A supersonic comeback

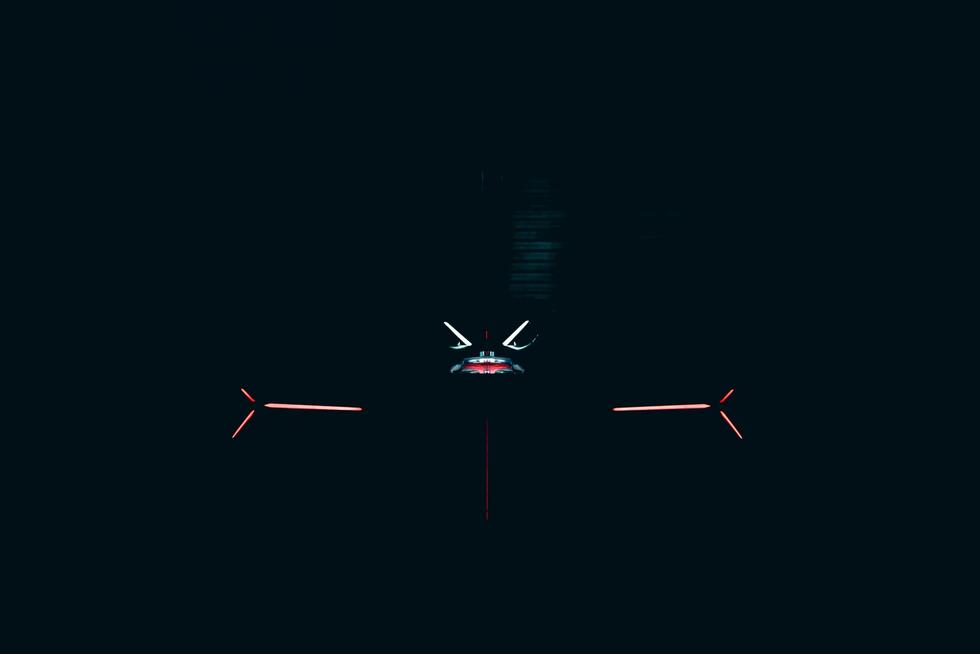

Two decades after the last flight of the Concorde, supersonic aviation technology experiences renewed interest, mainly thanks to fuel-efficient engines and streamlined manufacturing processes. In a hangar near Denver, the fastest, privately-built jet ever built is taking shape.

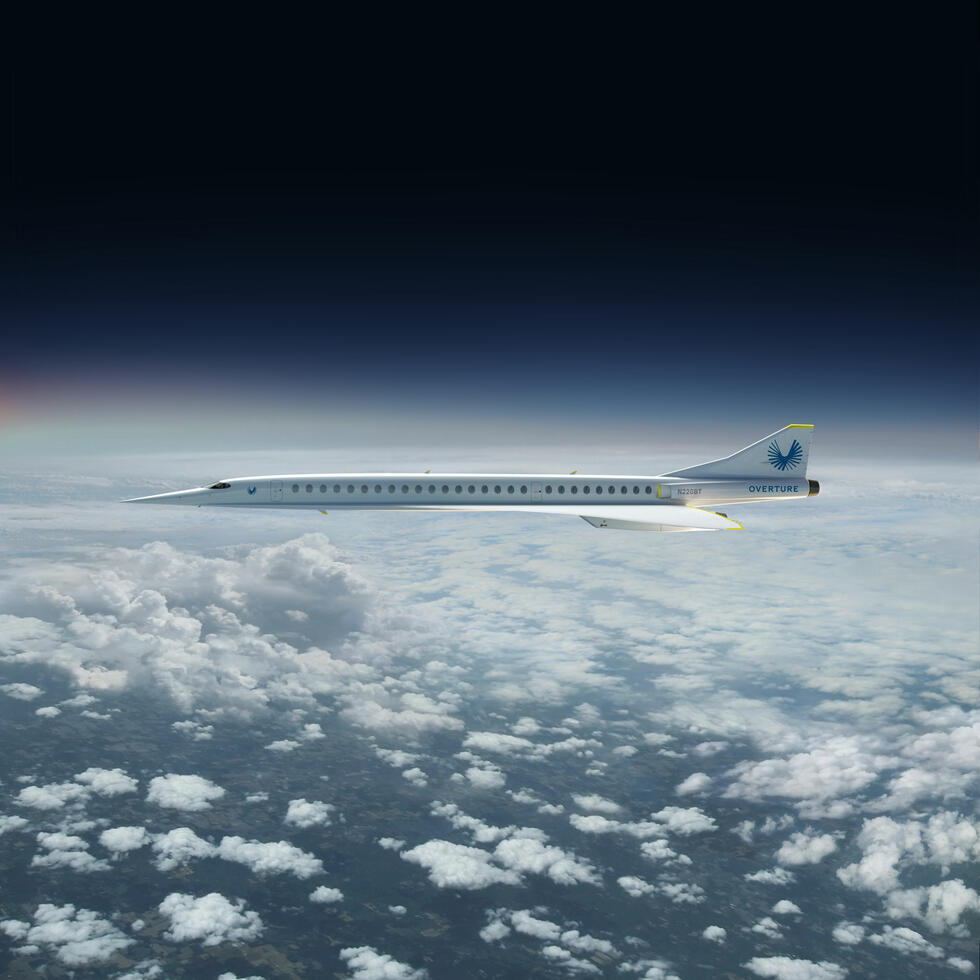

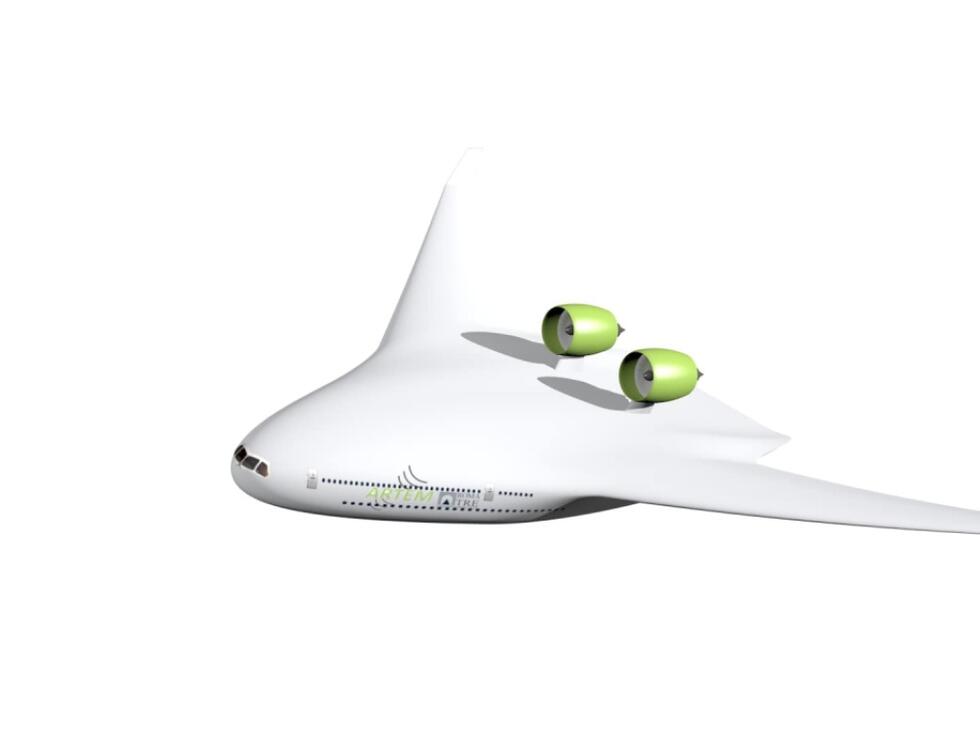

“I never had a chance to fly on the Concorde” explained Blake Scholl (39) to me, when I first met him in a hangar at the edge of Denver’s Centennial Airport. The legendary supersonic jet took its last flight, after 30 years of service, in the fall of 2003; at the time, Scholl was only starting out as a software engineer at Amazon. For the next ten years, he hoped that Boeing or Airbus would release a supersonic successor. During those ten years, he went on to become a successful internet entrepreneur, first at Amazon, then leading and selling a few start-ups, ultimately earning him enough money that he no longer needed to wait for others to come through: In September 2014, he took two million Dollars of his own money and created Boom Supersonic in Denver; the following year, he hired a dozen people from aerospace companies and set out to build the fastest passenger jet in the world. Overture, as it will be named, is designed to carry between 55 and 75 passengers at a maximum speed of Mach 2.2 (at cruising altitude, that would be 2335 km/h) from London to New York in less than three-and-a-half hours so efficiently, that it would cost no more than flying business class today.

After all, it was the operating cost that brought the Concorde down. Burning through 25,680 Liters of fuel per hour at Mach 2, the plane guzzled about a ton of fuel for each of its 100 seats – but on average, every second seat was empty. In their last three years, each of the 14 in service often flew at just 20 percent capacity. Scholl’s take on this is that “it’s not that easy to find a hundred people who are willing to pay 20.000 Dollars for a flight”. Overture will have about half the seats of the Concorde and will use at least 30 percent less fuel, thanks to composite materials and improved aircraft engine technology. Scholl calculates that “the 40 to 70 seats in first and business class of a modern wide-body airplane generate half the sales and all the profit of a flight. We can fit all these profitable seats in one plane, and fly at supersonic speed at the cost of a business class ticket.”

A business class by itself

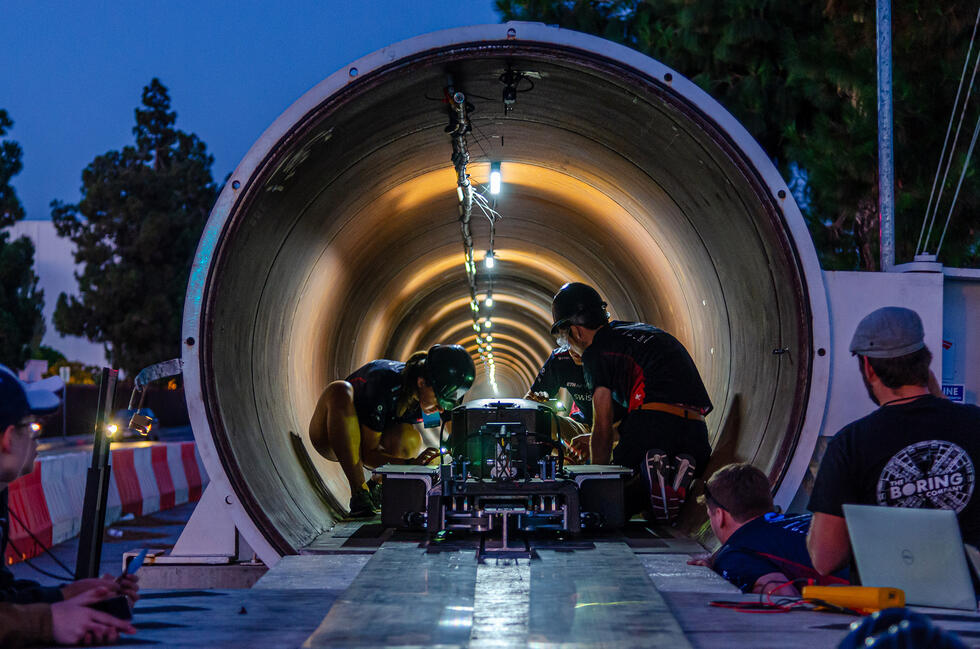

Based on current demand for business class seats, Scholl estimates that he could supply 500 Overture jets at 200 Million Dollars each – generating a 100 Billion Dollar business. Those numbers made his investors’ “eyes light up”, he says: So far, Boom was able to raise 150 Million Dollars; Japan Airlines (JAL) invested 10 Million in 2018, to secure options for 20 Overture-Jets. For his Virgin Group, Sir Richard Branson signed up for 10 Boom jets , bringing the preorder volume to 30 units and a total value of six Billion Dollars. Branson also contributes design know-how and components to the first Boom prototype, a fully functional demonstrator and test model at 1/3 scale, through his spacecraft manufacturing venture The Spaceship Company. Just like the full version, this scaled-down prototype will be able to reach Mach 2.2.

It is intended to prove not just that the Denver startup has the skills to design supersonic aircraft, but that they can also build the faster than Airbus, Boeing, or Lockheed. To speed up the design and development, as well as the certification process with the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), Boom will use as many off-the-shelf components as possible. “Anything that goes into building this aircraft has already been tested and certified: the composite materials, the avionics, the engines – they are already being used and shown to be safe”, explains Scholl. When I first talked to him, he predicted that “Baby Boom” would be ready for rollout and takeoff within two or three years – by now, it has been more than six years, and the XB-1 is still not quite ready. Going supersonic is a slow process, and it needs more expertise than Scholl (who had no experience in aircraft design and building when he started) originally expected. Currently, he has 140 employees working practically around the clock to get the XB-1 ready by summer 2020 for the first test flights above the Mojave Desert in Nevada. Initially, he thought that he could accomplish the task with 40 or 60 people.

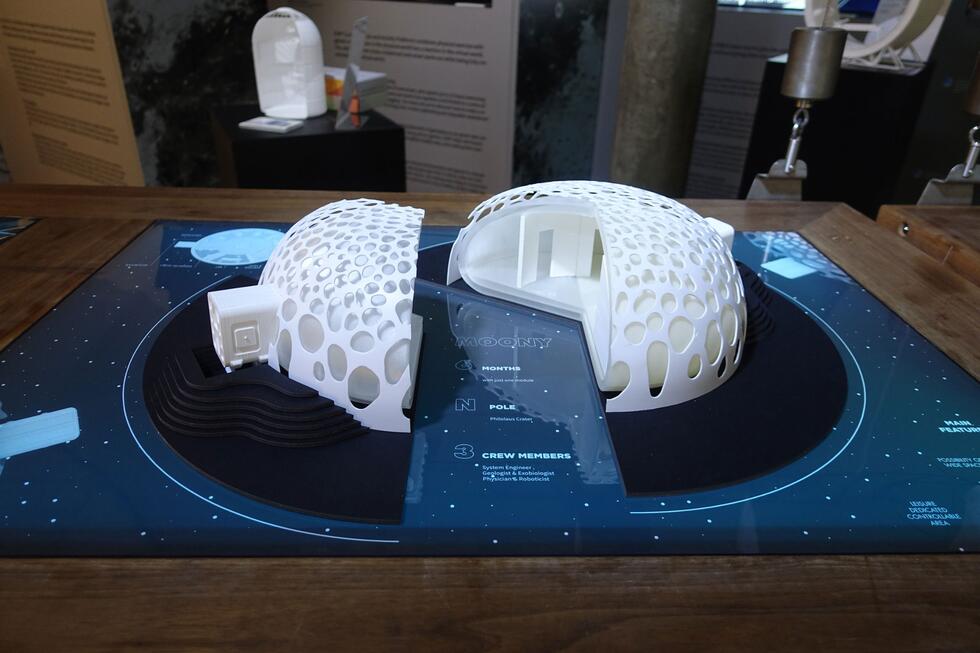

Officially labeled XB-1 and lovingly nicknamed “Baby Boom”, it is the first privately built supersonic jet since the Concorde.

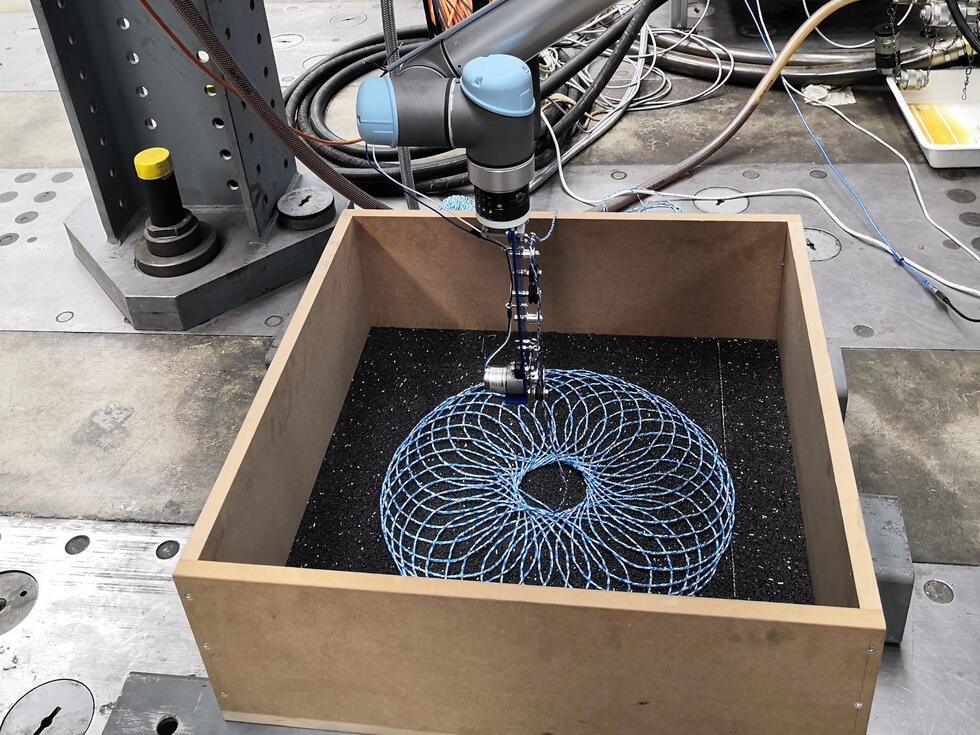

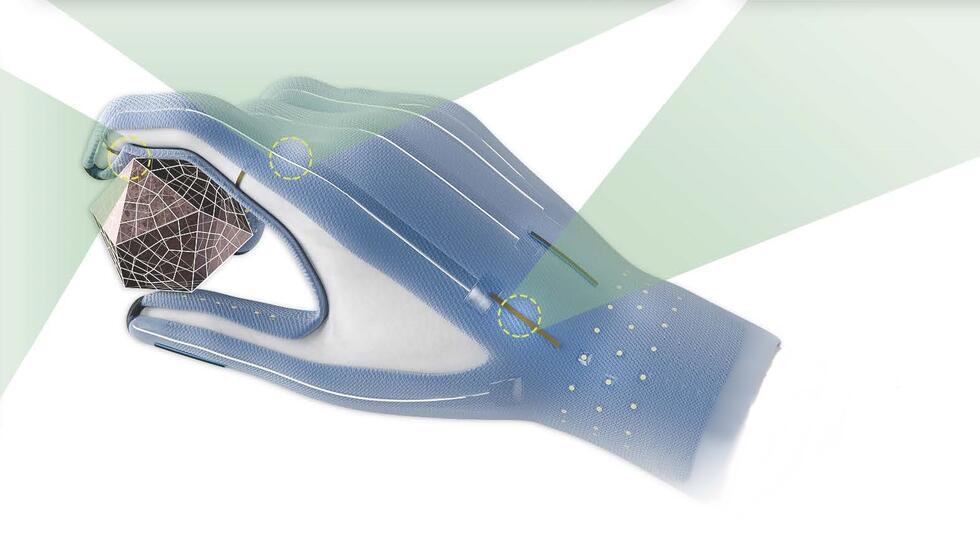

But three days before Christmas 2019, the XB-1 prototype started to take shape: The cockpit and the nose landing gear were bonded into the carbon-compound fuselage. To make sure that the bonding adhesive cures to its maximum strength, a custom-built “oven”, 15 meters long and three meters high, was installed in the hangar and had to be lowered from the ceiling. The delta wings have a span of 6.40 and are one integrated component, made from carbon fiber and titanium, which are covered in a heat-resistant skin. The rear fuselage will be made from titanium to be able to withstand the weight of the three engines (about one ton, combined) and, most importantly, the heat they generate, which can reach up to 430O Celsius; this part still awaits completion.

Gallery of XB 1

Fusing the fuselage: Bonding the cockpit into the carbon-fiber fuselage was a delicate 20-hour process that took a synchronized effort from the entire Boom team

Still searching for the right engine

The three engines are actually the only parts of the XB-1 that are already fully functional: The prototype will be powered by three J85-15 engines, with a combined thrust of 57.71 Kilonewton – that’s about one third of the Concorde’s thrust, and at top speed, this equals around 46’000 hp. This turbojet has been around for some time now: Developed by General Electric in the 1950s, it was primarily intended for military use. Although GE stopped building the J85 in 1988, over 6000 are still in active service (and GE gas guaranteed service and spare parts until 2040); a well-maintained jet engine is just as good as a new one. It must be mentioned that the J85 jet engine was originally designed for subsonic speeds, but with a few modifications, like a smaller intake fan, it is possible to boost it to supersonic capabilities. For additional thrust, the XB-1 will be equipped with afterburners.

But afterburners are noisy; for that reason, Overture is designed not to use these thrust boosters. That will not only increase passenger comfort, but also ensure that the plane meets noise restrictions of international airports. The benchmark for noise reduction, according to Scholl, is landing at London Heathrow Airport at night, which lies in “the most noise-sensitive neighborhood in the world”. The challenge is that, so far, no supplier for such an engine could be found. Which is cause for concern, according to Richard Aboulafia, a leading aviation analyst, who tells me that an aircraft is normally designed around the engines, not vice versa.

Supersonic flight for everyone?

Therefore, it remains to be seen if Overture remains on track to be launched “in the second half of the 2020’s” (Scholl). But timing is becoming an issue; one year ago, Boeing replaced Airbus and Lockheed as partner for the aircraft design company Aerion in Reno (Nevada); rumor has it that Boing was willing to invest more than 100 Million Dollars, to boost Aerion’s supersonic project AS 2. This business jet will seat around 12 passengers, which makes it substantially smaller, and – at a top speed of Mach 1.4 – also much slower than Overture, but AS 2 will aim for a similar market, with a production volume of 400 jets over the next two decades. But if he’s concerned about the competition, Blake Scholl does not show it: “Bring them on”, he told me when I last talked to him again, a year after our first meeting. He actually welcomes the renewed interest in supersonic flight: More competition will also drive demand, and increased demand will lead to more efficient technology, especially for engines and aerodynamics. “A few generations from now, supersonic flight might become extremely cheap”, prophecies Scholl. Cheaper than today’s subsonic flights: “Going anywhere in the world within a few hours, and for no more than 500 Dollars – that’s our long-term goal. And that is no science fiction.”