AI with EQ

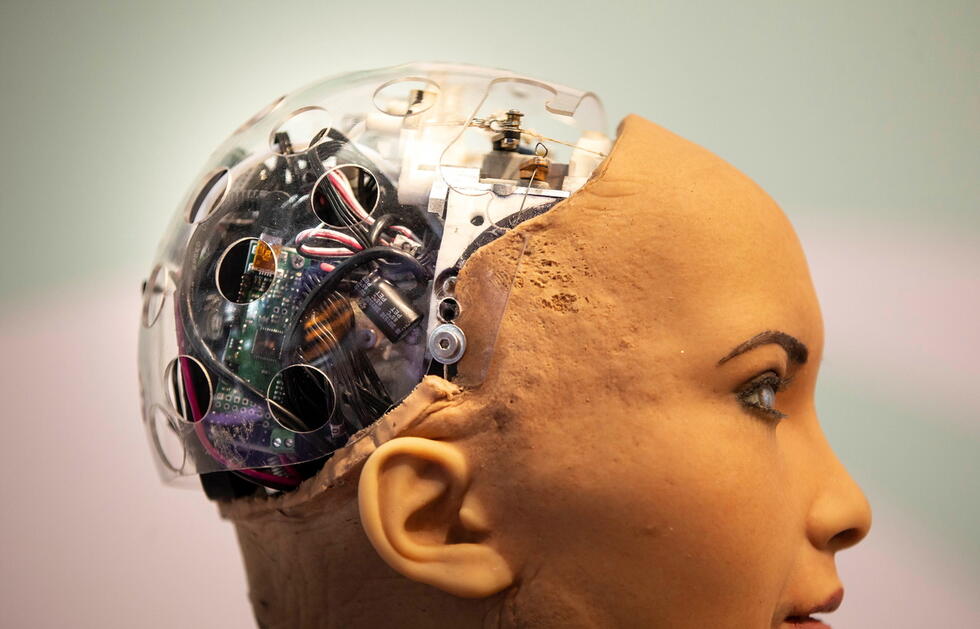

They are constantly becoming more sophisticated: Robots that recognize or simulate human emotions. What are they used for, and how do these systems work? A peek inside two research labs.

Machines that behave like humans, that are jealous, offended, or happy – Hollywood has been featuring them for decades. In reality, the development of emotional robots is only just picking up speed. “Endowing systems with emotionality and personality is one of the major current research topics in the field of artificial intelligence,” says Björn Schuller, a computer science professor at the University of Augsburg and Imperial College London.

Nowadays, however, whenever the talk turns to “emotional AI”, people are usually referring to emotion recognition systems; empathic AI, so to speak. “This is where the main focus is at the moment,” Björn Schuller explains. The reason: There is a very wide range of potential applications for emotion recognition systems. Björn Schuller: “Such algorithms fundamentally improve the communication between humans and machines.” For example, they can even detect cynicism or irony.

Already deployed in market research

So it comes as no surprise that a number of industries are interested in emotion recognition and that the systems are increasingly reaching the realm of robust applicability. The technology is already in use in market research. There, emotionally competent algorithms evaluate call center conversations or observe test subjects while they watch TV commercials. The buzzword: implicit tagging.

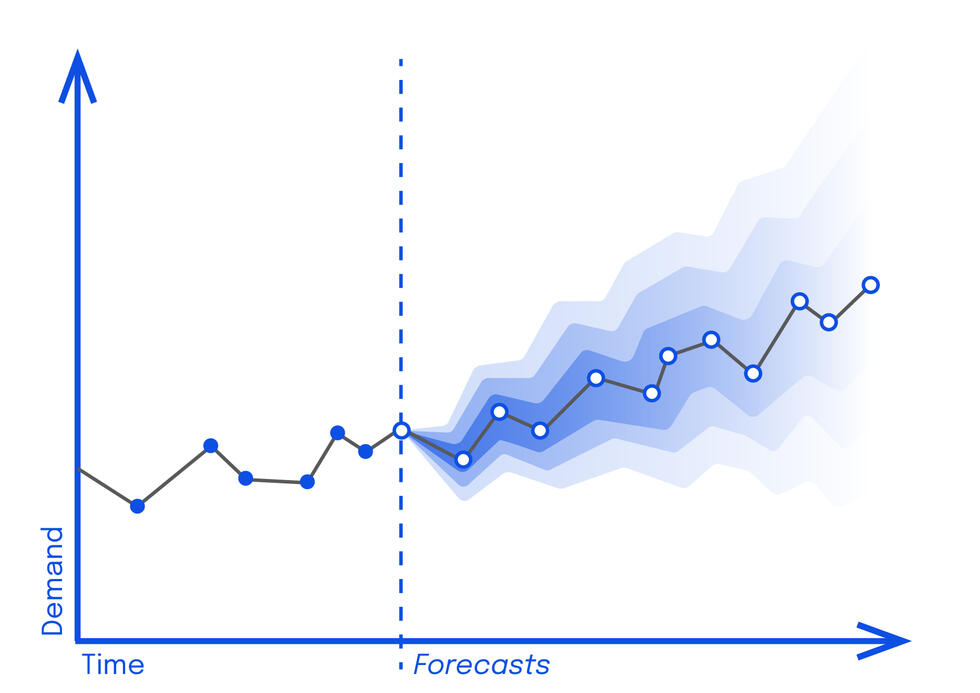

Other areas of application for emotional AI include safety and education: In the future, these systems will be able to detect aggression in public spaces, fatigue while driving, or overtaxing and boredom in the classroom. And the technology is also increasingly finding its way into our personal devices. The US market research and consulting firm Gartner expects that by the end of 2022, ten percent of smartphones, PCs, and tablets will be equipped with emotional AI to enable them to understand us better and make our lives easier.

“For this, we developed games that teach children to express different emotions, with a robot that awards them points for doing so.”

Autism therapy and depression detection

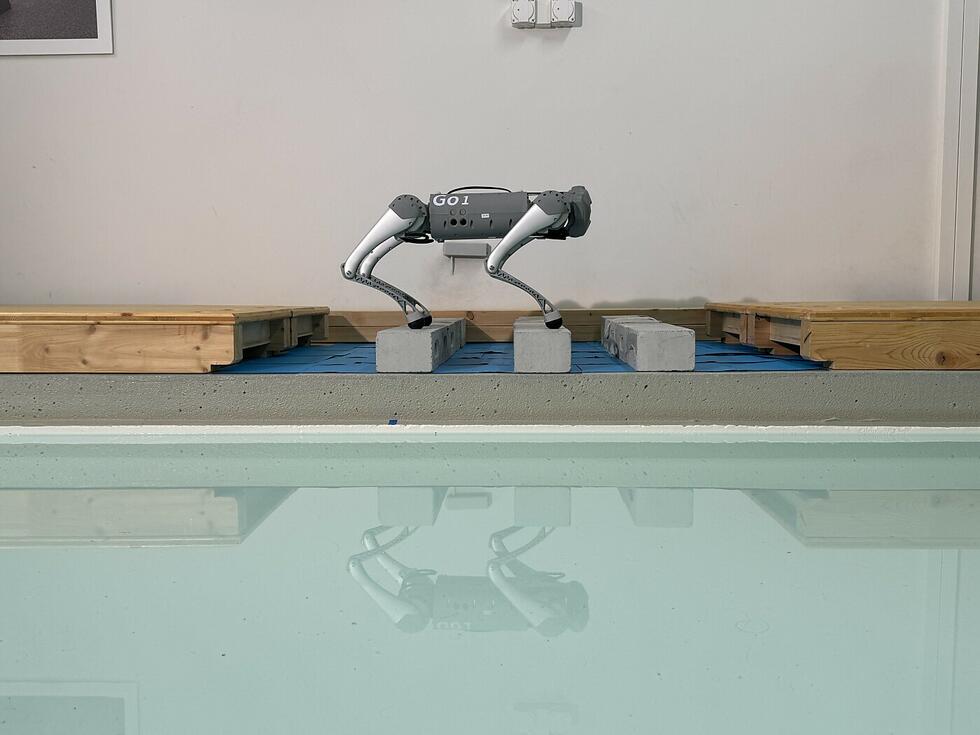

Björn Schuller wants to improve people’s lives. At the University of Augsburg, the Professor for Embedded Intelligence for Healthcare and Wellbeing is working on emotionally competent systems for medical applications. For example, for autism therapy. AI can help people suffering from autism to understand their fellow human beings. “For instance, in the form of a smartwatch that vibrates when a remark of a person they are talking to is meant ironically,” Björn Schuller explains. Other systems can help autistic children express their emotions. “For this, we developed games that teach children to express different emotions, with a robot that awards them points for doing so.”

Naturally: This feedback could also be provided by a human being. “But people with autism usually have a high affinity towards technology and enjoy interacting with robots,” Björn Schuller says. And there’s another type of patient who values artificial companions: People suffering from depression. Björn Schuller: “Frequently, people suffering from depression are much more likely to open up to an AI than to a human psychiatrist. They feel more at ease.” As a result, depression screening is the other main field of activity for the AI specialist.

Emotion recognition: These are the different types

Machines recognize human emotions using a variety of methods. Here are the most important approaches:

Machine vision – Algorithms detect emotions that are expressed visually. They interpret even the most subtle facial expressions – micro expressions –, body movements, and posture.

Speech analysis – Recognition of emotions using audible signals: The systems analyze tone, tempo, intensity, or modulation of the voice (for example within the context of the projects at the University of Augsburg). Or the emotion recognition functions linguistically: based on the content of written or spoken text.

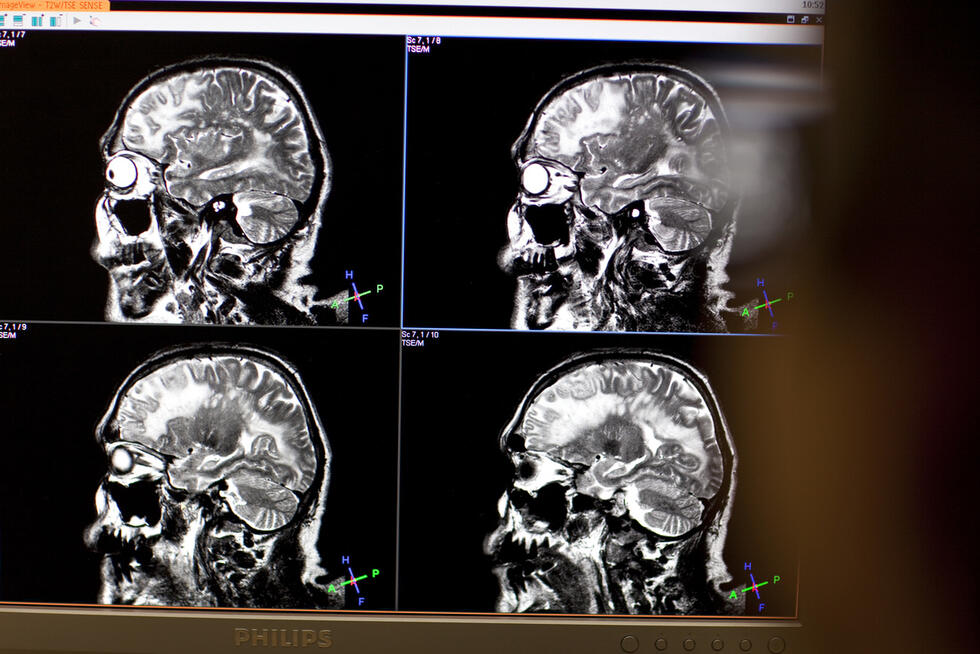

Physiological evaluation – Sensors measure pulse, body temperature, or skin conductance and use these values to derive emotions. Computer interfaces, for example, do this directly on the basis of brain waves.

The methods used by the algorithms to learn emotions are as varied as the types of recognition: In addition to supervised, unsupervised, and reinforcement learning, self-supervised learning is growing in popularity. “Self-supervised learning is all the rage right now,” the computer science professor Björn Schuller says. “It involves the systems using neural networks to first learn a fairly simple similar task. They can then use their findings to solve more difficult related tasks.”

A robot with feelings of its own

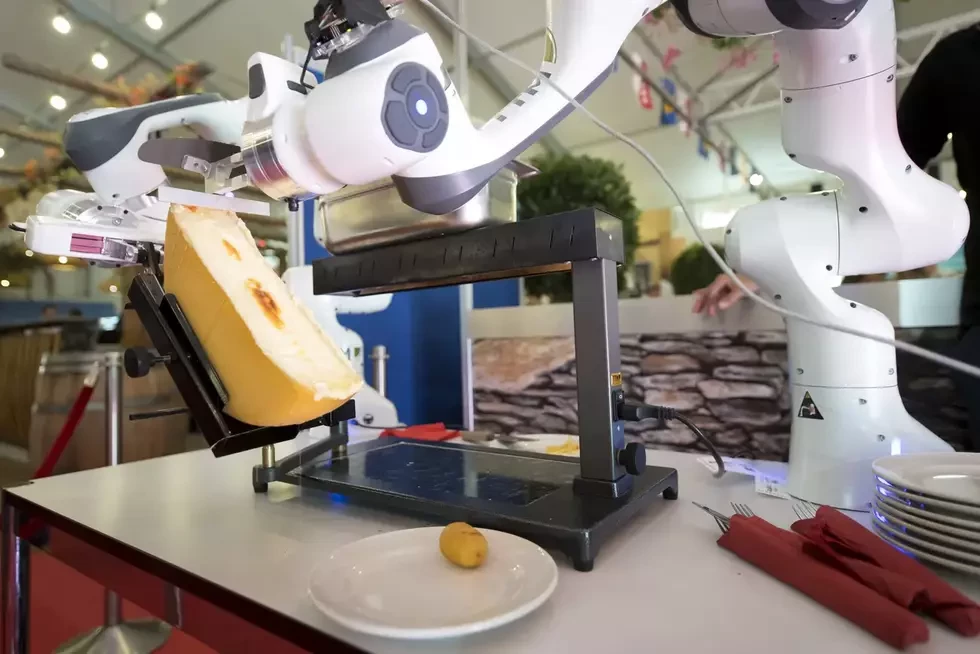

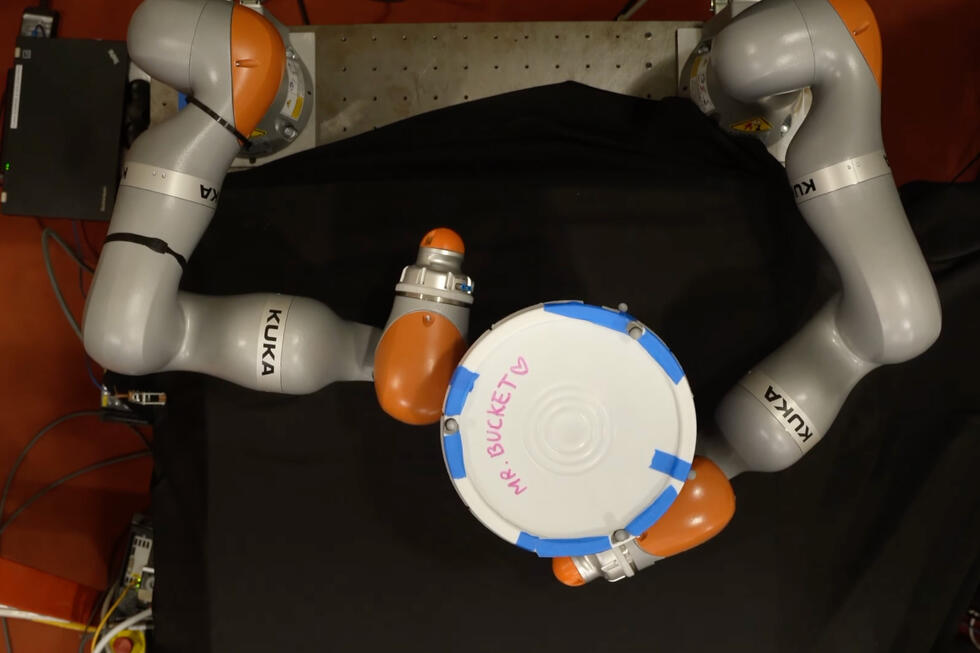

Change of location: 300 kilometers southwest of Augsburg, at the new Center for AI Research at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH) in Zurich. Here, Benjamin Grewe is taking things a step further. The Associate Professor for Neuroinformatics is developing AIs that exhibit what can be viewed as feelings of their own. He says: “Systems that are not only cognitively intelligent but also emotionally intelligent can solve complex tasks more effectively,” the neuro computer scientist explains. One of his AIs is capable of “feeling” fear. In the future, it could be used, for example, to develop a surgical robot. “Fear will drive the robot to work more cautiously, and it will thus be safer than conventional systems.” Benjamin Grewe sees applications for his AI in all areas where robots pose a risk of causing injury. “In medicine, but also in industry, where humans and robots are increasingly sharing workspaces.”

The ETH professor’s robot fear system is inspired by the human fear system. The latter is more potent than those of other species. On the one hand, it functions via the amygdala, the emotional center of many creatures. “Humans, however, also have a huge neocortex, which allows dangerous situations to be classified,” Benjamin Grewe explains: “If, for example, we see a lion at the zoo, it is this part of our brain that tells us that we don’t have to run away.”

“AI is not good at generalizing”

In order to train these two artificial brain areas, Benjamin Grewe uses deep Q-learning, a branch of reinforcement learning. The benefit of this approach: The researcher no longer has to show the AI thousands of images, but simply equips it with a scalpel in a simulation and allow it to figure out through trial and error which actions are successful and which are not. It receives a reward for successful movements, and for bad ones – for example, if it causes a vascular injury – negative feedback.

However, it will take another five to ten years before the robot fear system is actually in operation. Two problems in particular are troubling Benjamin Grewe: “AI is still relatively weak at generalizing,” he explains. “It has a hard time adapting from simulation to reality, or from one patient to another.” The second challenge: Algorithms are forgetful. “It is still difficult to make AI build on existing knowledge. I can point it towards a new problem, but then everything it learned before is lost.” However, this is a common challenge and does not apply exclusively to emotional AI.

Simulated emotions

To avoid misunderstandings: There is no AI on the planet that currently has real feelings or empathy. “It is always a simulation,” the neuro computer scientist Benjamin Grewe clarifies. For real feelings, the AI would first need a consciousness. “And we are nowhere near that point yet.”

Beware of manipulation

When it comes to emotion recognition, the challenges are more specific. “Emotions are not unambiguous. This is why machine learning systems struggle with them,” says Björn Schuller, an expert in the field, pointing out a key sticking point. People are diverse and express their emotions differently. And even if they do express them in the same way: Emotional expressions are often extremely similar, in particular in visual terms. “Frustration, for example, will usually involve a brief smile, which of course has nothing to do with joy,” Björn Schuller explains. Research, however, is increasingly closing in on a solution. “Modern visual emotion recognition systems no longer take a detour via the intermediate level – the smile – but learn 'frustration' and 'joy' directly.”

“Providers could exploit emotionally weak moments to trick people into buying expensive products.”

The systems are constantly improving. However, when they do make mistakes, the consequences can be severe. This is something that the technology impact assessor Armin Grunwald deals with every day. “Precisely because emotion recognition does not always work reliably, it is problematic to use it, for example, in law enforcement,” the philosopher of technology says. “It is for good reason that AI-based lie detectors are prohibited in courts of law around the world.” But reliability is not the only problem with emotional AI: There is also the risk of abuse. “Providers could exploit emotionally weak moments to trick people into buying expensive products,” says Armin Grunwald.

Read the full interview with Armin Grunwald here: Identifying technology risks in time

At the University of Augsburg, the risk of abuse of emotional AI is leading to a bizarre situation: Björn Schuller is not only developing systems that recognize human emotion. “Simultaneously, we are working on technical solutions that help people hide their emotions from these systems.” A scenario with all the makings of a Hollywood blockbuster.

Written by:

Illustration: Reza Bassiri