“We need to become climate positive.”

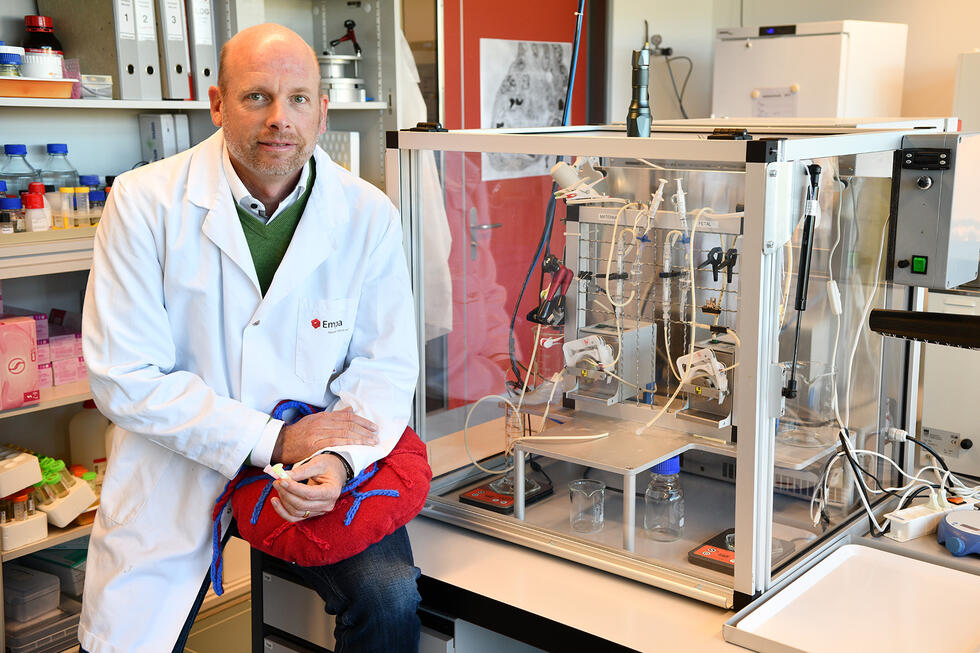

Michael Braungart is the enfant terrible of environmentalists. Be it recycling or climate neutrality – the initiator of the cradle to cradle principle takes a tough stance on conventional approaches. An interview about climate-positive products, tire abrasion, and synthetic plankton.

Michael Braungart, what are we doing wrong when it comes to environmental protection?

We believe that we are protecting the environment by destroying as little of it as possible. It is drilled into our heads: Use your car less! Generate less waste! Use less water! We are told to conserve, to get by without things, and to avoid. But true environmental protection is about more than just curbing the destruction. Many companies and cities are trying to become climate neutral, but that’s not enough. Climate neutrality will not save the planet. We have to become climate positive.

So in your view, the UN climate targets are not ambitious enough?

Definitely not. The goal of limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees by the year 2100 only postpones the destruction of humanity by a few generations. Our objective should be to return to the same level of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere by 2100 as we had at the beginning of the age of industrialization. To achieve this, we need new strategies to combat climate change. We have to actively recapture CO2 from the atmosphere.

And how can we accomplish this?

By making meaningful interventions in nature, for example by means of reforestation or by regenerating the soil we cultivate instead of continuing to degrade it. Technology can also pave the way, for example with systems that extract CO2 from the atmosphere and bind it in the soil.

So you believe that a climate-positive future for humankind is possible?

Yes. We just have to look to nature for inspiration. After all, a tree is not climate neutral either, but climate positive. Should we humans be satisfied with being less capable than a tree? We have to liberate ourselves from our modesty. I am firmly convinced that humankind has the potential to create things that benefit the environment.

Why have we had so little success so far?

This has a lot to do with our culture, and especially with religion. Christianity, Judaism, and Islam all say: “You are bad and only God can redeem you.” So we can’t be good, at most we can be a little less bad. This is not an optimistic conception of humanity. We should understand our existence as an enrichment for the planet, not as a burden. I only realized all this when I lived in China for two years. People there think very differently – even feces have a value. When you visit rural areas, after you have eaten, you stay until you’ve been to the restroom to leave the nutrients there. So there, people always think in terms of cycles. In the Western world, on the other hand, we humans do not define ourselves as a part of the biosphere. Organic is only possible in our absence. Isn’t it remarkable that there is not a single organic label that allows the use of human excrement as fertilizer?

“In many cases the current circular economy is like riding a Ferris wheel – you always end up in the same place.”

Now, however, the concept of the circular economy is also teaching Western culture to think in terms of cycles.

Yes, but in many cases the circular economy is like riding a Ferris wheel – you always return to the same place. We are merely optimizing what already exists while failing to consistently focus on developing things for cycles. A large part of what we call recycling is actually downcycling.

Can you give an example?

When the 46 steel alloys used on a Mercedes are turned into primitive structural steel, all the valuable non-ferrous metals are lost: chromium, nickel, cobalt, manganese, and tungsten. And shredding used plastic bottles to make park benches is not the circular economy; it is only the reallocation of the landfill. And it gets even worse when – as in Amsterdam – the surface of bicycle paths is made of used plastic bottles. As a result, microplastics end up in the groundwater.

“Tire abrasion accounts for more than half of the microplastics in European rivers.”

You are addressing a very topical issue. Many people are now aware that microplastics end up in the water due to washing textiles or using personal hygiene products. Are there other sources?

Many things that experience wear and tear release microplastics. The shoe wear of the average person alone releases some 110 grams of microplastics into the environment each year. However, one of the most serious problems is tire abrasion. It accounts for more than half of the microplastics in European rivers. Nowadays, car tires last twice as long as they used to, so intuitively everyone thinks: “That’s great for the environment.” But manufacturers use almost 500 different chemicals to make tires last as long as possible. By making tires last longer, we’ve perfected doing the wrong thing instead of taking a step back and asking: What abrasion benefits the environment? Road markings are also a contributing factor. Almost ten percent of the microplastics in the North Sea originate from pedestrian crossings.

“We lost roughly eight days of life expectancy to Covid, but we lose more than five years to particulate matter.”

Another major environmental problem is particulate matter. How and where does it originate?

Particulate matter is not only created outdoors by emissions from cars and factories, but also indoors. One of the main causes are laser printers. Printing a single page releases up to two billion particulate matter particles. This has a devastating impact on our health. We lost roughly eight days of life expectancy to Covid, but we lose more than five years to particulate matter.

So the air is not only bad outdoors, but also indoors?

Yes. Together with students, I measured the air quality in German kindergartens, and in most cases, the air inside was even worse than outside. One major factor are the pollutants in floor surfaces. Although floor coverings containing PVC are now recycled, this does not change the fact that they are toxic. Here, as with car tires, we have perfected doing the wrong thing.

Are there plastics that do not harm humans and the environment?

Certainly. I helped develop plastic packaging that you can simply toss away in the forest. The film material degrades within two hours, supplying nature with nutrients in the process. A wide variety of biodegradable synthetic fibers are already available for the production of textiles, such as viscose fibers made from regenerated cellulose. Even polyester – which is a problematic material because microplastics are released during washing – could be made to be biodegradable. To do this, however, we would first have to find a way of filtering out the harmful components from the polyester stream. In this way, artificial plankton could be created, which could then serve as nutrition for algae and microorganisms in the sea.

About thirty years ago, you co-created the cradle to cradle principle. How does this approach fulfill the demand for products to benefit the environment?

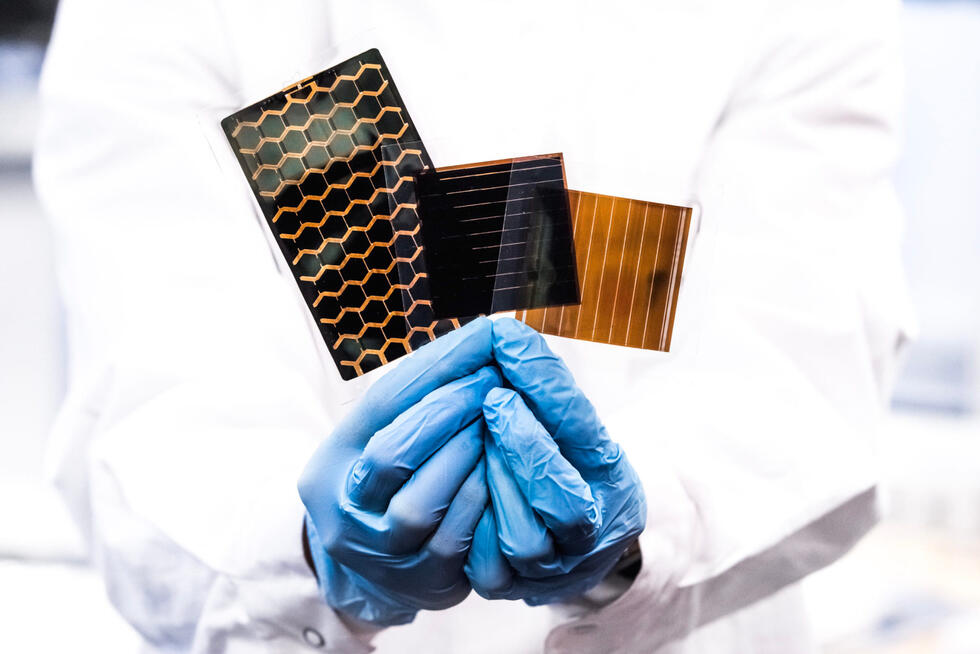

Cradle to cradle products are designed to have a positive effect on the environment. We distinguish between materials for the biosphere and materials for the technosphere. Everything that is subject to wear or is used up, such as car tires or detergents, is designed to benefit the biosphere. And all raw materials from the technosphere, for example for the production of washing machines or televisions, flow back into new products. This means that there is no longer any waste, but only “nutrients” for the biosphere and technosphere. If we design products in this way, we do not need a downstream “treatment plant”, because the filter is already integrated into the initial design.

C2C: Nutrients for biological and technical cycles

Cradle to cradle (C2C) is an approach for a continuous and consistent circular economy. The aim is to return all materials from products as “nutrients” to biological or technical cycles, either by allowing them to decompose or by using them for new products. The concept was initiated by Michael Braungart and the US architect William McDonough. In 2002, the duo published the acclaimed book “Cradle to Cradle: Remaking the Way We Make Things.” Since 2010, the Cradle to Cradle Products Innovation Institute has been awarding C2C certification to regenerative products.

Can you give some examples of cradle to cradle products?

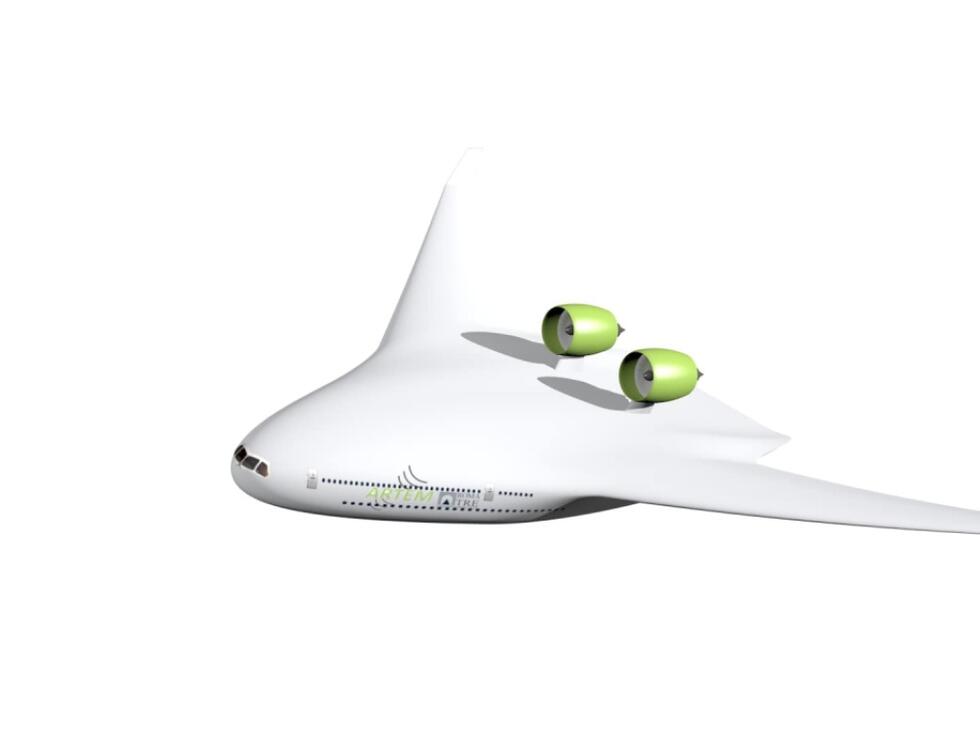

The very first C2C product, which was launched in 1992, was a biodegradable fabric for seats in buses, trains, and planes. Normally, the fabrics used are so toxic that they must be incinerated as hazardous waste. The fabric from the Climatex brand, in contrast, is quite different; you could even eat it. In the Netherlands, there is a company that produces carpeting that actively filters particulate matter from the air. And the Danish shipping company Maersk has been building its freighters according to the cradle to cradle principle since 2015. All parts are made of materials that do not release pollutants into the sea and can be reused in other products at the end of their service life.

Does cradle to cradle pay off in economic terms?

The Climatex fabric is 20 percent cheaper to produce than conventional fabrics. The principle is gaining ground precisely because it is economically viable. The moral aspect must not be the driver, otherwise companies would not be interested in it. In the meantime, there are more than 11,000 cradle to cradle products worldwide. The concept is increasingly gaining traction in Europe and the United States, but also in China. The Chinese childcare products manufacturer Goodbaby, for example, has converted its production to the cradle to cradle approach.

“We need a completely new understanding of quality, otherwise we will never stop producing waste.”

The automotive industry, by contrast, has barely embraced the approach so far, has it?

Here, too, there are initial success stories. BMW recently announced that it will start developing cars according to the cradle to cradle principle. And Porsche is working on a synthetic fuel produced by extracting CO2 from the air. But the approach can only really be implemented consistently if we change the business models. After all, most products have a quality problem. We need a completely new understanding of quality, then we also stop generating waste.

I am afraid you will have to explain.

A car contains more than 200 plastics that were not developed with recycling in mind. The existing business model does not permit any other approach, because the materials have to be as cheap as possible. But if you were to sell only the right to use the car instead of the car itself, higher-quality plastics could be used. The manufacturer would remain the owner of the object and would essentially only market the service of driving a car. Then, instead of dozens of different types of plastic, only three or four high-quality materials could be used. These could be bonded together in a reversible manner, for example using enzymatic adhesive bonds, allowing them to be separated into the individual materials when cars reach the end of their service life.

So car manufacturers should stop selling cars?

Not only car manufacturers. Such a business model would also be conceivable for washing machines, for example. As long as such appliances are sold, the manufacturers have an interest in them breaking down after a certain time. But if the washing machine were to be provided by the manufacturer as a service, it would be in their own best interest to ensure that it has the longest possible service life.

"Nobody wants to own a window. What we actually want is a clear view and thermal insulation.”

Ownership is losing importance anyway – the keyword here is the sharing economy.

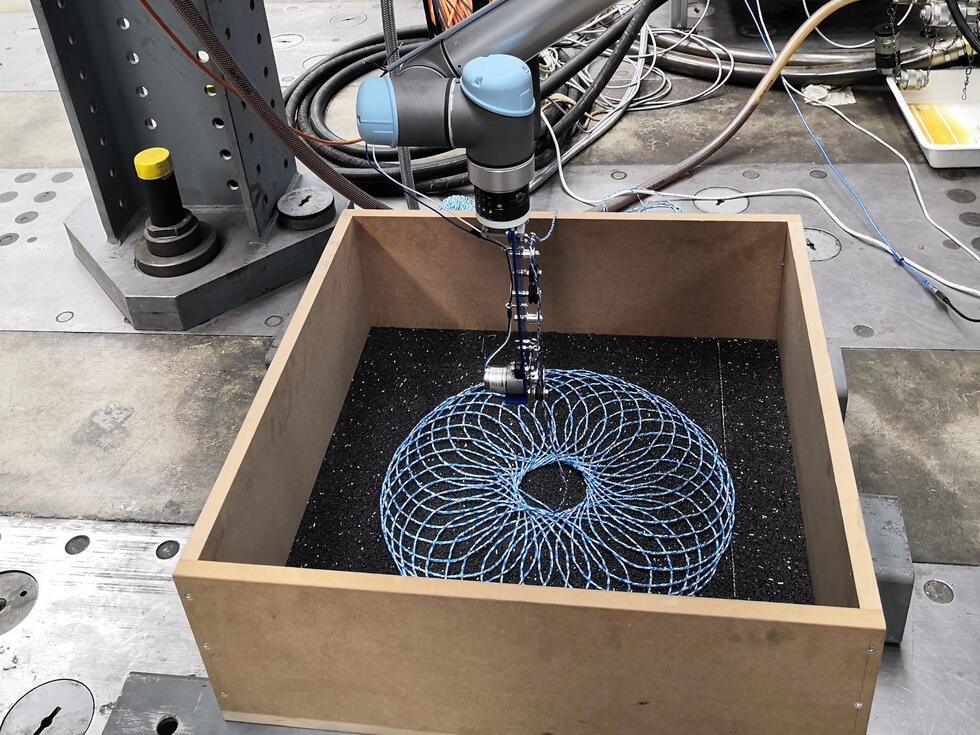

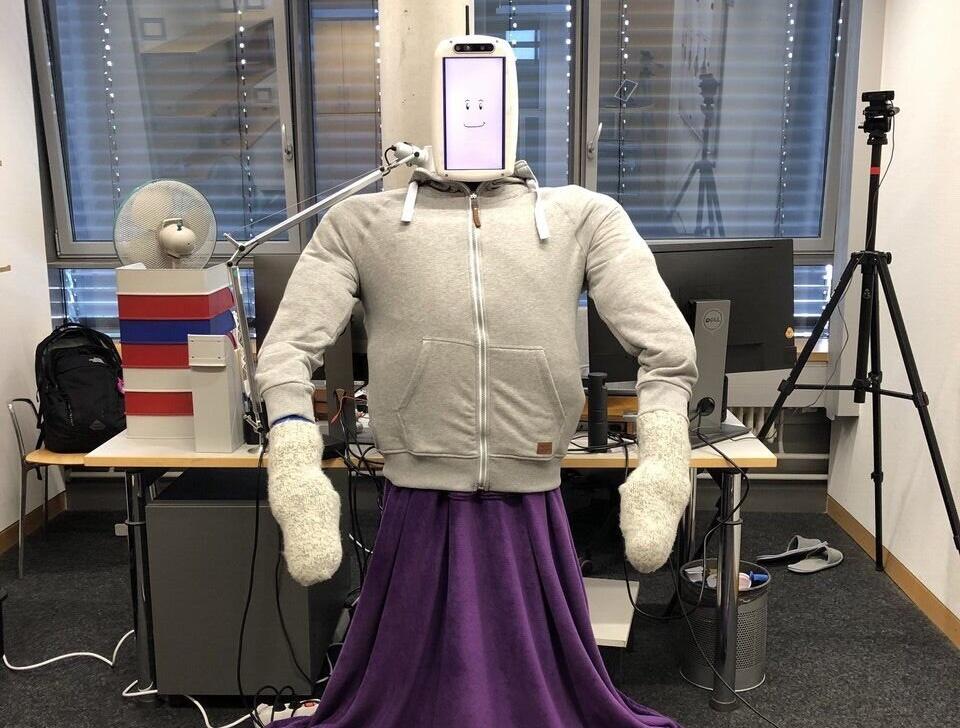

Correct. Car sharing is one example of the “use, not own” formula. This concept will also catch on in other areas. No company wants to own a robot – it only needs the result of what the robot can do, for example spot welding. And nobody wants to call a window their own. What we actually want is a clear view and thermal insulation.

Our conversation so far has frequently touched on plastics. What role do non-renewable raw materials such as metals play in cradle to cradle products?

Their role is similar to that of plastics: Rather than using many different cheap materials, we should use just a few, but better and more attractive ones. In cars, for example, one could use just a few steel alloys that are very high quality – and therefore retain their value. I could definitely imagine that such alloys could be of interest to investors. Today, vast sums are invested in metals that are simply stored in a warehouse. In the future, the car could be the warehouse for such metals.

“The complete switch to e-mobility will not be possible if we continue to use copper so wastefully.”

What is the impact of the e-mobility boom on finite raw materials? Where do you see bottlenecks?

We will soon run out of copper. The complete switch to e-mobility will not be possible if we continue to be so wasteful with this resource. Half of our copper reserves have already been depleted, but for electric motors, we need more of the material than ever. In the future, we should only use copper for electric motors, where it is really necessary due to its excellent conductive properties. Wherever possible, for example for power lines, we should use aluminum. This is a sound alternative, because there are still more than enough aluminum sources.

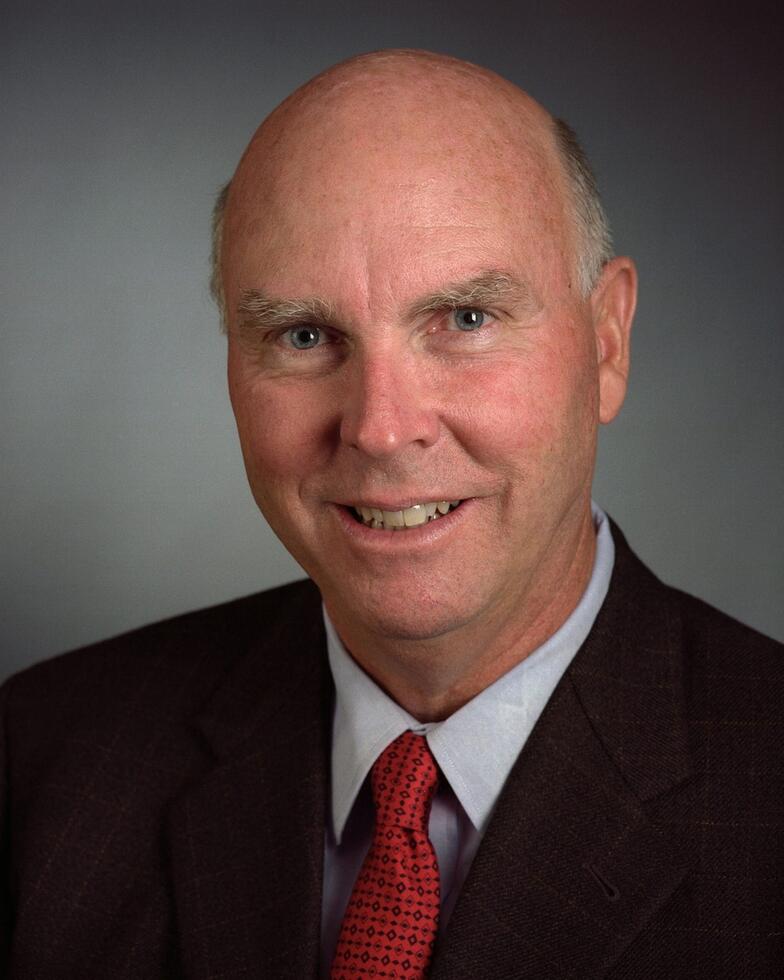

About

Michael Braungart, born in the German town of Schwäbisch Gmünd in 1958, is a professor at the Erasmus University Rotterdam and at the Leuphana University of Lüneburg. He is the founder and Managing Director of Braungart-EPEA, an international environmental research and consulting institute headquartered in Hamburg. He initially studied chemistry and process engineering, among other places in Constance, Darmstadt, Hanover, and Zurich. In the 1980s, he was active in the environmental organization Greenpeace. In the 1990s, he developed the cradle to cradle principle in collaboration with the US architect William McDonough. The author duo has since published two books. Michael Braungart has received several awards for his work, including Time Magazine’s “Hero of the Planet Award” and the “Golden Flower of Rheydt”, Germany's longest-standing environmental protection award.

Explainer videos: What is cradle to cradle?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fP8PRA-OajU

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QMsF1P-_vWc

Cradle to cradle products

Goodbaby - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SXL-yDH8Stk

Maersk - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PRgp9tcOwaw

Climatex - https://www.climatex.com/en/sustainability/cradle-to-cradle/

Written by:

Illustration: Stefano Grassi