“Music makes me a better scientist”

Nobody knows the Ebola virus better than Pardis Sabeti. Viral pandemics are her special area of interest. And now, this genetic researcher is looking for a way out of the Covid crisis. Rock music helps her in that.

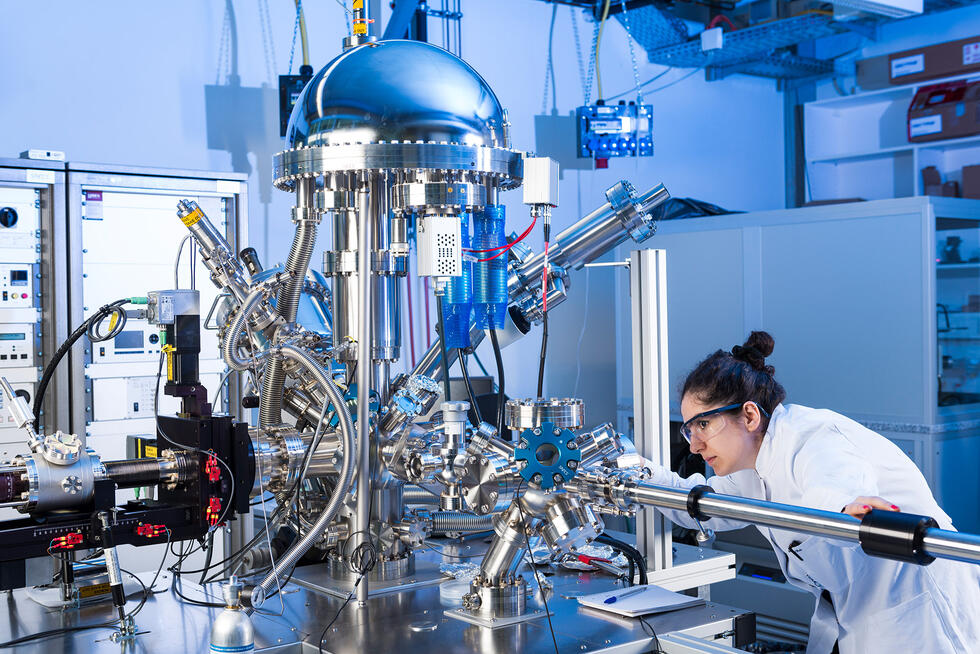

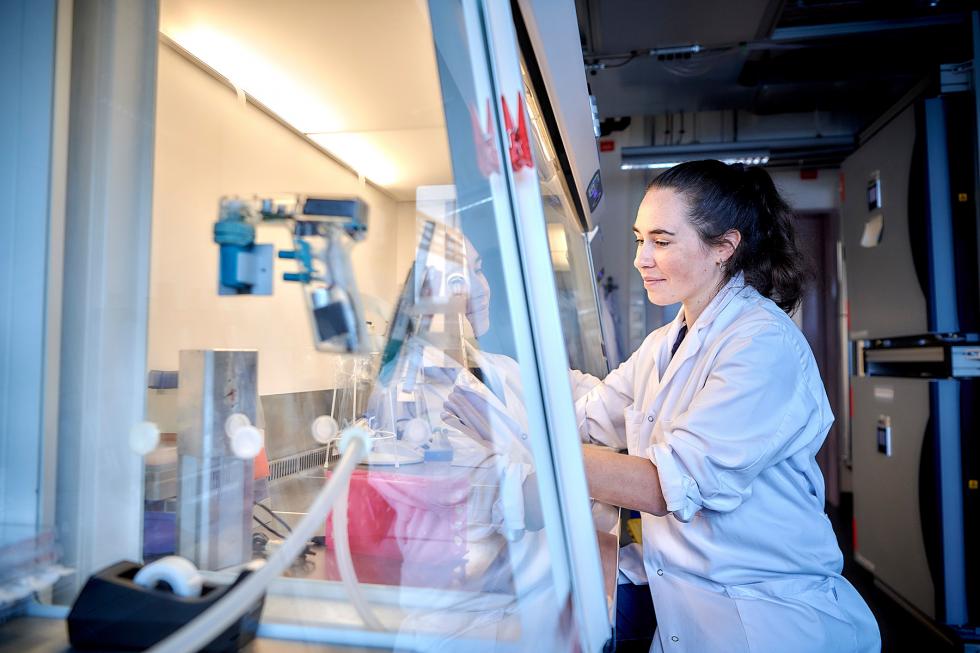

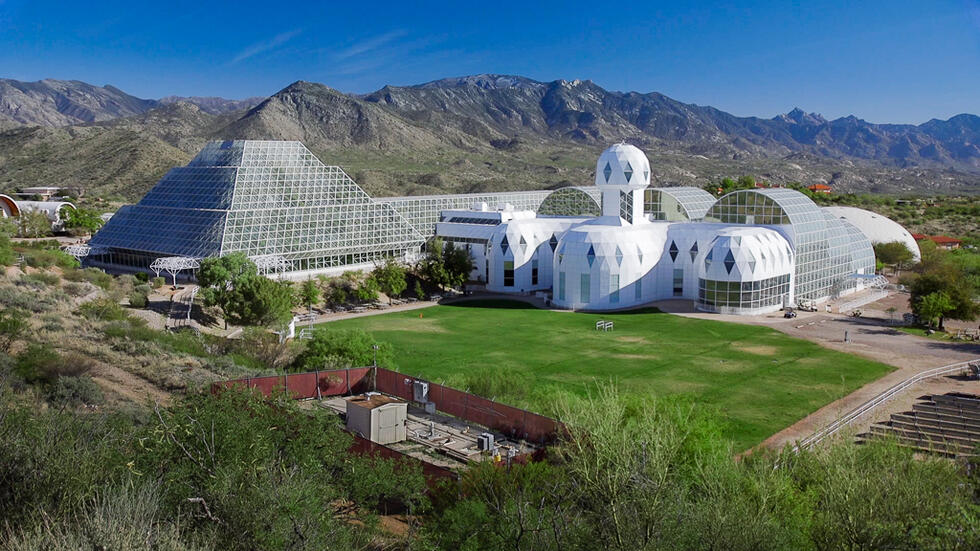

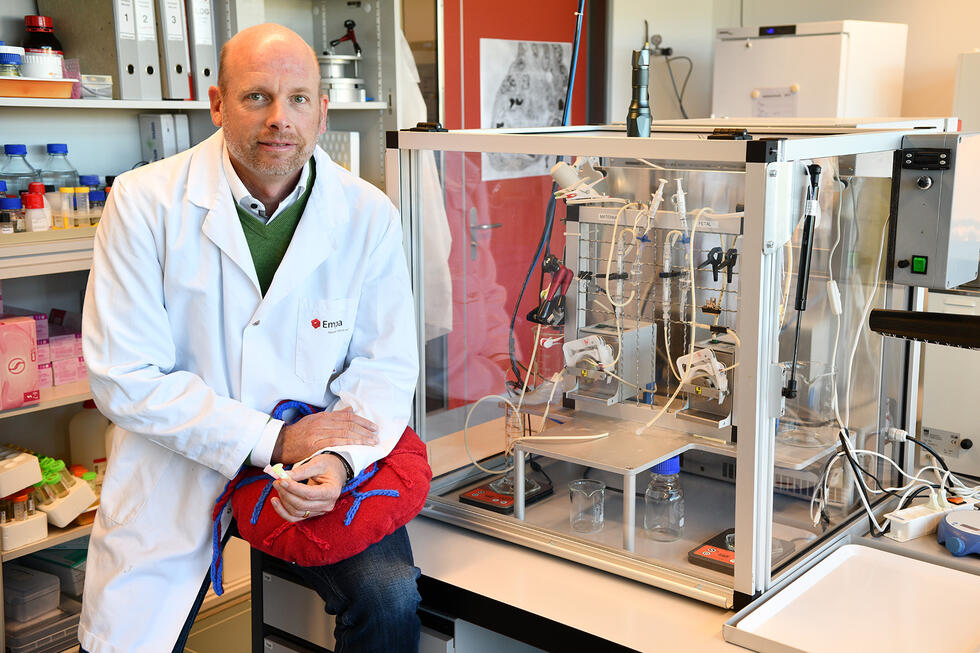

“I am still in my pajamas”, Pardis Sabeti apologizes when she answers my Zoom call on a July morning. But that doesn’t mean that she got a lot of sleep in, quite the contrary: It is ten o’clock in the morning, and Sabeti, a 44-year old Harvard Professor for Computational Biology and Evolutionary Genetics, has already spent several hours on her computer, emailing and meeting online with her research staff at the Broad Institute. The “Broad”, as everyone calls it, is located in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and jointly operated by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and Harvard University. It specializes in genetic research, and because it is one of the leading research institutes for infectious diseases, the pandemic put it into overdrive. “For the past four months, I've been working around the clock”, Sabeti explains – but mostly from home, which she calls her “bubble”: “The Broad doesn't like anybody there who doesn't have absolute reason to be there; my job consists mainly of finding and then managing the scientific talent: that’s how science works now.”

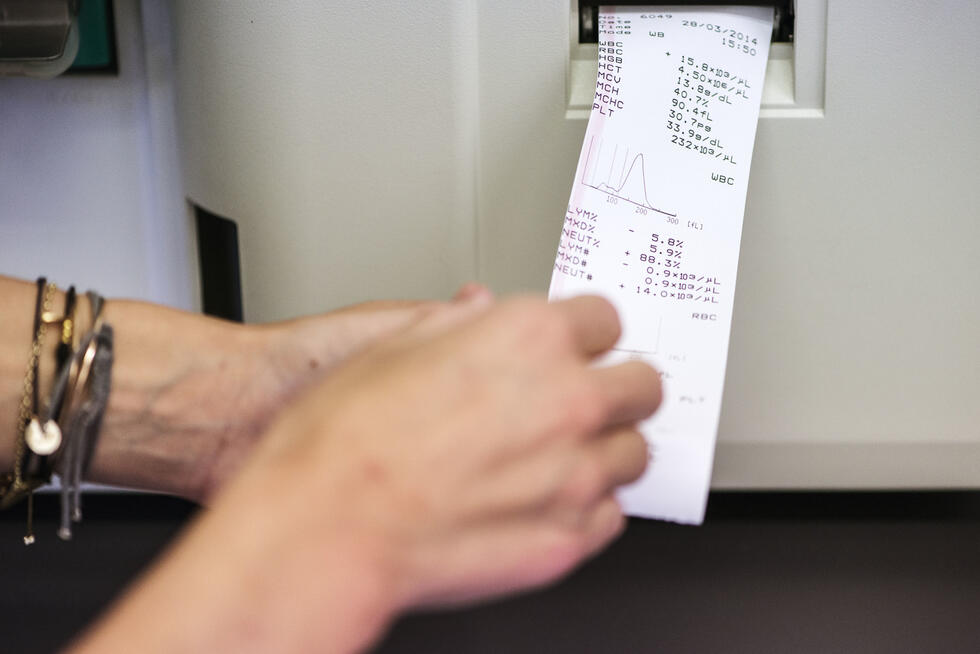

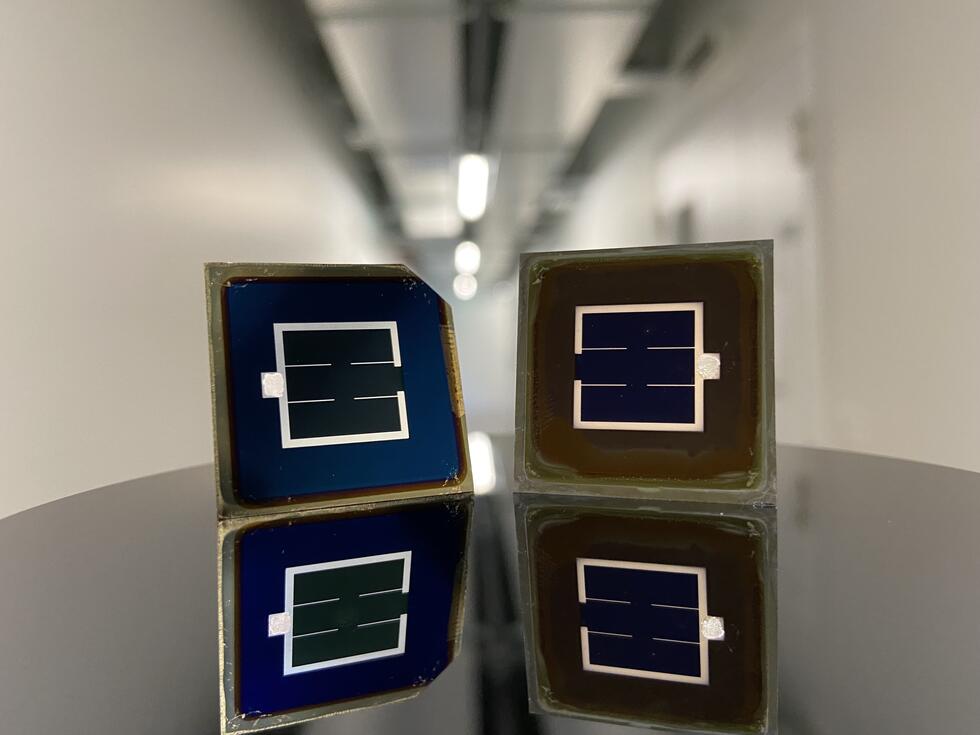

The Sabeti Lab’s staff of 50 researchers works tirelessly on refining the diagnostic tests for the Sars-Cov-2 virus: The first version of a test that the Broad released this summer was able to produce results within 24 hours; it came just in time for the beginning of the current school year. Without this test, hundreds of schools and colleges, as well as dozens of local government offices would have remained shut down until well into the Fall. The most recent version of the Broad test can deliver results within less than an hour, but it still must wait for approval from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

It seems like Pardis Sabeti had been preparing for this challenge all her life: After graduating from MIT in 1997, with a degree in Biology (see insert), she first went to Oxford on a Rhodes scholarship to earn a graduate degree in Genetics; she returned to Cambridge for a medical doctorate at Harvard, which she received in 2006, with highest honors. But rather than going into medical practice, as she originally intended, she decided to continue her research, accepting a professorship at Harvard. And in less than a decade, she rose to become a leading international specialist for pandemics: In 2014, the magazine TIME included her and her fellow Ebola researchers as “Person of the Year”, and in 2015, the same magazine named her one of its “100 most influential people”. In October 2020, she was elected as a member of the National Academy of Medicine, which is considered one of the highest honors in the field of health and medicine, not only in the USA, but internationally.

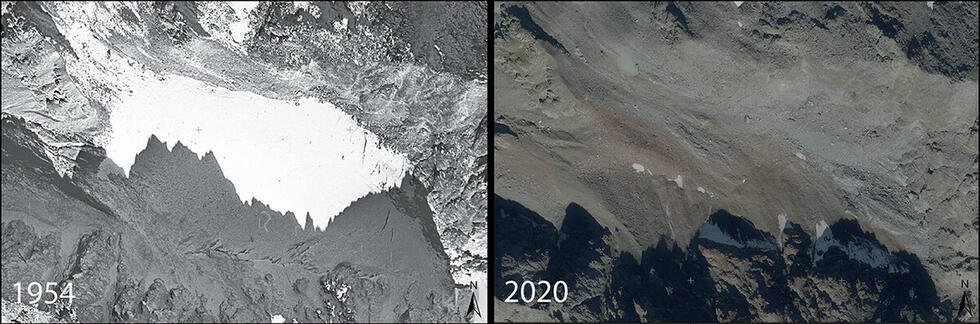

This fast and steep rise to success actually started with an idea that, as she remembers it, was considered “dumb” by the experts in her field: Rather than trying to use the fairly new tools of computational genetics to uncover new and unknown infections, she applied those tools to look for mutations in the human genome, which already well-known viruses had left behind like genetic “footprints”. For one, she believed that this could help to better understand how long populations had been exposed to those viruses – with longer exposure, those footprints tend to be spread much further throughout the genome. But this also can help to understand why some people are immune to certain viruses; this information can help mapping a path to a remedy for these diseases.

In 2014, when Ebola emerged as a global threat, Sabeti and her team were able to show through their research that this specific virus had its origin in Sierra Leone, West Africa; only a few months before the outbreak, there had been a single transmission from an animal (probably a bat, but monkeys and other wild animals are also carriers of that virus) to a human. More importantly, she was also able to prove that in this short time span, the virus had mutated in a way that it could be transmitted from human to human. It was this discovery that led to her inclusion in TIME magazine’s list of “100 most influential people”. But she appears to be wary of that celebrity status, which she sees as a “perverse incentive”: “There's a lot of recognition, there's a lot of fame for whoever can fix this pandemic. This is an insidious deadly threat that could kill some and could make others a lot of money.”

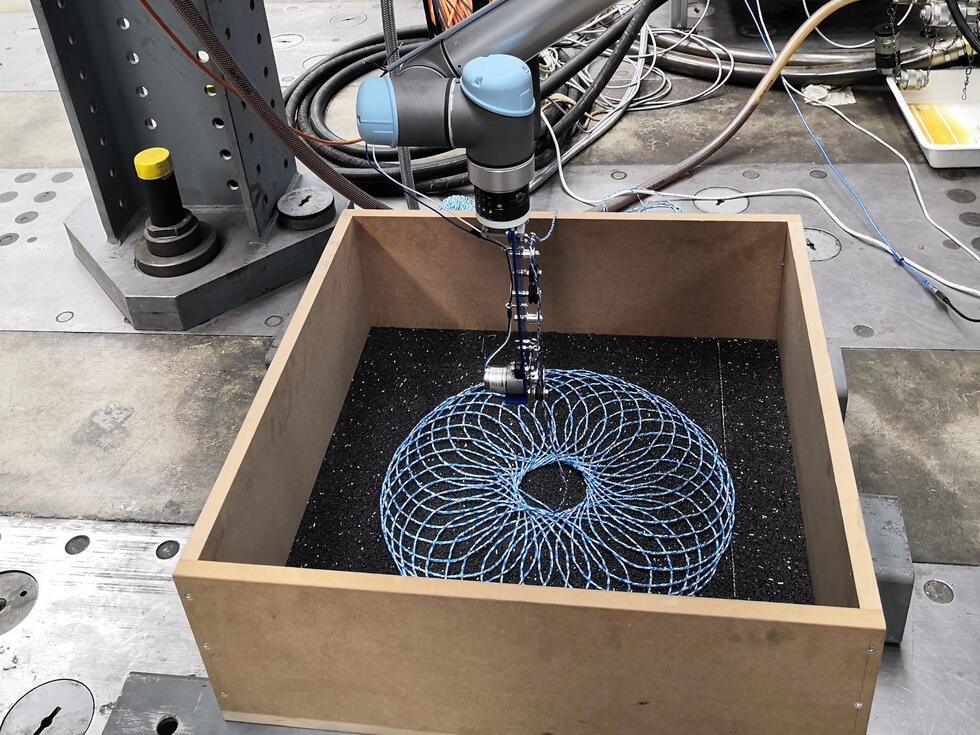

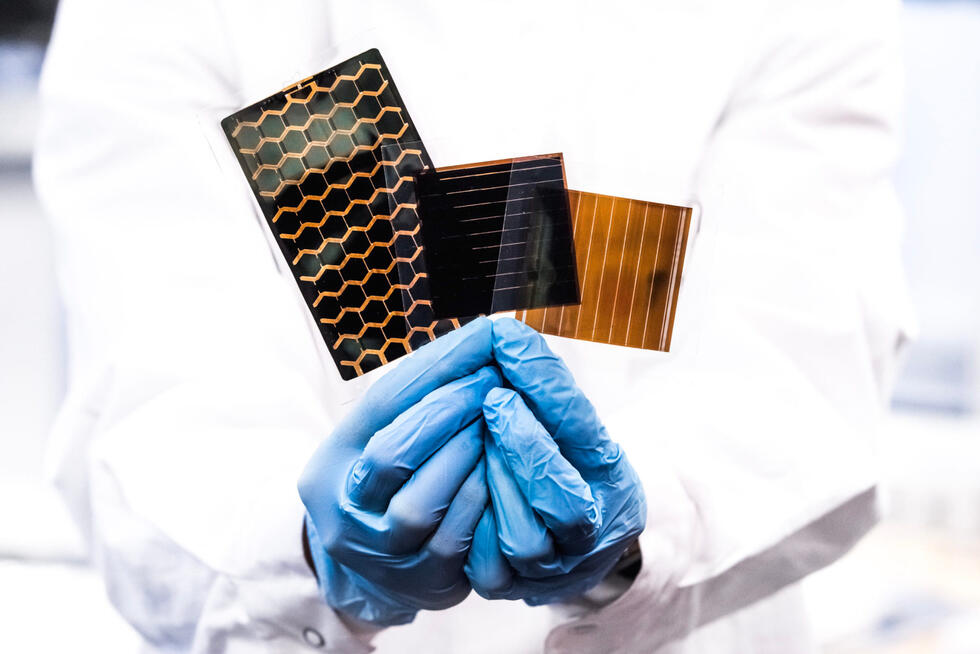

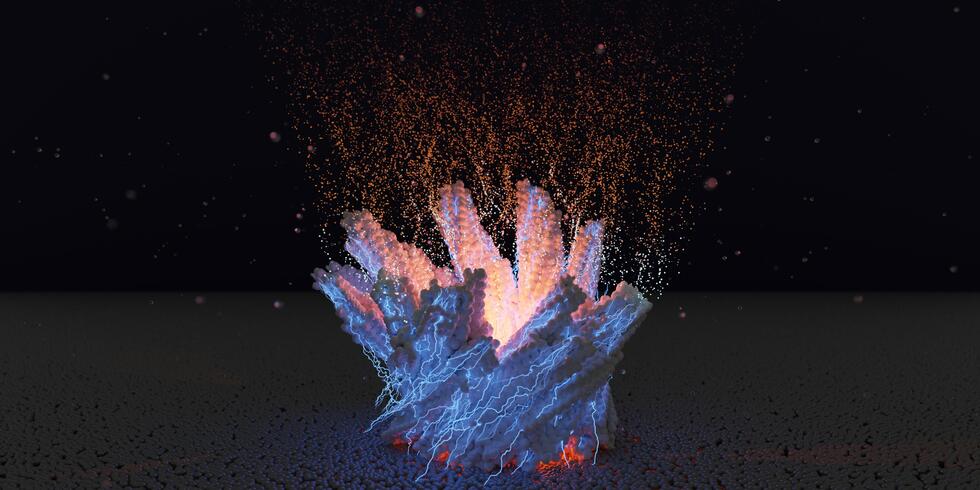

Tracing unknown viruses in the genome

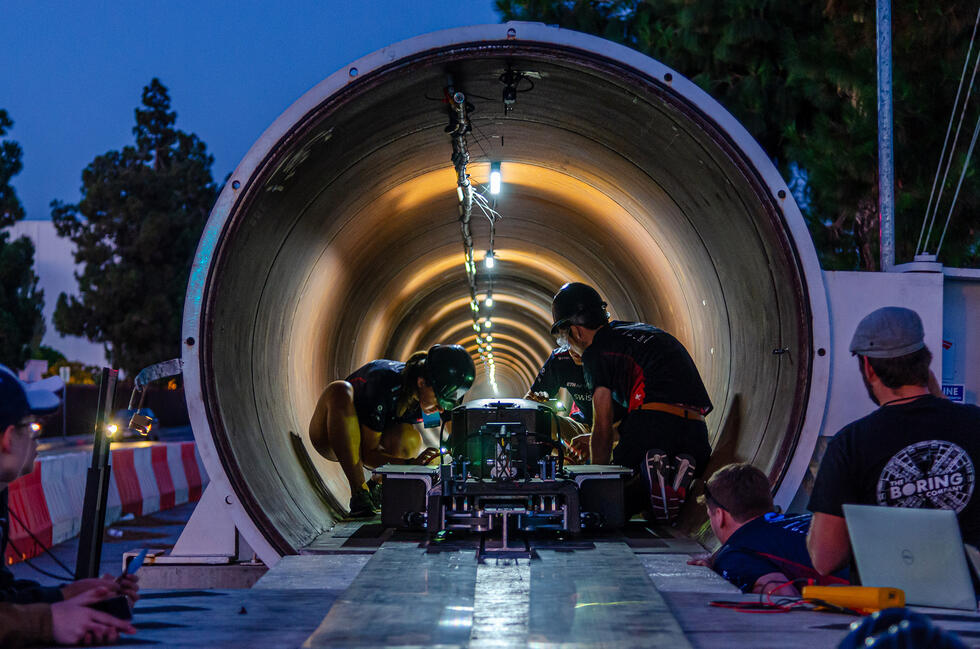

The recently discovered CRISPR-Cas method for gene editing, for which Emmanuelle Charpentier and Jennifer Doudna were awarded the 2020 Nobel Prize, has become a very valuable tool for Sabeti and her team: Using this method, they have developed a testing method that detects not only the Sars-Cov2 virus that causes Covid-19, but can differentiate all 169 known viruses that affect humans. This research is particularly relevant for regions where animal viruses can “jump” to human hosts and trigger new and unknown dangers which are hard to contain in a global society.

We need to find ways of making sure that all of that information is shared on an interoperable platform so that we can put all the pieces together

But it is not enough just to discover those viruses early and develop rapid diagnostic tests: Equally important, according to Sabeti, is the rapid dissemination and publication of those results. For example in pre-publication databases like bioRxiv, where scientific findings become accessible to the science community, long before they appear in journals: “We need to find ways of making sure that all of that information is shared on an interoperable platform so that we can put all the pieces together.”

An even more important issue for her is educating the public on the risks and mechanisms of pandemics, like the one we are currently experiencing: “Five years ago, we started Operation Outbreak in West Africa. This is an education module that teaches kids about the biology and the public health and epidemiology and government policy that's involved in outbreaks. The culminating event is an outbreak simulation that spreads a virtual virus via Bluetooth on student phones or phones that we give them, so that they can actually see the pandemic as the virus is jumping from person to person. We created real epidemiological models that track that spread; their challenge in the game is to stop the virus before it spreads”

No interest in an early warning system

For some years, Sabeti has been trying to establish a similar preventive system in the US, and she kept pitching that idea to private organizations, like the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. She also tried convincing the government, especially the Defense Threat Reduction Agency, which is part of the Department of Defense: “I've been pitching for a better surveillance system in the United States for the last six years, but that has just gone to deaf ears everywhere.” Her voice betrays her frustration about the fact that it needed an actual pandemic for her ideas to be taken seriously: “Our Health Care system is bananas, and our political discourse is bananas. I've been working with infectious diseases for 20 years, and I really don’t want to say ‘I told you so’. But at least we have a common language about it now.”

It's not only that people are dying of Covid. Many people have lost their jobs, and there are many people who are trapped indoors with someone that terrifies them, someone who abuses them

But does that make a difference anymore? As a consequence of denial and disinformation, especially from the White House, the US has tragically become the global “leader”, as far as new infections and casualties are concerned, with around 200’000 new cases reported every day (about 15 million plus in total, so far) and more than 280’000 people dead, a number which rises by a 1000 each day now – and no end in sight. But at least, everybody has become aware of the real dangers of such an outbreak: “It's not only that people are dying of Covid. Many people have lost their jobs, and there are many people who are trapped indoors with someone that terrifies them, someone who abuses them.” She sees it as “a giant failing of the most vulnerable among us.”

Not even in Boston, where she works and which is teeming with like-minded scientists, was she able to gain traction for her idea of an early warning system: “There's a lot of frustrations of that not coming together. I had many opportunities and I got a lot of people excited about the idea, but it didn't come together because no one was going to fund a woman to do this kind of work.”

Treated like a research assistant

This assessment seems hard to believe, considering all the honors and recognition that Sabeti has received (see insert). Is she really sure that this was a case of gender discrimination? That question obviously touches a nerve: “This happens to me regularly!” And it is true that there is a clear gender gap in American research funding: A female researcher’s chance to win a major research grant is about ten percent lower than that of a male colleague, and when she gets funded, it is on average 20 percent less money than what the male researcher gets. And despite all her awards and prizes, Sabeti often feels that her male colleagues treat her like an assistant: “I've had the opportunity to present to some of the world's most influential and powerful people. Most of the time, when I presented my idea, they love it – then they figure out what man is going to do it. They treat me as a research assistant! I go to conferences, and men expect that I clear the dishes. My male students will get major grants, and all I was getting were baby grants!”

I often considered throwing in the towel but I owe it to other women to continue my work

Sabeti admits that many times, she contemplated just giving up. And she might have gotten serious about it, if it weren’t for a major award that she received this summer: She was awarded a million-dollar grant – previously known as the “TED Award” – from the Audacious Project, which is the organization behind the TED conferences. But what mattered more than the money itself and what made the award “transformative” for her is that the prize (which she shares with her Nigerian colleague Christopher Happi) is funded to a major part by McKenzie Bezos. The former wife of Amazon founder Jeff Bezos used her billion-dollar divorce settlement to support other women. “I often considered throwing in the towel”, Sabeti admits. “But I owe it to other women to continue my work. But women can cause trouble for other women, too, when there are only a few seats at the table, and everyone's trying to get one, that creates an incentive to knock other women out. But the Audacious prize, and especially that is shows how they believe in us, was truly inspiring for me, and I am very grateful for that.”

New perspective after a serious accident

Another event, that deeply reshaped her outlook on life, happened five years earlier, on July 15, 2015: “I was at a conference at the Yellowstone Club in Bozeman, Montana. I allowed myself to be talked into going along on an ATV ride through the mountains, although I really did not like this idea. But I let everybody convince me that everything was absolutely safe, despite of what my instinct told me. There was a switchback, and the driver just had trouble turning. We went straight down, we hit a tree, the ATV flipped, and I was catapulted on the boulders banging my head, shattered my entire pelvis and both my knees. It is shocking that I'm alive.” But staying alive requires more than not dying: Sabeti needed 30 hours of emergency surgery over the next four days; 30 steel rods were used to fix her shattered pelvis. And she spent another year in physical therapy to literally get back on her feet again.

“My physical therapist asked me: what was your part in what happened? And I was offended at first – I had not played a part, I was just the victim! But over time, I came to realize that accepting responsibility is actually empowering – and that failing was that I had agreed to something that I really did not want to do in the first place.” The lesson that she took away from that experience was that never again she would hand someone else the control over her: “I can’t ever be a passenger. I need to handle my own risks, and that is also why I work on risky things like Ebola – because I know the risk and I love thinking through all the possibilities.”

What would she do, if she could not do research anymore? There is definitely one alternative: For some ten years she has been front-woman, lead singer, and songwriter for the alt-rock band “Thousand Days”, and has recorded a number of albums (they are available on Spotify, for example). The newest Album with new song material was scheduled for release in 2020, but the Covid-19 pandemic pushed that date to 2021. “Most of the songs are ready, but I simply do not know when to finish the rest of the recording. My guitar player and co-songwriter Bob Katsiaficas might have to carry me over the finish line.”

A better scientist through rock music

Serious science and rock music – how do they go together? How do her colleagues feel about that? “Oh, most of them probably don’t know anything about ‘Thousand Days’, I suppose.” There may be some “who might dismiss me for that, but I do find that ultimately, it really does improve my science. For me, the ability to just create and think keeps all those neurons active and fired, and science requires actually so much creativity and exploration and discovery.”

Is she ever concerned that she or her family might become victims of Covid-19? “I am not too concerned about myself. But I actually lost a loved one – my old nanny Fathia, who came to my mother’s family when she was a young girl and who helped raise me, died of Covid-19. The tragedy was not so much that she passed away; she was old and at that point in her life were her quality of life was low – the tragedy is that she passed and none from her family, none of her loved ones could hold her hand. And that to me is the awful, dehumanizing thing about infectious diseases when we don't do it the right way.”

Is this fear what drives her, what motivates her? “There are so many drivers at this point; I need nothing more to motivate me. Every day I get up and say, we got to get out of the situation.” But will we find that way out? “We will eventually get out of the situation, but we will lose a lot of lives in the process, lose a lot of jobs, and a lot of livelihoods in the process. Maybe we'll learn, maybe we won't – nothing surprises me anymore. But yeah, I'm hoping I'm hoping we do.”

Main awards and accomplishments

Pardis Sabeti, born on December 12, 1975, in Teheran, grew up in Florida.

- In 11th grade at Trinity Preparatory School in Orlando (Florida), she won a National Merit Scholarship Program award (the same award that had been given to Bill Gates, founder of Microsoft, John Roberts, Supreme Court Judge, and a number of Nobel prize winners, among them Joseph Stiglitz and Paul Krugman.)

- Rhodes Scholarship after graduating from MIT with a degree in Biology and a perfect grade average in 1997;

- 2002 Doctorate in Evolutionary Genetics at Oxford;

- 2006 Doctorate “summa cum laude” in Medicine, Harvard University;

- 2008 David & Lucile Packard Foundation fellowship

- 2009 New Innovator Award from the National Institute of Health (USA);

- 2012 American Ingenuity Award, Smithsonian Magazine (another award winner that same year was Elon Musk, founder and CEO of Tesla and SpaceX);

- 2012 named Young Global Leader, World Economic Forum, Davos;

- 2014 Vilczek Prize for Creative Promise (an award given to immigrants in the United States) for excellence in the field of biosciences;

- 2014 named Time Magazine’s Person of the Year (as part of the Ebola team);

- 2015 named one Time Magazine’s “100 most influential persons”;

- 2016 selected as Howard Hughes Medical Investigator;

- 2017 Richard Lounsbery Award, a joint award from the National Academy of Sciences (USA) and the Académie des Sciences (France);

- 2020 elected to the National Academy of Medicine (USA)

Written by: Jürgen Schönstein

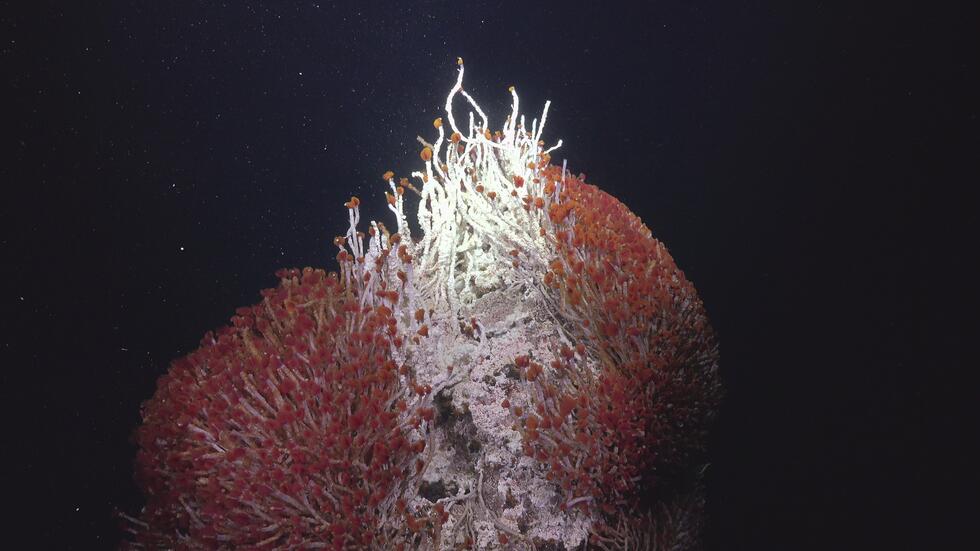

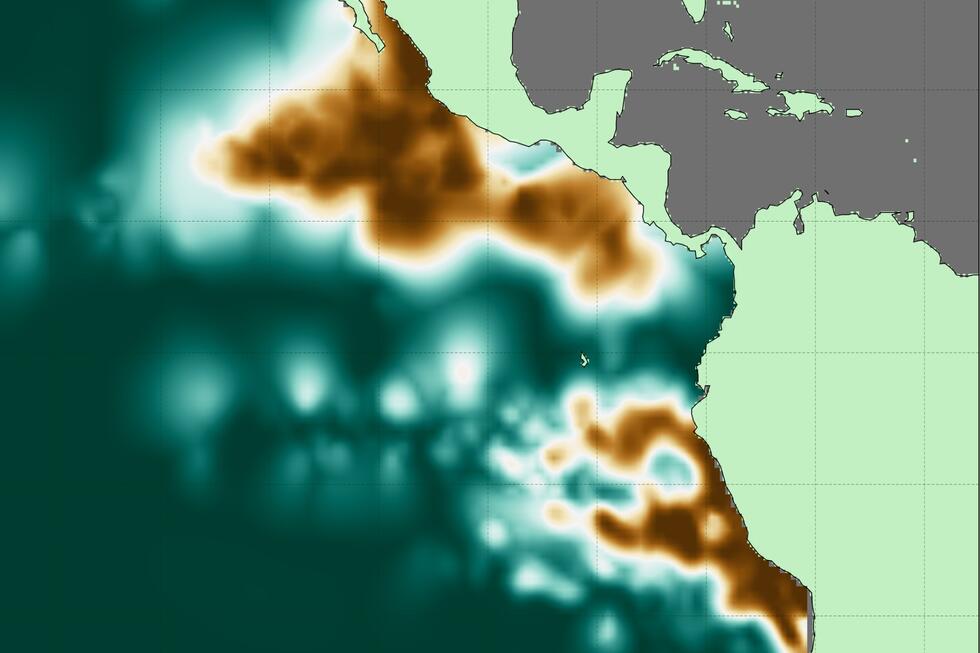

Photos: Courtesy of Broad Institute

Illustration: Enrique Quintero