Will robots soon help care for the elderly?

There is already a chronic shortage of qualified staff in the nursing sector, and demographic change will only exacerbate this development. Consequently, a research team at the German Aerospace Center is developing robots for use in nursing homes.

The small one-room apartment could feature in a furniture catalog: Brightly colored plastic fruits lie on the kitchen counter, a photo of a juicy roast is attached to the oven door, a large television is mounted on the wall above a sideboard, and vis-a-vis is an angular sofa and a small cabinet. Only the wheelchair does not quite seem to fit into the setting. And yet, everything here was set up specifically because of it.

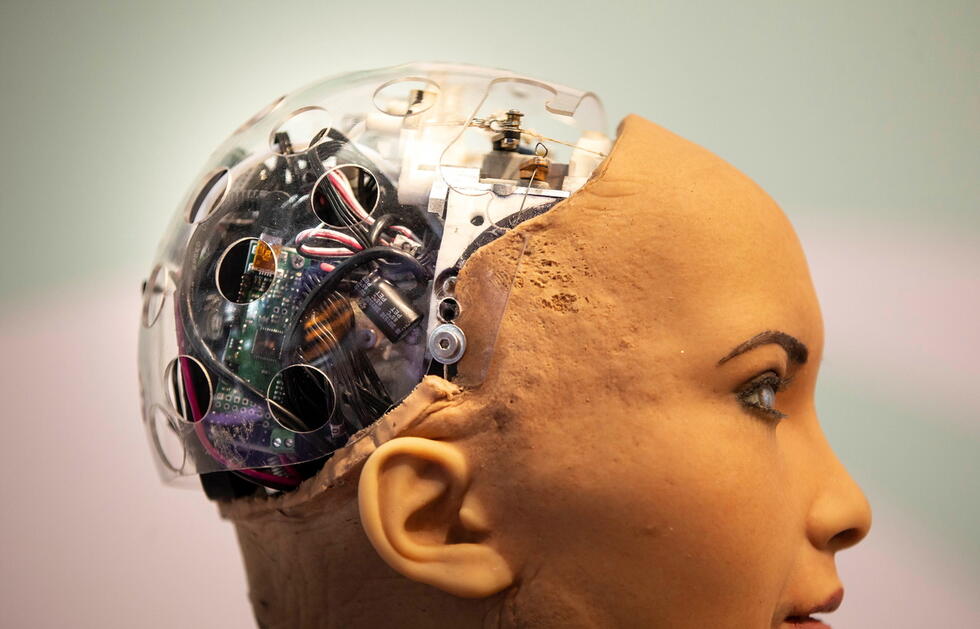

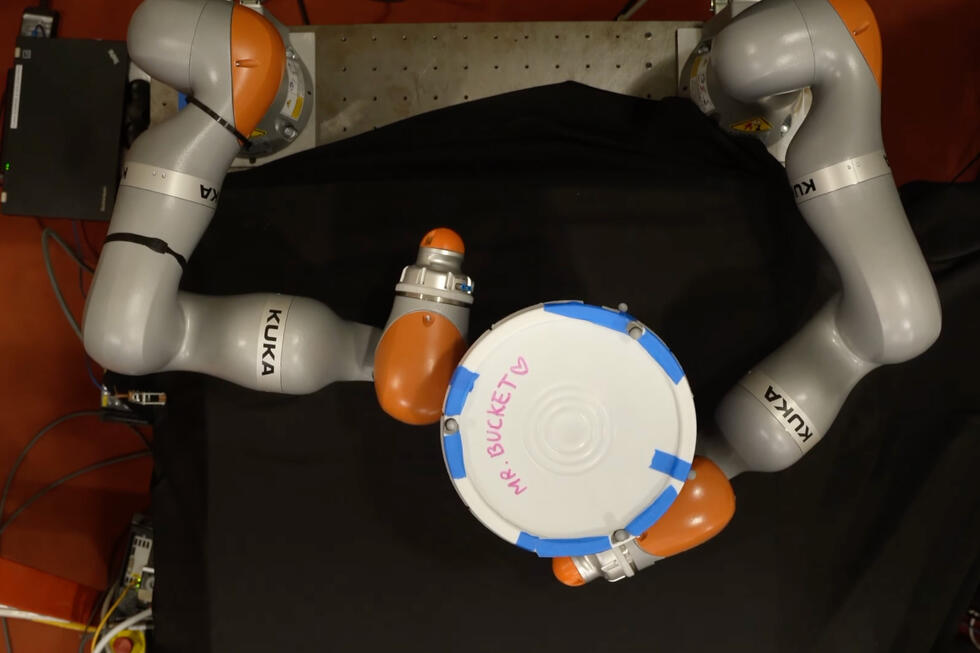

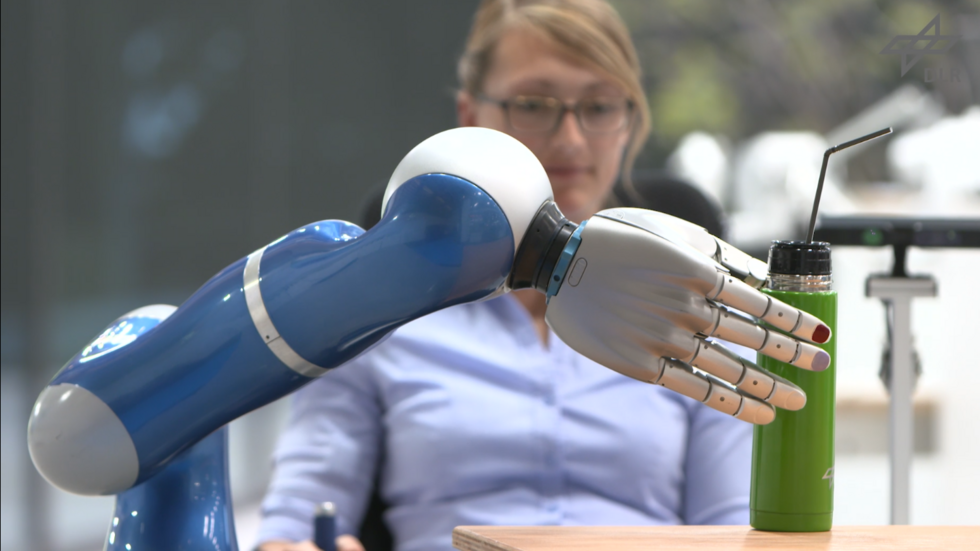

The one-room apartment is an experimental laboratory at the Institute of Robotics and Mechatronics of the German Aerospace Center (DLR). Here EDAN, the wheelchair, is learning how to function. It is being taught by Jörn Vogel and his team. Because EDAN is more than just a means of getting around, it is a “robotic research platform”. Crammed with electronics and an artificial intelligence computer system. Thanks to cameras and sensors attached to the headrest, EDAN can observe and interact with its environment. Or, as its developers put it, “manipulate” it. This is made possible by its blue-silver robotic arm equipped with a slender hand.

EDAN is more than just a means of getting around, it is a “robotic research platform”. Crammed with electronics and an artificial intelligence computer system.

The intelligent wheelchair is controlled using an electromyograph (EMG), which measures muscle signals. There are diseases such as spinal muscular atrophy that cause paralysis of the entire body. However, the brain continues to send signals to the muscles, which can be measured using the EMG and converted into movements by EDAN. EDAN (EMG-controlled daily assistant) is designed for people with motor impairments. However, it can also be maneuvered using a joystick or a tablet that is normally attached to the armrest.

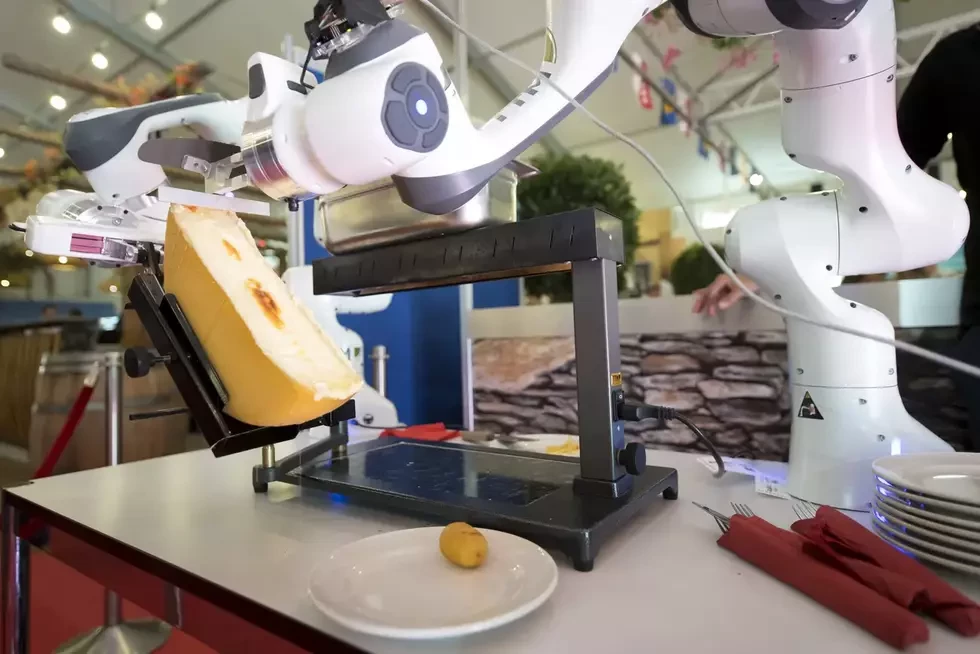

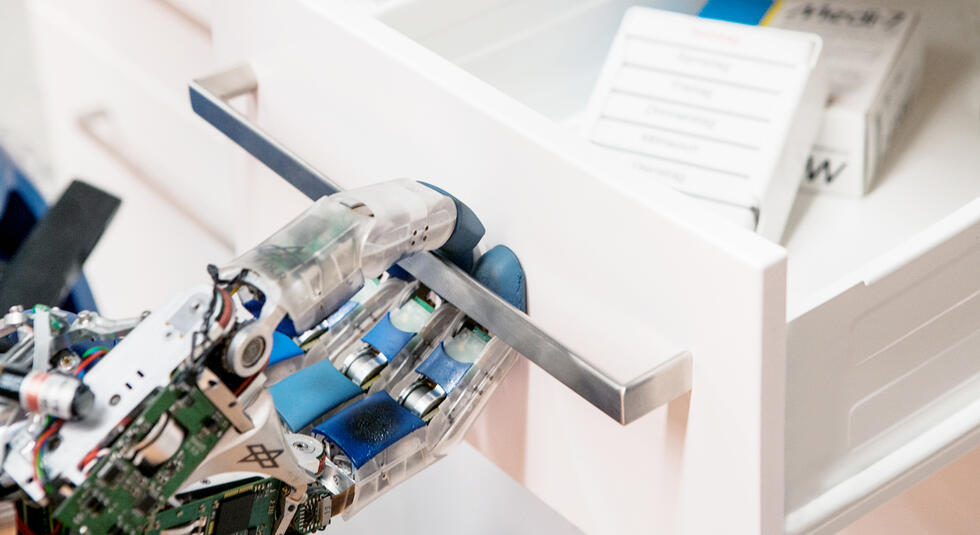

Now, however, it is in the hands of Jörn Vogel. He wants to demonstrate what EDAN is capable of and taps on the screen. The tablet displays EDAN’s camera perspective on the laboratory apartment, in its focus: the cabinet. Vogel selects the “power grip” function. From here on the wheelchair knows what it has to do. The cabinet’s top drawer is highlighted in green. The wheelchair moves, corrects its direction, and approaches its destination. Its robotic arm moves upwards – its movements exude elegance. This is made possible by seven joints with torque sensors that enable very precise positioning. EDAN carefully puts its rubberized fingertips on the drawer handle. However, it does not grasp it like a human would. It simply applies a gentle pressure and slowly withdraws. The drawer opens to reveal a plastic banana.

Jörn Vogel’s robots can help

With some 2000 researchers, the DLR facility in Oberpfaffenhofen near Munich is one of the largest research centers in the German-speaking world. Here, Jörn Vogel is in charge of the SMiLE project: “Service robotics for people in life situations with impairments”. EDAN is intended to perform everyday tasks, such as closing a window or pouring a glass of water, for people who can no longer move due to illness or old age.

And not only in private homes: “In a few years’ time, our robots will be able to support staff and residents in inpatient care facilities,” Jörn Vogel emphasizes. The 37-year-old stands next to EDAN in the living room laboratory, which is surrounded by monitors and whiteboards, with thick cable runs stretching across the floor. He grins – he is in his element. He comes across as a friendly, engaging person and is one of those researchers who are able to put their enthusiasm for their own field into words. For example: “We want our robotics systems to give people back a measure of independence.” Or: “Our previous experiments were a tremendous experience for me.”

We want our robotics systems to give people back a measure of independence

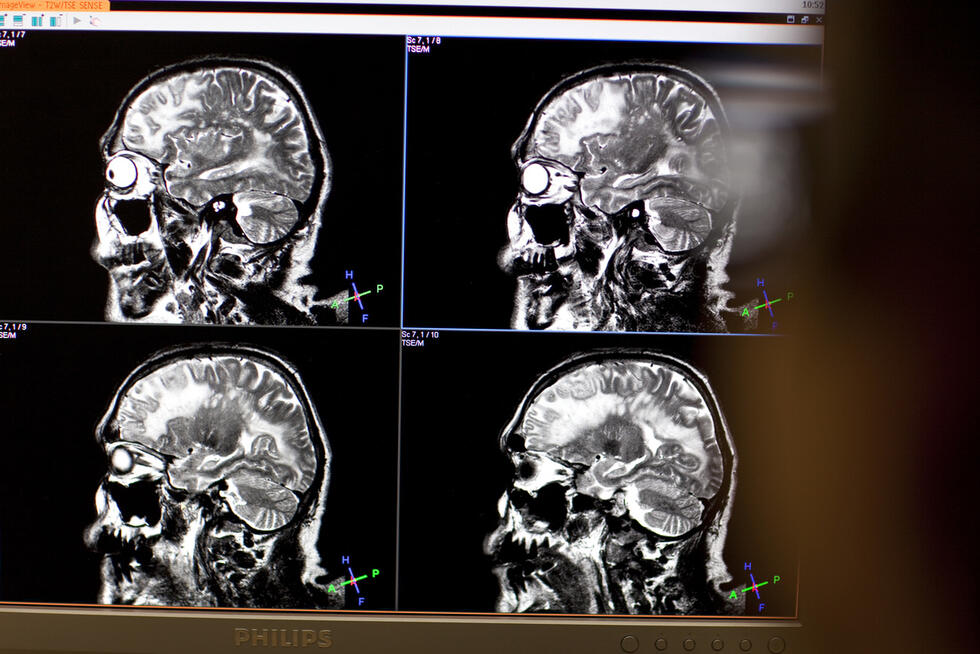

Already in 2012 Jörn Vogel witnessed how robots can help people. At that time he was involved in an experiment that was subsequently published in the “Nature” journal: An interface was implanted in the brain of a test subject. The implant responded to her thoughts and transmitted commands to a robotic arm. A modified version of this interface is now used in EDAN. The controls were rudimentary: The only commands the test subject, Cathy Hudginson, was able to give via the brain-computer interface were “forwards”, “backwards”, “left”, “right”, “reach”, “lift, and “tilt”.

Nevertheless, the implant enabled the paraplegic woman to drink from a cup without human assistance. “It was the first time in 15 years that she was able to drink without someone else’s help. Whenever she was thirsty, she always had to wait until someone asked her. Following a stroke, she is no longer able to speak,” Jörn Vogel explains.

Specialists from different disciplines work together to “close the loop”

Jörn Vogel does not want his robots to replace nursing staff. Quite the contrary: The goal is to reduce the burden on caregivers to improve the quality of their work. “You cannot replace human care. A robot simply lacks the empathy,” Jörn Vogel says. But if a mug is dropped, the robot arm could clear it up and wipe up the spill. But only if somebody tells it to do so. EDAN’s role is to assist, not to drive around and independently search for things to do.

You cannot replace human care. A robot simply lacks the empathy!

SMiLE was born out of assistant robots designed for space travel. Originally the task of the robots – in addition to EDAN, the DLR is also researching other systems – was to support astronauts in space. Later it became clear that they could contribute a great deal to transform a second sector: patient care. Many European countries are experiencing a shortage of qualified care professionals, and many vacancies remain unfilled. The figure in Germany is estimated to be as high as 80,000. Projections suggest that 15 years from now there could be a shortage of between 150,000 to 300,000 care personnel.

Because the engineer Jörn Vogel and his team are not sufficiently familiar with daily nursing routines, SMiLE brings together experts from the fields of robotics, nursing ethics, nursing studies, and nursing documentation: What are the ethical prerequisites for the work with physically handicapped people? Which tasks can be performed by robots? Mid-year, the laboratory phase is scheduled to move from Oberpfaffenhofen to a real nursing environment of the Caritas association in Garmisch-Partenkirchen. This is where the people requiring care, care workers, and robots come together.

“Closing the loop” is what Jörn Vogel calls this step. What most people know about robots comes only from movies and television. In this real-life environment, he wants to demonstrate what they are actually capable of doing and what not. “In return, we are interested in what kind of help caregivers might want and what services those in need of care would appreciate,” Jörn Vogel explains. His goal in Garmisch-Partenkirchen is not to test his system, but to “identify realistic application scenarios”, which he will develop further in a later phase. He hopes that caregivers and residents will come up with the best ideas in their familiar surroundings.

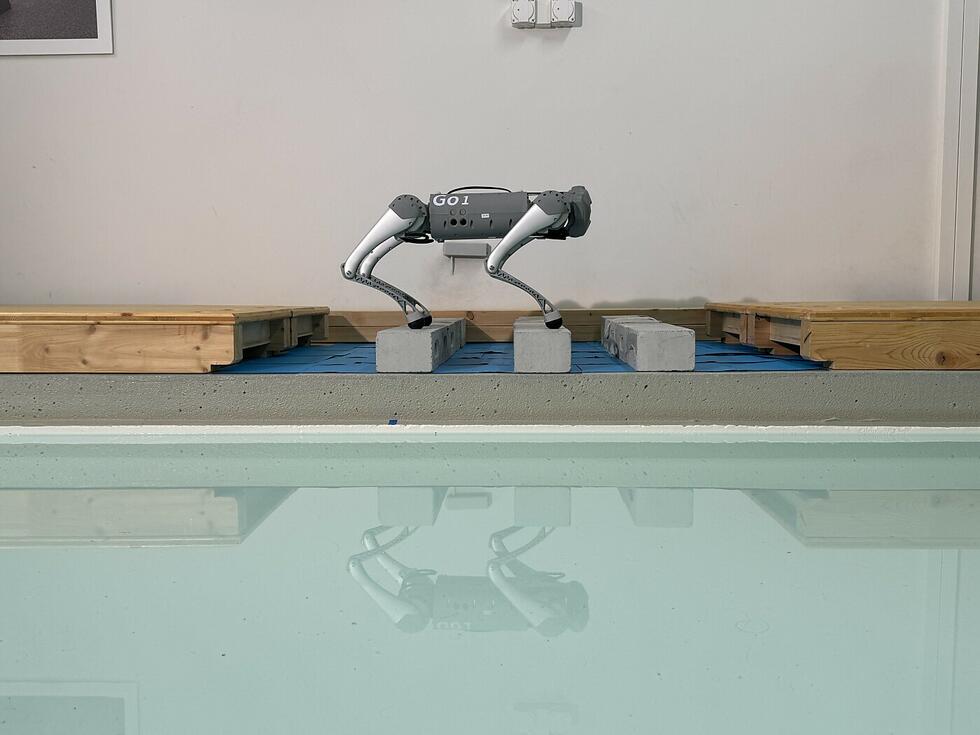

Variation is the challenge

EDAN’s robotic arm learns to move through human guidance. Jörn Vogel initiates the learning mode by selecting the “arm manual” setting on the tablet: This allows the arm, which is smooth and surprisingly warm and which vibrates gently due to the electrical system and motors inside, to be guided. Jörn Vogel seizes it and stretches, bends, and twists it into constantly new positions, curving its fingers or leaving the hand suspended in the air. In this way – in something akin to a dance with its engineer – EDAN practices wiping, grasping, “manipulating”. This is also how it learned to open a drawer or hold a mug.

The idea is for the robots to “understand” that they should not only pick up a dropped glass, but also wipe up the spill

“The greatest challenge is to deal with variation,” Jörn Vogel explains. “Our system is currently learning to interpret its sensor data and draw the right conclusions. We do not want to model every object in the room individually, but rather to teach EDAN to draw conclusions from one specific cup, which it can then apply to many different cups.” The idea is for the robots to “understand” that they should not only pick up a dropped glass, but also wipe up the spill. Programming this partial autonomy to be reliable and robust – i.e. not susceptible to errors – is the most difficult step.

Precautionary approach to research

In the laboratory EDAN is permitted to make mistakes, drop objects. Later, it must navigate without accidents, even in unfamiliar environments. Under no circumstances must it pose a danger to people in care facilities. Thanks to its highly sensitive sensors, EDAN has the required technical prerequisites. This has already been demonstrated during a parallelproject: EDAN’s robotic system is also being researched for use in surgery to assist with minimally invasive procedures. During one experiment, the robotic hand guided a scalpel towards a pig skin. Before the blade penetrated the skin, the system detected the contact. No cut, no injury. “That’s how finely it can be tuned,” Jörn Vogel emphasizes. “Safety is paramount. Whenever it interacts with people, we apply the precautionary principle and always have a finger hovering over the emergency stop button.”

The exciting thing about EDAN is that it doesn’t do anything without receiving an external command. Over the next few years we will therefore learn a great deal more about how people behave with the system and how they use it.

The SMiLE project is scheduled to run for another four and a half years. This is the period for which the funding is secured by the Bavarian Ministry of Economics and the DLR: with 4.5 million euro. By then Jörg Vogel hopes that EDAN will have learned many new application scenarios. Even if these only become concrete during the interaction with test persons. When they are “in the loop”, as Jörg Vogel dubs this process. “The exciting thing about EDAN is that it doesn’t do anything without receiving an external command. Over the next few years we will therefore learn a great deal more about how people behave with the system and how they use it. Maybe they will use it entirely differently than we programmed it.”

Written by:

Illustration: Liebana Goñi