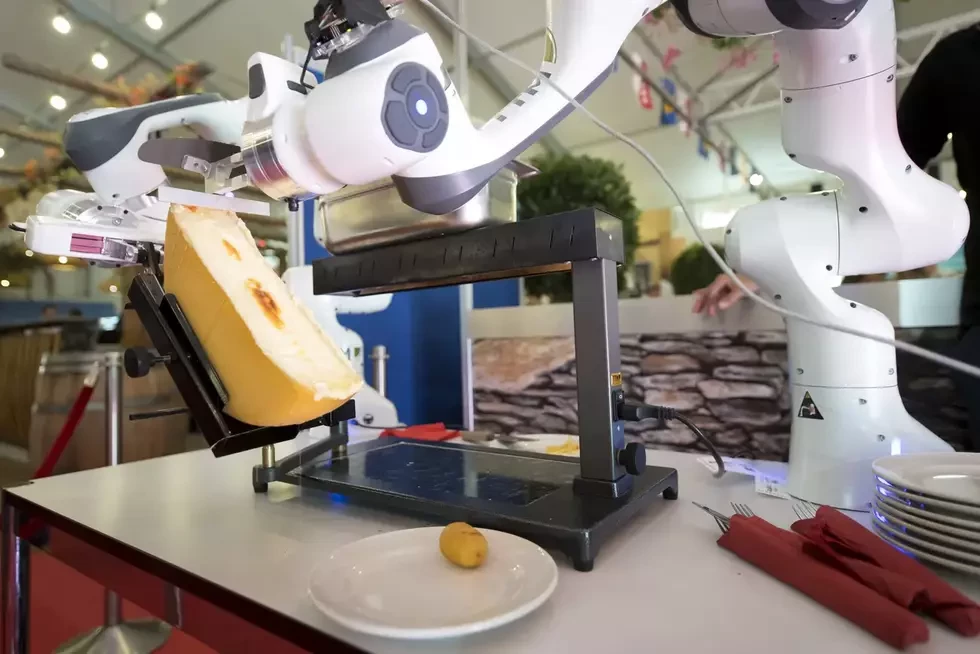

If technology and software take over the steering wheel, road traffic could become safer and more resource-friendly. Or alternatively, the traffic on the roads might even increase. The automation of mobility is advancing and raising questions about which the public discourse has yet to begin.

The TA-Swiss Foundation for Technology Assessment recently published a report that provides a basis for this public and political debate on the increasing automation of vehicles and their future role in Switzerland. In their report, the experts outline various possible developments in Switzerland based on a number of scenarios.

More convenience, more traffic

As previous studies in Switzerland and other countries indicate, a mainly market-driven development would probably lead to more traffic, the report states. Because then the focus would be on the individual utilization of vehicles: More and more people would purchase self-driving cars, which could even be on the roads without transporting any passengers at all.

Even people who do not have a driver’s license, for example children or elderly people who are no longer able to drive themselves, would be able to use them. What would be beneficial for the individual could significantly increase the level of traffic in Switzerland.

The scenario could be quite different if the government were to intervene more strongly to promote the collective use of self-driving cars in the form of “individualized public transport”. As a substitute for buses and cabs, self-driving vehicles could always be on call, more or less independent of fixed timetables. This would make owning a car unnecessary and the utilization of the vehicles would increase. This would reduce the traffic in cities, and the number of required parking spaces.

If the emphasis were to be placed on environmental sustainability, this would arguably be the more sensible option. However, it would mean a certain limitation of individual mobility.

The environment and safety versus freedom

This is precisely where a number of ethical questions arise, as Tobias Arnold from the consulting firm Interface, which was also involved in the report, says. To what extent should the government be permitted to intervene in individual mobility and freedom of choice in order to prioritize safety and an improved environment?

If all vehicles were self-driving, there would be no more accidents. At least none caused by human error. But should the government be permitted to dictate that individuals use automated vehicles because they are safer than conventional cars? And should government be permitted to force cyclists and pedestrians to integrate themselves into a networked transport system, which is the prerequisite for automation?

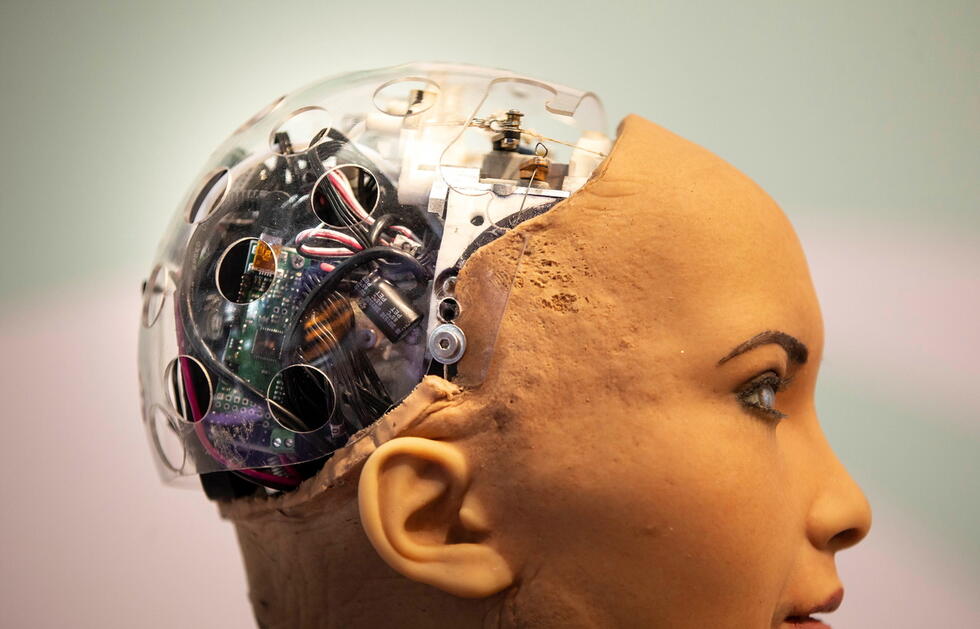

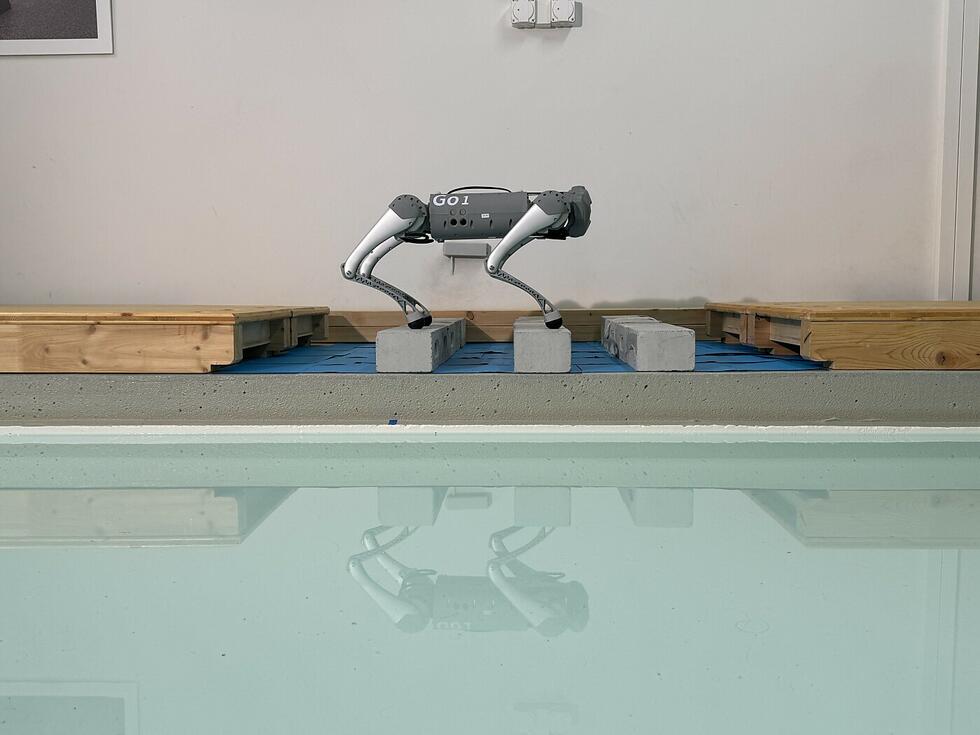

In order for self-driving cars to navigate the roads safely, particularly in cities, they must be networked not only with each other but also with other road users such as pedestrians and cyclists.

Predefined routes for all road users

Although built-in sensors can detect the vehicle’s surroundings, they only ever see the “now”, as Fabienne Perret from the consulting firm EBP said in an interview with the Keystone-SDA news agency. But to navigate safely, the vehicles must also anticipate the movements of other road users. Pedestrians and cyclists would thus have to indicate the route on which they intend to move and from which they would not be allowed to deviate. And they would have to wear transmitters that share this information.

To be able to nevertheless respond to spontaneous movements, the speed of self-propelled vehicles would have to be severely limited, at least in urban areas, Perret explained. Whether this type of mobility would still be sufficiently attractive is another question.