“There is no one-size-fits-all formula for the city of the future.”

More and more people are flocking to cities, and urban planners are facing major challenges. Are cities growing upwards or outwards? Do they have to be completely rethought? In this interview, Sacha Menz, ETH professor and co-founder of the Future Cities Lab Global Program, explains what the city of the future could look like and why cultural factors will play an important role.

Naratek.com: How should one envision a city in 100 years?

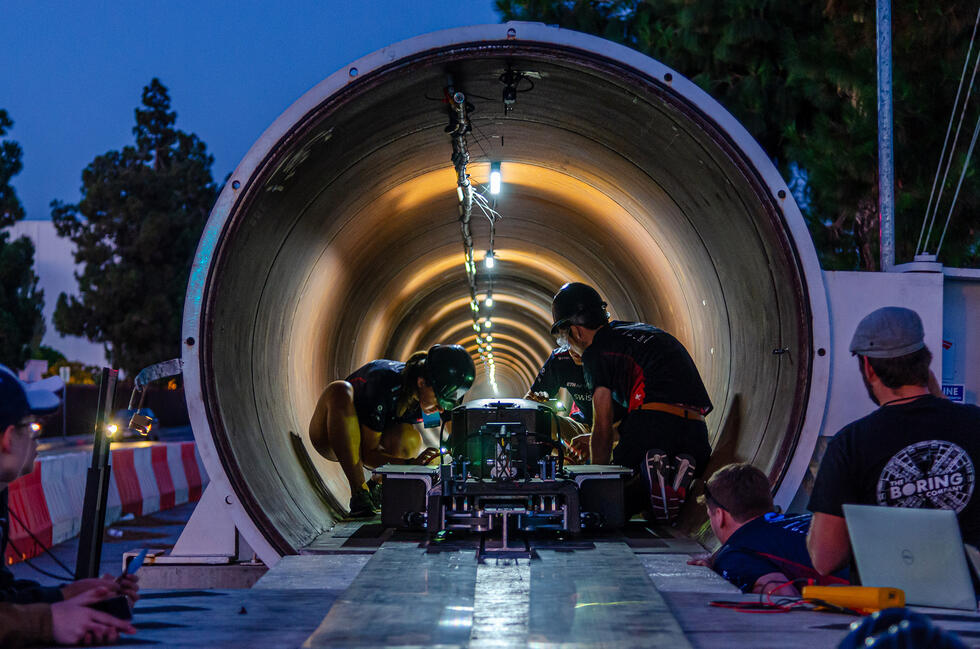

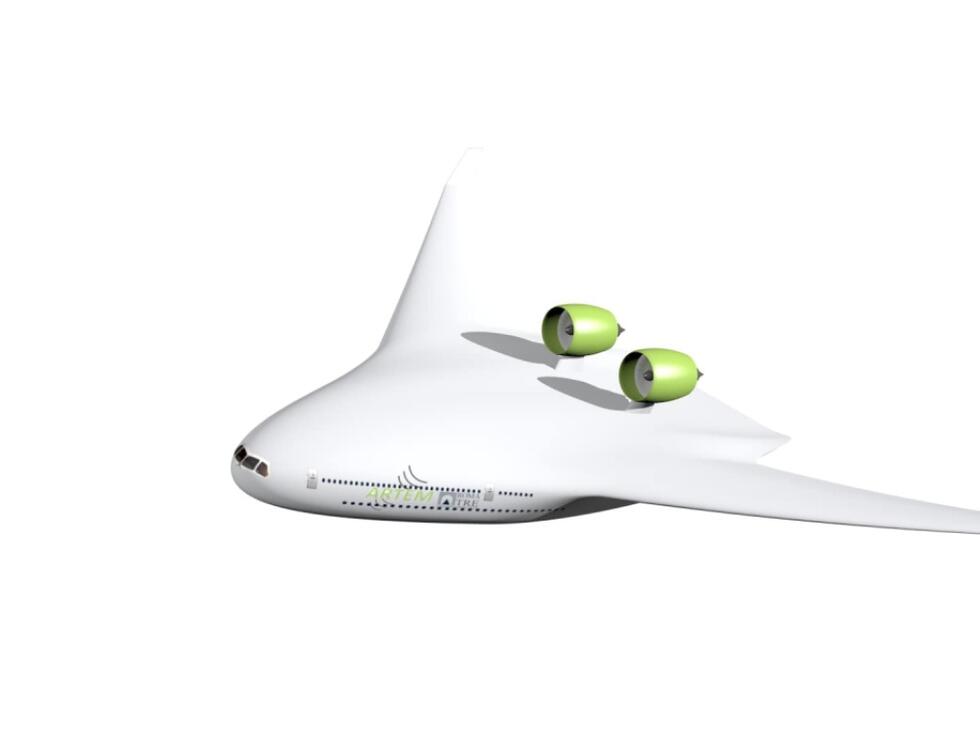

Sacha Menz: Historically, cities have never stopped evolving. However, there will no longer be major redevelopments like those that took place in 19th century Paris, because cities have learned to deal with existing structures, to expand and densify them. The traces of the past and present will remain. In one hundred years, many of today’s urban elements will still be recognizable. What will change, however, is the infrastructure, for example with regard to mobility. We can already now observe the speed of this development. At present, it is the needs of people that determines the direction, but in the future it will be nature that will define how our cities evolve.

So in 100 years, there won’t be any futuristic super cities like the ones portrayed in science fiction movies?

You mean like in “Blade Runner 2046”? This movie paints a grim picture of our future. I believe we will succeed in coming up with more appealing future cityscapes: The good elements will be solidified, those that we don’t feel comfortable with will not prevail and will thus be abolished.

Which discomforting elements are you thinking of?

Hard and reflective surfaces, for example, have a negative impact on the wellbeing of cities because they cause what are known as heat bubbles. There is also the problem of noise. What is more, the benefits of densification are frequently overestimated: It is based on a real estate economy that wants to squeeze as much profit as possible from plots of land. We know that nowadays, cities tend to spread out horizontally.

Which impacts the landscape.

Precisely. This raises the question: How can we strike a balance?

So building as high as possible is not the right approach after all?

Cities are determined by culture, the economy, and geography. Singapore, for example, has rigid city boundaries. If more people move into the city, there is no alternative to building upwards. In such a culture, the people’s willingness to build vertically is higher than here, where many still have grandmother’s garden in the back of their minds. There is no one-size-fits-all formula for the city of the future.

Let’s return to Switzerland: Where are cities like Zurich heading over the coming years?

In Zurich, new residential areas are currently being developed. One of the first examples was Zürich-Nord, which was, however, based on a functionalist concept from the 1980s: The credo was: “This is where you live, that is where you go to school, and all the shops are located over there.” Nowadays, urban planners are smarter: In Altstetten, for example, a neighborhood is developing with a healthy mix of walkways, greenery, and dense and less dense sections and functions. Zurich is gradually becoming a decentralized city: It is developing several centers, as can be seen in London and in the urban planning of the 60s.

In which cities do you currently see the most promising developments?

I find what is happening in Kings Cross in London very interesting: Here, existing buildings – the images of the past that we cherish – are being cleverly integrated. But I also see fascinating concepts in Singapore or in Japan, for example, mixed-use, layered residential space with public functions, healthcare, and multiple generations in the same building. Some of these buildings are as large as neighborhoods.

Where do you see the main challenges for the city of the future?

Urban development is based on legislation and planning regulations. This means that for new types of districts, the land utilization regulations, ratios, and usage types must be reconsidered and made more flexible. So a great deal has to happen at the political level. But this takes time, because it also affects private property.

So it requires individuals to change their mindset?

Let’s put it like this: The conventional zoning plan, which has served us well until now, has outlived its usefulness.

Why?

It plays into the hands of functional and territorial thinking, and these hinder future-oriented development. We need people with visions and the courage to actually implement new models.

So the basic attitude of the people has to change?

If people are not prepared to give up certain amenities and existing conditions, it will be difficult. In the 1950s, the average living space per person was about 35m2. Today this number lies at more than 50m2. We talk about the 2000 watt society and our carbon footprint, yet we live in huge homes. We are also driving ever larger, heavier cars. Although they do actually consume less fuel than older models, we now drive much longer distances than we used to. What is more, the number of cars on our roads has almost doubled over the past sixty years.

So the main challenge of urban development is the willingness to cut back on certain things.

Not only. We also need technological progress and structural optimization. We have to encourage closed cycles and acknowledge that our demolition strategies no longer work. Consequently, we should reconsider whether every building that has fallen into disrepair really ought to be torn down and replaced. Buildings from the 1980s and 1990s can actually be expected to last one or two centuries. They can be extended, for example, by adding functional structures such as conservatories. Pioneers in this field are, for example, the architects Anne Lacaton and Jean-Philippe Vassal, who were recently awarded the Pritzker Architecture Prize. For me, these are concepts of the future – where the identity of the past is also preserved.

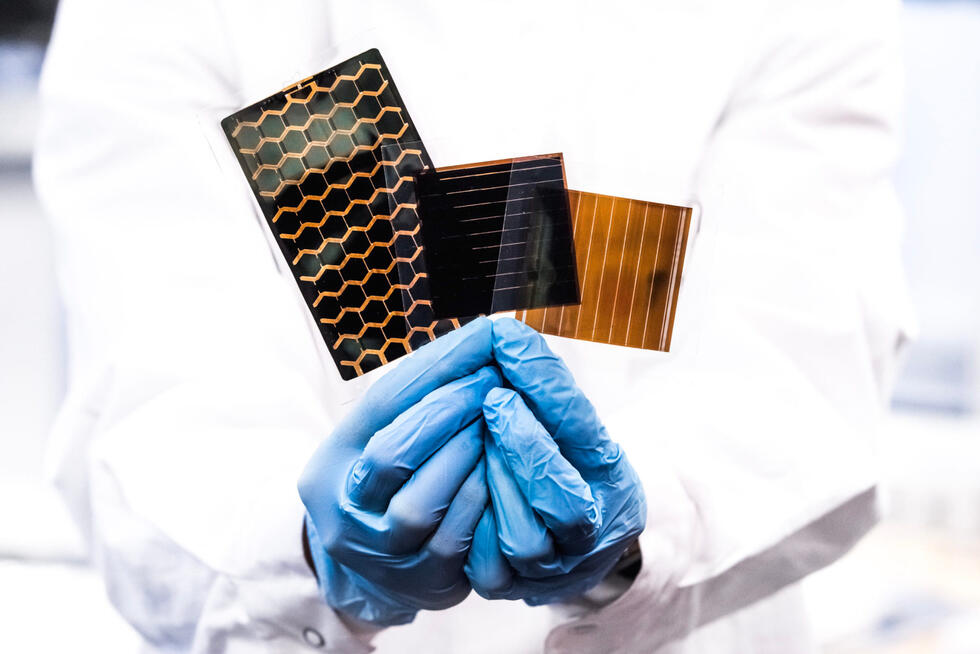

Which materials are gaining in importance?

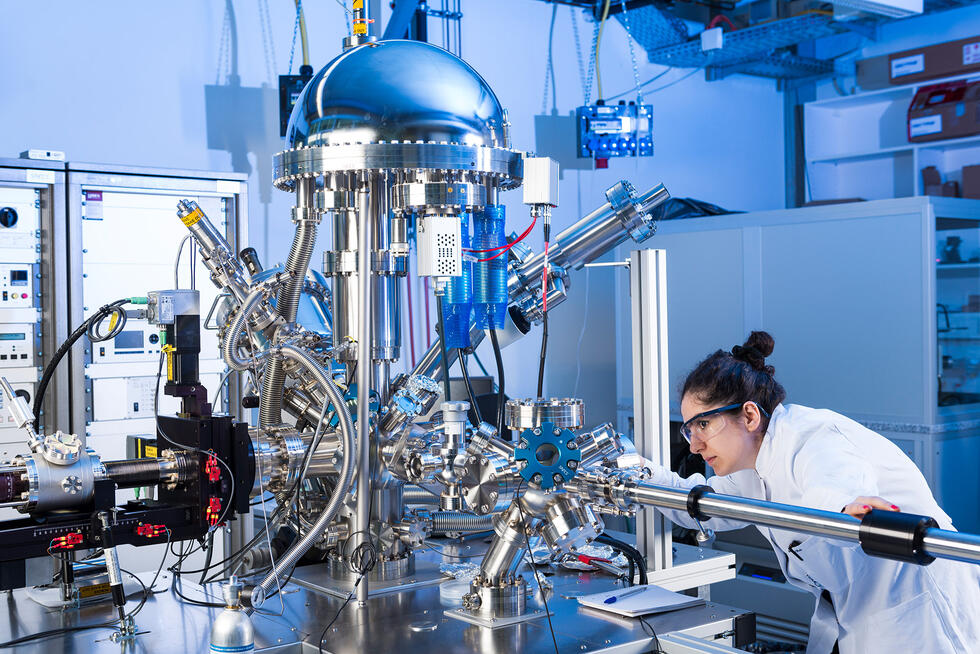

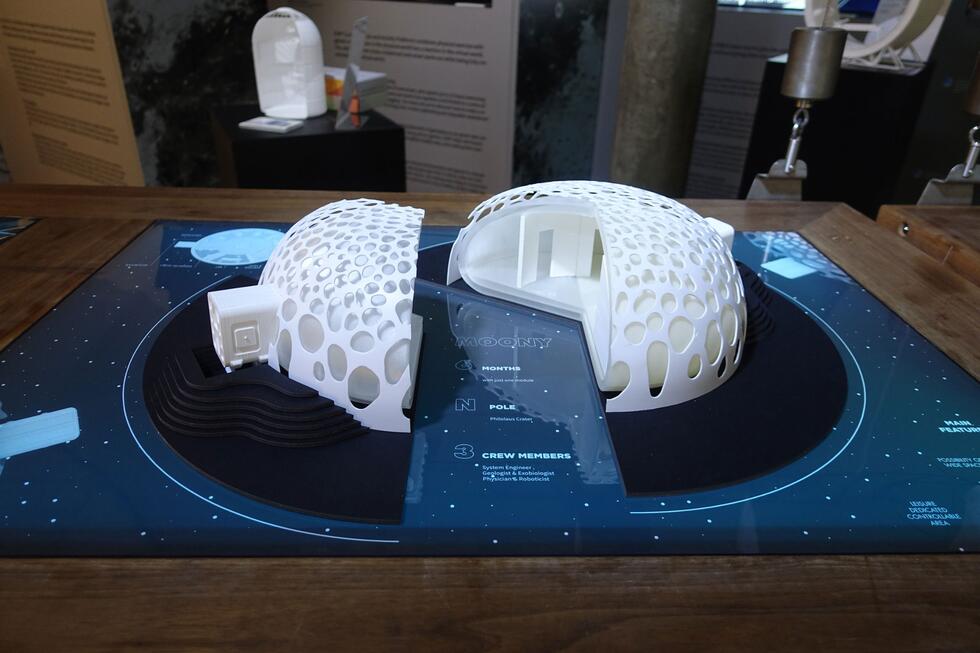

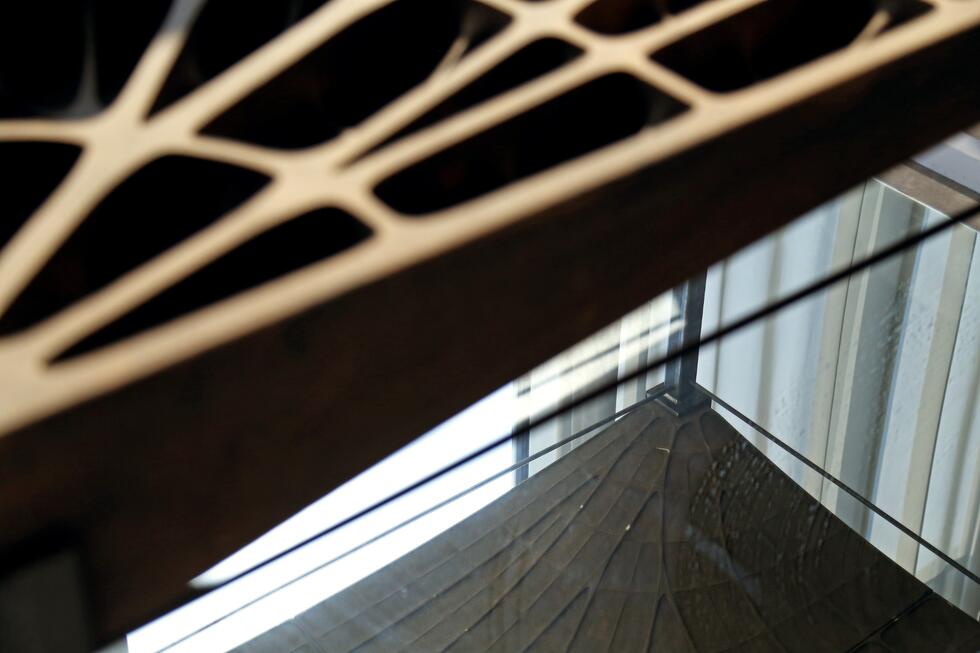

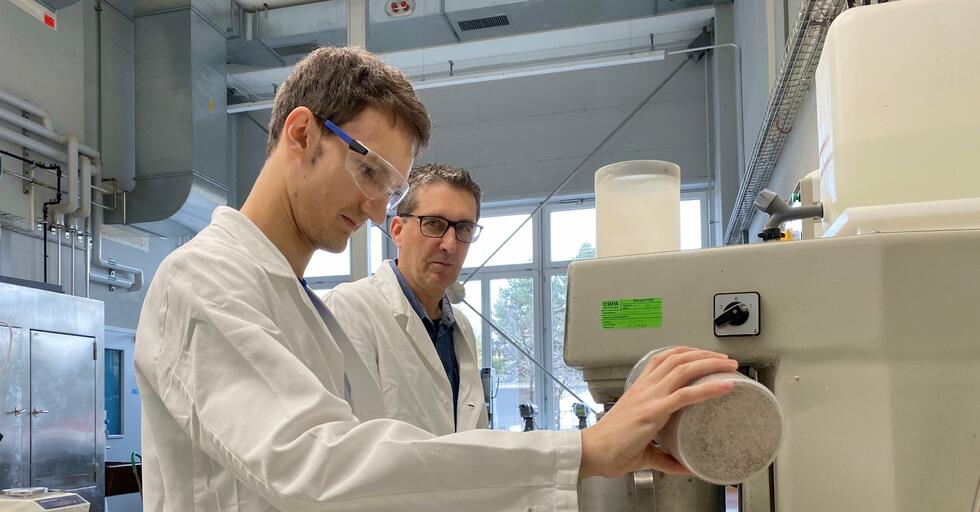

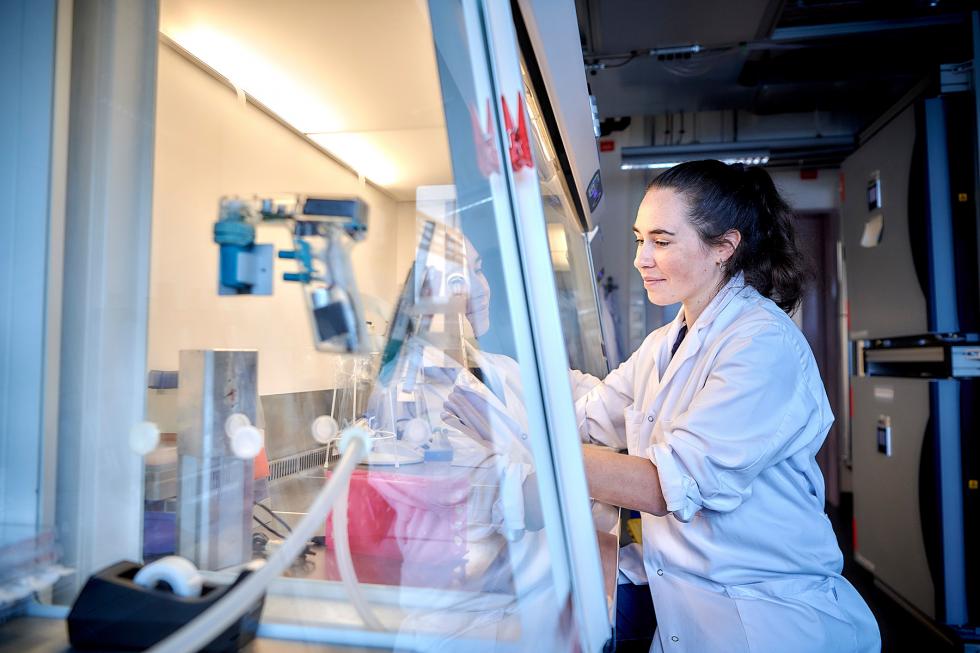

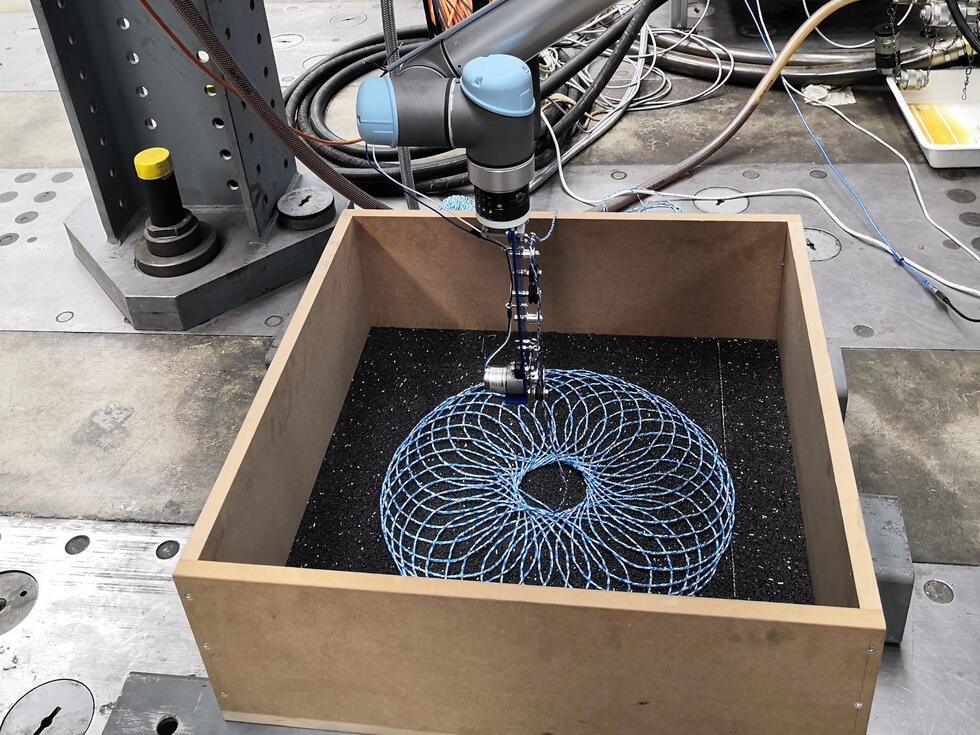

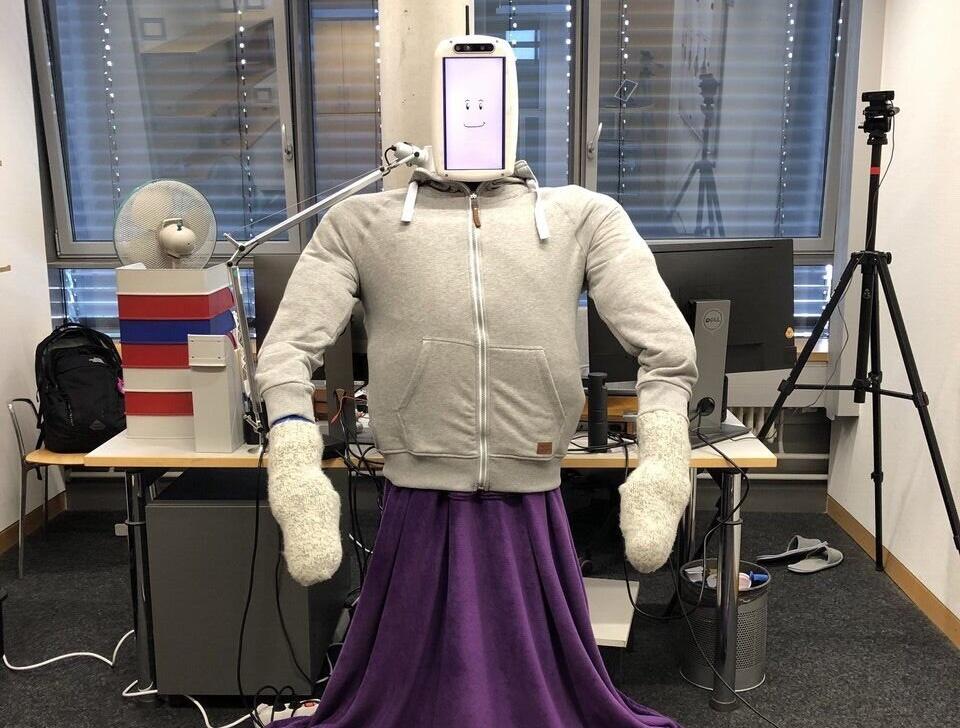

For me, wood plays an important role: Wood is an integral part of our building culture. I also continue to view concrete as central, because basic construction can’t really be accomplished in any other way. But it no longer plays the decisive role and it is rather problematic as far as CO2 emissions are concerned. Here at the Institute for Technology in Architecture [editor's note: ITA at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH) in Zurich], for example, some of my colleagues are experimenting with different technologies, such as digital fabrication, which brings robots to the construction site, or they are testing prefabricated, integrated ceiling systems that can be quickly and inexpensively moved into place. 3D printing for the construction fabrication industry is also a hot topic. The focus is on weight and resource savings, and on speed and simplicity of the systems, which can also be used to modernize existing buildings.

What role does digitalization play?

It plays an enormously important role – and with regard to digital technologies, our institute is at the forefront of research. For example, we developed the robotics-assisted construction of wooden roofs, like the one on our institute building. And by the way, such developments do not mean that jobs are lost, but rather that new ones are created.

So the architects’ role is changing.

We are in a phase of upheaval. Digital skills need to be more deeply embedded in the curricula of architecture and engineering. Nevertheless, students still need to understand how a building works and what structural systems make sense. Architects are increasingly becoming facilitators, bringing together groups with a wide range of skills.

Does this mean that architects rely on good networking?

For me, the magic word is “the collaborative”. Increasingly, the major awards and international attention are going to teams – such as Herzog and De Meuron. Currently, however, there is a trend towards specialization – which I believe is a massive mistake. Architects ought to remain all-rounders, fulfilling the role of ringmaster. There’s no harm in donning a hard hat on a dusty construction site or visiting a factory to gain first-hand experience of how prefabricated building elements are made. I tell my students: “Get dirty!” (laughs)

How important is international networking?

Together with my colleagues, I initiated the Future Cities Lab Global Program. It shows that we can learn from each other. I am a strong believer in a lively international exchange of know-how and ideas.

Are there any cities that serve as role models in this regard?

There are so-called super cities, but I’m skeptical. Singapore, for example, is viewed as very progressive. Here, however, urban development is strongly dictated from above. In Switzerland, on the other hand, we have an open democracy where discourse is possible, which results in broader acceptance.

And what is the situation in Zurich?

Zurich always scores very high in the city rankings. But if you want to rent an apartment in Zurich, you will also find that you have to pay a very high price.

So who are the winners and losers?

The city of Zurich has the stated goal of also providing affordable housing. The co-op model has proven popular. Housing is expensive in Zurich, but it is proportionate to income. We are thus witnessing gentrification. However, certain social classes settling somewhere and displacing others is by no means a new phenomenon.

I can’t help feeling that the inhabitants of Zurich want to turn their city into a village. Is that an accurate impression?

The idea of the village revolves around refuge and safety, around small scales and simplicity – life close to the soil and the availability of things within a reasonable radius. Many people find villages beautiful, but then they pack into jumbo jets and fly to New York. Weird, isn’t it?

What impact will urban development have on the life of city dwellers?

One should not underestimate people: They adapt whatever’s available.

So urban development should create playgrounds for people to realize themselves.

For me, this is one of the most important points – also when it comes to growth: We have to learn to deal with existing structures. But we shouldn’t conserve cities like museums; instead, we can expand on what already exists.

Do you have any examples of how people adapt urban elements?

One example is the Zentralwäscherei on Hardbrücke in Zurich – a former laundry facility in the middle of a residential and industrial district. Suddenly, studios started springing up here. At some point, it turns into something new. That’s what I call a flexible attitude towards existing buildings. It also means not defining residential and commercial spaces so rigidly, but rather to allow open use. Which brings us back to the zoning plan.

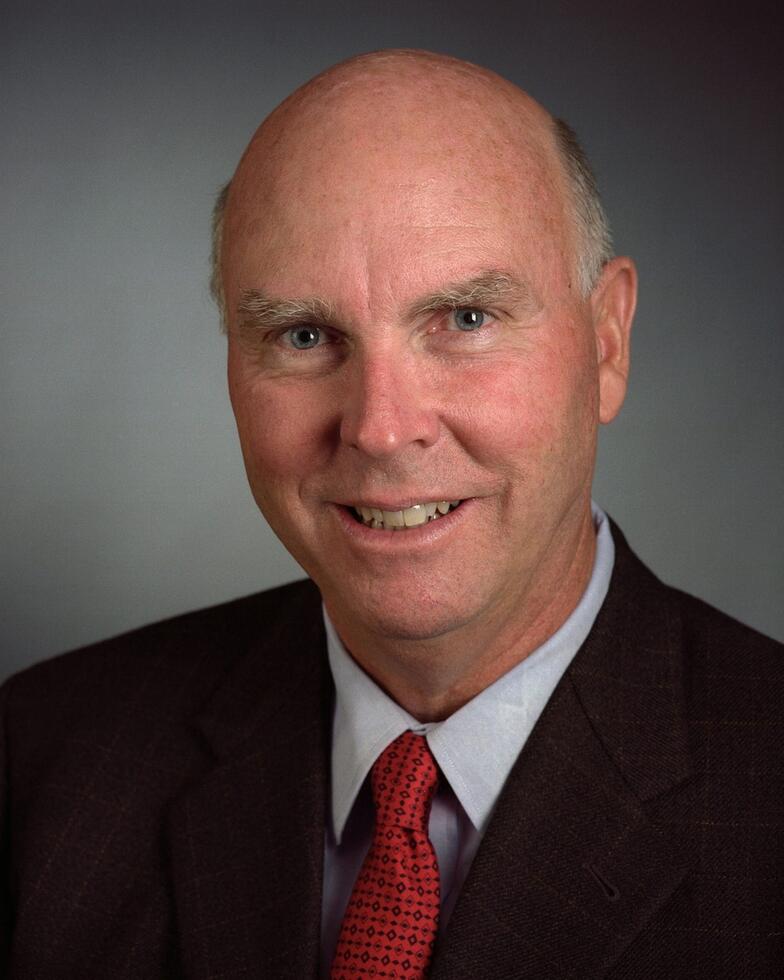

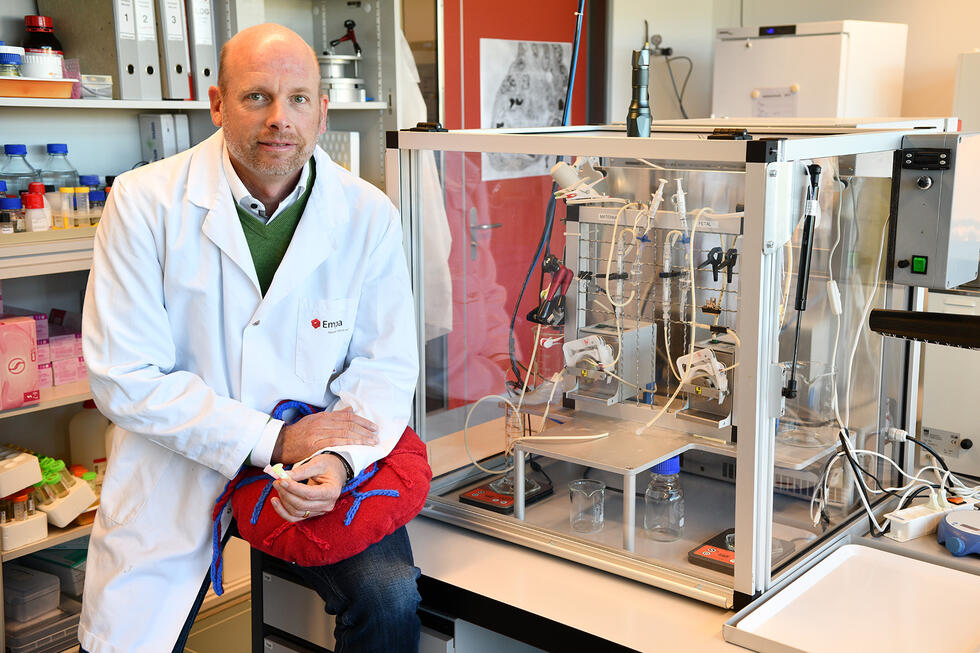

Sacha Menz

Sacha Menz (*1963 in Vienna) is Professor of Architecture and Building Process at the Institute for Technology in Architecture, which he co-founded at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH) in Zurich in 2009. From 2011 to 2015, he was Dean and Vice Dean of the Department of Architecture at ETH. He is also a co-founder and Director of the Future Cities Lab (FCL) Global Program at ETH Zurich. In addition, he runs his own architectural firm, sam architekten. Sacha Menz is married, has one daughter, and is an absolute culinary aficionado.

Photos and written by: Jan Graber