Scrubbers with an artificial brain

Artificial Intelligence makes robots mobile and autonomous. This is of particular interest for the manufacturers of cleaning equipment and their clients: Several 10.000 cleaning robots are currently deployed – and because of Corona, the number of smart cleaning machines is growing.

Cleaning and sweeping are not considered to be intellectually stimulating. But if the current Covid-19 pandemic has accomplished anything, it is bringing new respect for these seemingly simple, often monotonous, but literally vital cleaning tasks. Human cleaning crews are increasingly supported by robots doing the dirty and gritty work, and thereby freeing up capacities for the more sensible tasks of cleaning and disinfecting delicate and complex surfaces. And those robots display quite a bit of intelligence – Artificial Intelligence, that is.

AI doesn’t get bored as easily as the human brain, when occupied with monotonous tasks like sweeping floors. And this insight inspired Dr. Eugene Izhikevich, a Russian-American neuroscientist and at the time Professor for Computational Neuroscience (a fairly new discipline) at the Neurosciences Institute in San Diego: Eleven years ago, he left academia and started his own company, Brain Corp, in San Diego, with the purpose to develop operating systems for autonomous mobile robots (AMR). “His goal for Brain Corp was to become the Microsoft of robotic systems”, explains Michel Sprujit, Vice President and General Manager Europe at Brain Corp, when I talked to him via Zoom, speaking without any pretense of modesty.

His goal for Brain Corp was to become the Microsoft of robotic systems

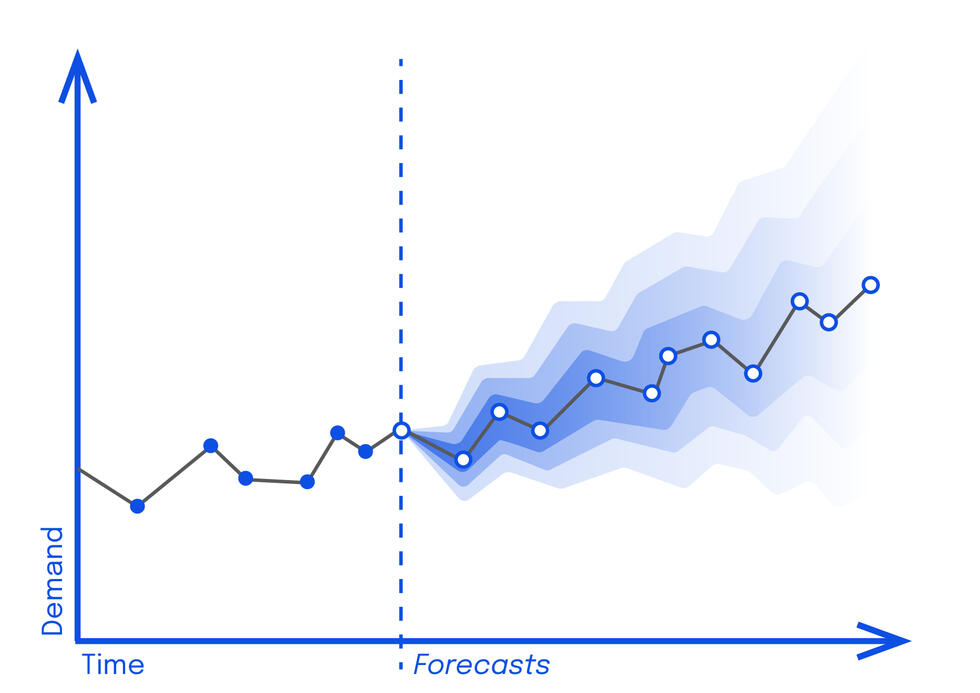

It was no coincidence that Brain Corp focused on autonomous cleaning robots: For one, small autonomous carpet cleaners like iRobot’s Roomba had become popular and thereby paved the way for a broader deployment of autonomous cleaning appliances. And at the same time, manufacturers of floor care equipment – namely companies like Tennant, Nilfisk, and ICE Robotics – and their customers, primarily large retail chains in the US, like Walmart and Kroger, became increasingly interested in the potential for smart cleaning robots: An industry study projected an annual demand of nearly 300.000 AMRs by the year 2030. And the current pandemic, with its heightened demand for hygiene, has helped drive this demand even faster.

“We had been looking for platforms to use BrainOS for robots. But we wanted to focus on one thing first, and cleaning robots happened to be the most promising”, Sprujit. These robots fundamentally rely on the same sensors as self-driving cars: 3D cameras and LIDAR sensors. But other than cars, cleaning robots operate in an environment that can be planned and controlled, and that AI can quickly learn. And at best, they move at the speed of pedestrians, which minimizes the risk for severe accidents.

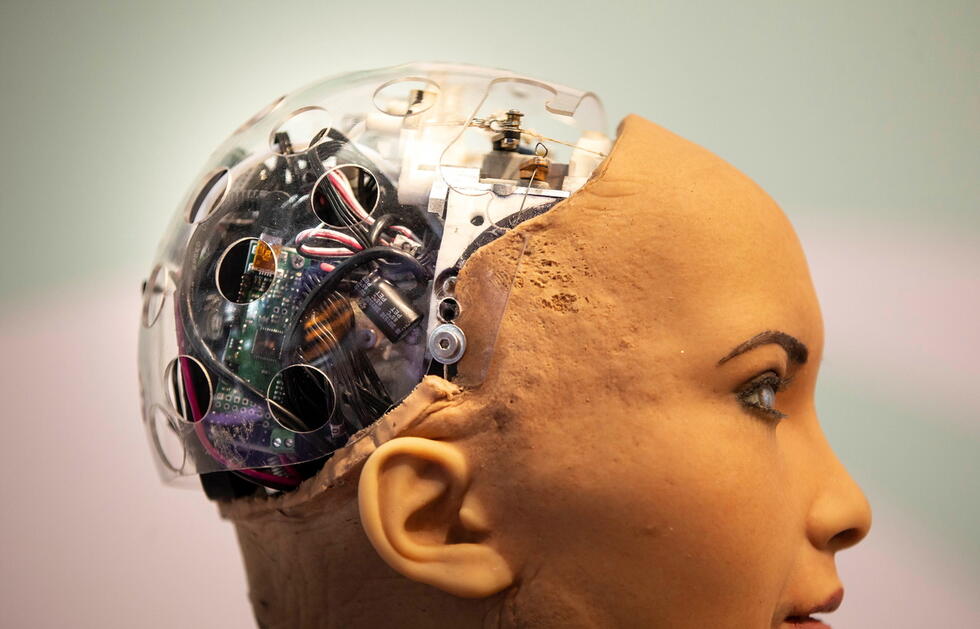

Mimicking the nature of the brain

Before he began putting Artificial Intelligence into cleaning machines, Izhikevich made a name for himself as a leading expert on Spiking Neuronal Networks (SNN). The idea behind this network architecture is to mimic the biological functions of neurons in actual brains by modulating electrical impulses – unlike the so-called Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN), which can be compared, in principle, to a multi-layered resolution matrix where each layer is fairly simple. These SNN “nervous systems”, inspired by biology, are computationally far more complex than CNNs, which makes them less popular for AI research. Izhikevich has a Master of Science degree in Applied Mathematics from Lomonosov Moscow State University and earned a Ph.D. in Mathematics from Michigan State University; in 2005, he created what was then considered the most complex neuronal model in the world: With one hundred billion artificial neurons and one quadrillion synapses, it approximated the human brain.

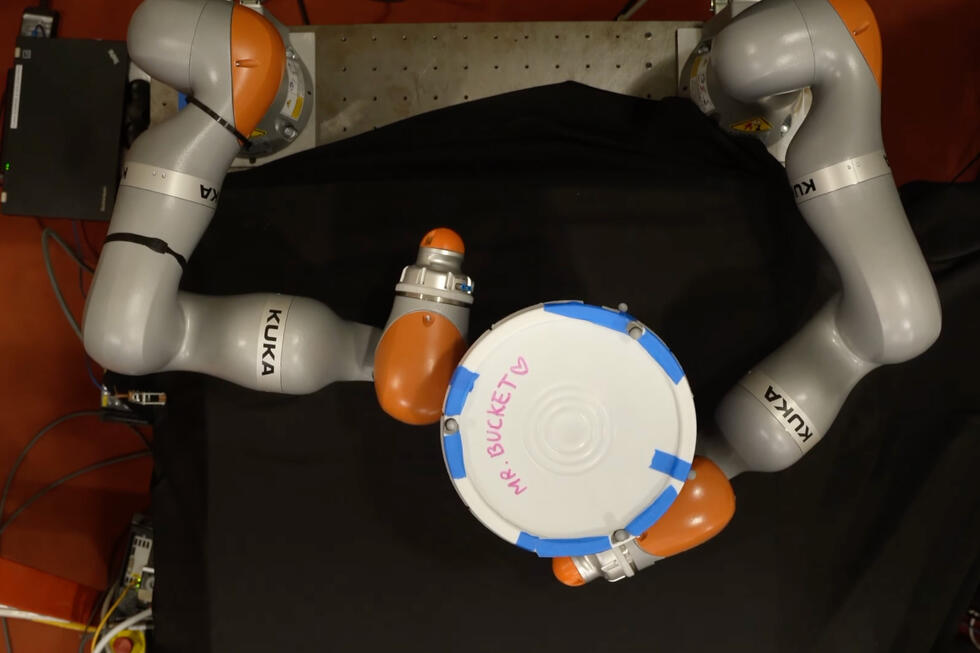

Izhikevich hatched the idea that led to Brain Corp’s foundation together with his colleague Dr. Allen Gruber, who was a professor for Neuroscience at the University of California at the time. Their business idea was to develop an operating system for robots that, unlike the industry standard at the time, was not proprietary to any specific model or manufacturer. And Brain Corp immediately began to cooperate with hardware manufacturers, rather than building its own robots: For its first five years, the company was run as an incubator under the umbrella of the computer chip and mobile phone manufacturer Qualcomm; since 2014, Brain Corp stands on its own, with Izhikevich as CEO and Gruber sitting on the Board of Directors.

The first commercial cleaning robot running the BrainOS operating system was introduced in 2016; this was collaboration with the manufacturer Intelligent Cleaning Equipment (ICE) and lovingly named EMMA, which is short for Enabling Mobile Machine Automation. This cooperation evolved into a venture called ICE Robotics, which became a stand-alone brand under the roof of the Japanese robotics corporation Softbanks Robotics in 2019. The US cleaning equipment manufacturer Tennant followed up in 2018 with its first BrainOS-powered cleaning robot; their competitor Nilfisk introduced its first Model in 2020. The German cleaning equipment manufacturer Kaercher is listed as a Brain Corp partner, but is not yet offering robotic floor scrubbers or sweepers.

By early 2020, more than 10.000 autonomous BrainOS floor cleaners had been deployed globally; then Covid-19 happened, and the demand exploded: By mid-2020, the fleet size had increased to more than 14.000, according to Josh Baylin, Senior Director of Strategy at Brain Corp, who discussed the effect of Covid on the company’s business in a podcast. And these machines operated at 12 percent higher capacity than just a year before: “The pandemic has made retailers recognize how valuable robots can be in day-to-day operations: Cleaning has become a mission-critical task.” And the more conspicuous this cleaning process happens, the better.

Ten minutes for programming

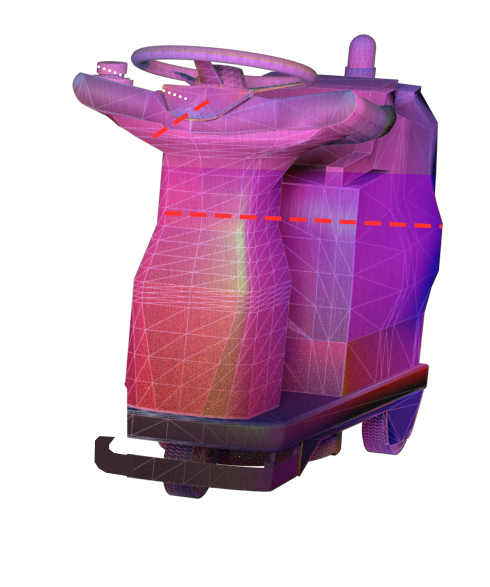

All these robots have one thing in common: At first glance, they are indistinguishable from a conventional ride-on floor cleaning machine, with a driver seat and a steering wheel. One has to take a closer look to notice the optical sensors; the most auspicious indicator for the robotic nature of the machines is the BrainOS logo displayed on the front – and, of course, the fact that these machines autonomously navigate the aisles and halls of supermarkets, shopping malls, and airports, where they are mainly deployed – without any human intervention. Or rather: Almost without human intervention.

The BrainOS software relies on the principles of “teach and repeat”, as Michel Spruijt explains: “All you need to program a route is to have a person drive it once – it takes less that ten minutes for the machine to learn and to be able to consistently repeat a route.” Unlike driverless transportation platforms that are already in used in industrial warehouses and on factory floors, BrainOS-powered robots do not need specific floor tracking markers to find their way. And thanks to AI, they can do more than just recall a nearly unlimited number of pathways through their area of deployment: They can also negotiate unexpected obstacles – especially ones that are moving, like customers and their shopping carts. When the sensors pick up on such an obstacle, the software makes an estimation how and where the obstacle will move. The robot will then either wait for the path to be cleared, or carefully maneuver around the roadblock.

It takes less that ten minutes for the machine to learn and to be able to consistently repeat a route

But what if there is no way to avoid the obstacle? In that case, the robot will call for help, using the built-in 4G cellular connection to send a message to the smartphone of a human employee. According to Spruijt, this happens on average once every hour, but typically can be resolved is easily. He points out that the aim is not to replace humans, but to free up their time and effort for more important tasks – like cleaning surfaces which are beyond the reach of the floor sweepers. And that is what matters during the pandemic: “Two out of three people are afraid to go back to grocery shopping for fear of infection. They want to see that the place is being cleaned.”

Cleaning robots contribute to this reassurance in two ways: For one, they can “mingle” and do their job – quite visibly – in the busy daytime, rather than scrubbing the empty markets and airports during the nighttime. And they can also provide relief to the cleaning crews that are currently quite overwhelmed with the task to keep every potential contact surface clean: Just in the first nine months of the pandemic, the time that employees no longer had to spend with monotonous, but time-intensive floor scrubbing and thus became available for more complicated disinfection tasks added up to almost three million work hours. Or, as Spruijt calls it, “we do the heavy lifting”.

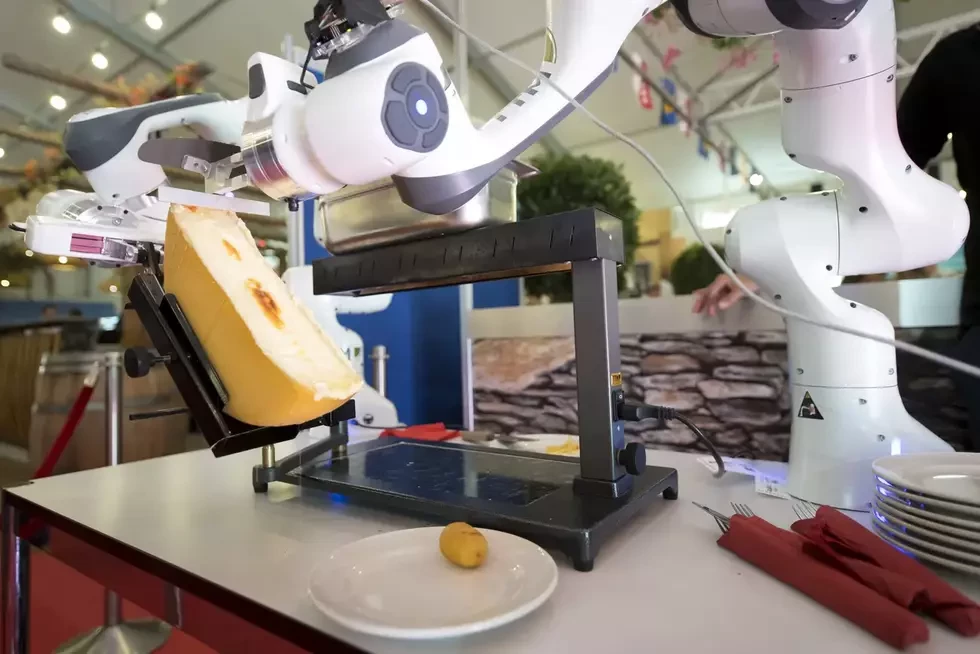

And not only that. The BrainOS operating system is capable of more than retracing cleaning routes: Brain Corp is currently working on robots that are capable of detecting if shelves need to be re-stocked. Cameras can scan every foot of shelve space in a supermarket and upload the images for processing to a cloud service, using the 4G mobile phone connection, which is already used to record any incident and every new route for the cleaning robots. Other mobile platforms use BrainOS to transport groceries from storage to the shopping floor, and may soon be able to deliver pre-ordered and prepaid grocery baskets to customers waiting outside the supermarket. The point is to reduce interpersonal contact and by doing so, reducing the risk of spreading the contagion.

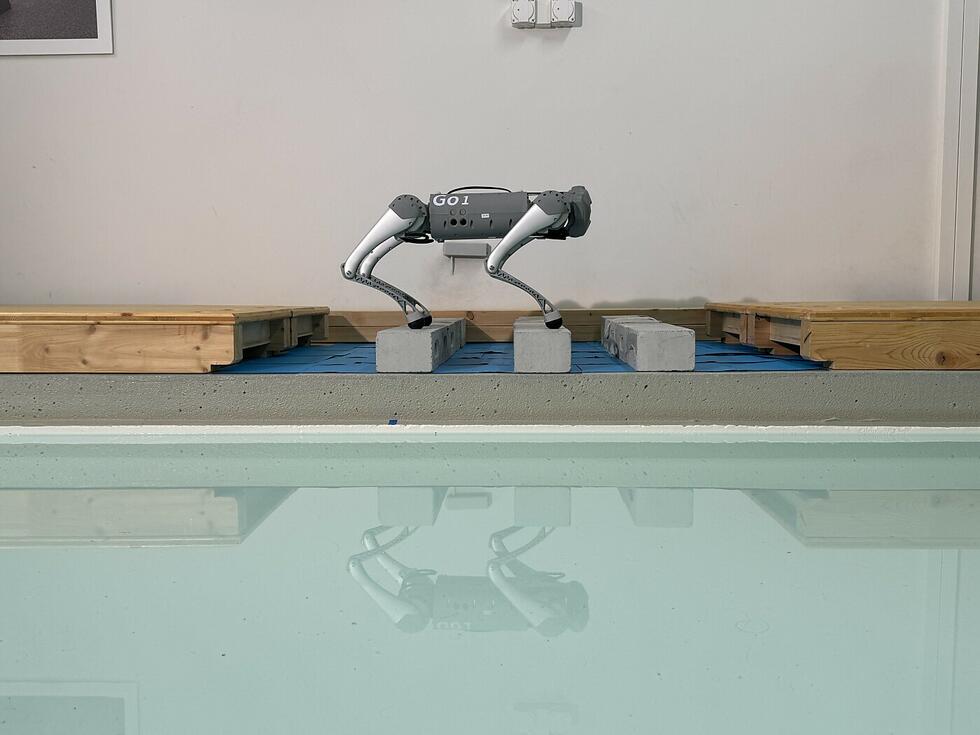

Smart cleaning robots at work

Compliant with data protection regulations

And although Spruijt does nor explicitly specify this, BrainOS equipment comes with an extra potential: It records all the environmental imagery that the robots create – each robot can store up to 100 Gigabytes for video and another 50 Gigabytes for data, which makes it into a mobile surveillance camera. When it reaches its storage capacity the operating system overwrites old data, but important events and data can be permanently stored in the cloud – just like with typical camera surveillance systems. “We are fully compliant with the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation”, assures Spruijt. Only data that is needed to improve the system would be stored, he explains. And every six to eight weeks, on average, the Operating System is being updated and upgraded, using the 4G data link.

This data service comes at a cost: While the BrainOS software is included in the purchase price of the robots, the software requires buying a subscription. The initial license is good for three years, but once that expires, customers have to buy renewals for either two or three more years, if they want to keep using the equipment. And what if a customer refuses to pay for license extensions? Would it be possible to “hack” the robot’s brain and run a generic operating system? “Our equipment is not compatible with other operating systems”, explains Spruijt, which brings to mind his initial analogy to Microsoft. A clever hacker might be able to fumble with the system – but then, the equipment would no longer run as desired. “Without a software license subscription, the robot is just an ordinary manual scrubber. We provide the brain.”

Written by: Jürgen Schönstein

Illustration: Justin Wood