Are CO2 absorbers the saviors of the climate crisis?

In the fight against climate change, gigatons of carbon dioxide will have to be removed from the atmosphere over the course of the century - using so-called carbon dioxide removal (CDR) technologies are giving people new hope.

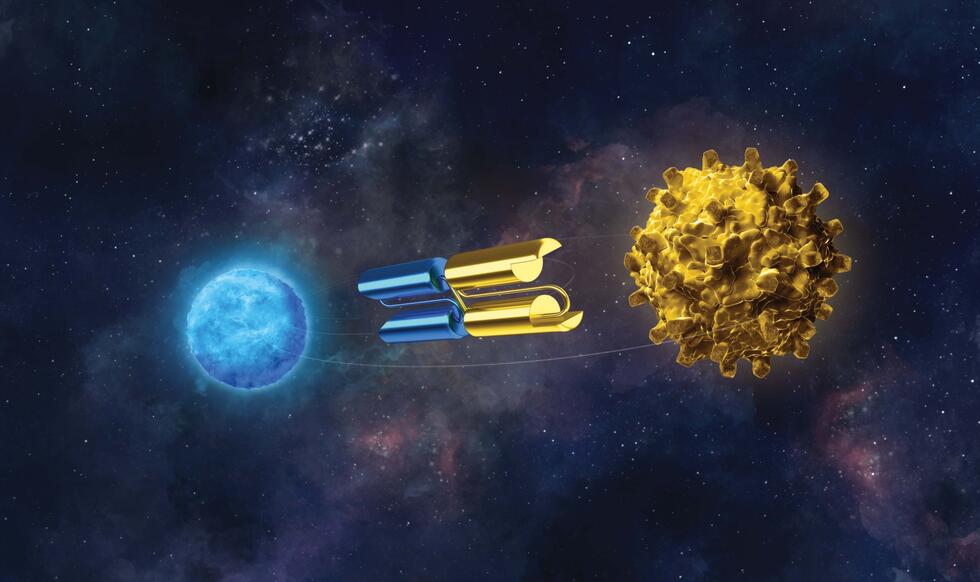

Why don't we just suck all the carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere and bury it deep underground or recycle it as a raw material? That would be a great contribution to the fight against climate change. That's right. And that is exactly what Carbon Dioxide Removal (CDR) does. A collective term for technologies that filter CO2 out of the air or exhaust gases so that the climate-damaging gas cannot heat up our world any further.

CDR is a hype. On the one hand, because it sounds like an ingenious and simple solution to what is probably the biggest problem of our time. On the other hand, because even the IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) writes in its latest assessment report that CDR is “indispensable” for reducing global emissions to net zero. And for the following reason: in all calculated scenarios in which the 1.5-degree target is still achieved, CO2 must be removed from the atmosphere.

It won't work without CO2

But the technologies are not fully developed. CDR is miles away from the “extraction volume” that will be necessary in the future according to the IPCC. However, according to the report “The State of Carbon Dioxide Removal”, many people in decision-making positions are unaware of this fact. The first global assessment of CDR measures shows that governments around the world are neglecting research and development of the technologies. Many countries will therefore fail to meet the “net zero emissions” target in the Paris Climate Agreement. Net zero means capturing as many quantities of climate-damaging gases as are emitted - and this is only possible with CDR. Otherwise, the countries would have set themselves a “zero emissions target”. And that is very unlikely because many sectors will continue to burn fossil fuels.

Many countries will therefore fail to meet the “net zero emissions” target in the Paris Climate Agreement.

Climate researcher Jan Minx is one of the authors of the report. In January, he said at the presentation of the results: “We see a considerable gap when we compare the planned CO2 removals in the climate protection plans of the states with the quantities actually required for climate protection.” Minx and his team modeled how much more CO2 CDR technologies would have to remove from the atmosphere in 2050 - compared to today - in order to achieve the climate targets. The result: 1,300 times the amount. This is the cautious scenario in the event that global CO2 emissions fall considerably. In another scenario, in which less CO2 is saved over the next 27 years, it is even 4,000 times more.

Minx and his team modeled how much more CO2 CDR technologies would have to remove from the atmosphere in 2050 - compared to today - in order to achieve the climate targets. The result: 1,300 times the amount.

2050 is the year in which, according to the IPCC, global emissions should reach net zero. However, Minx's team did not just choose this year because it also represents a kind of caesura. According to them, the period prior to this is primarily about avoiding and reducing greenhouse gases. In the second half of the century, however, CO2 removals dominated climate protection. Their task: to offset the residual emissions that occur even in a world trimmed for sustainability. For example, from air travel, animal husbandry or the production of concrete.

Reforestation in particular has been efficient so far

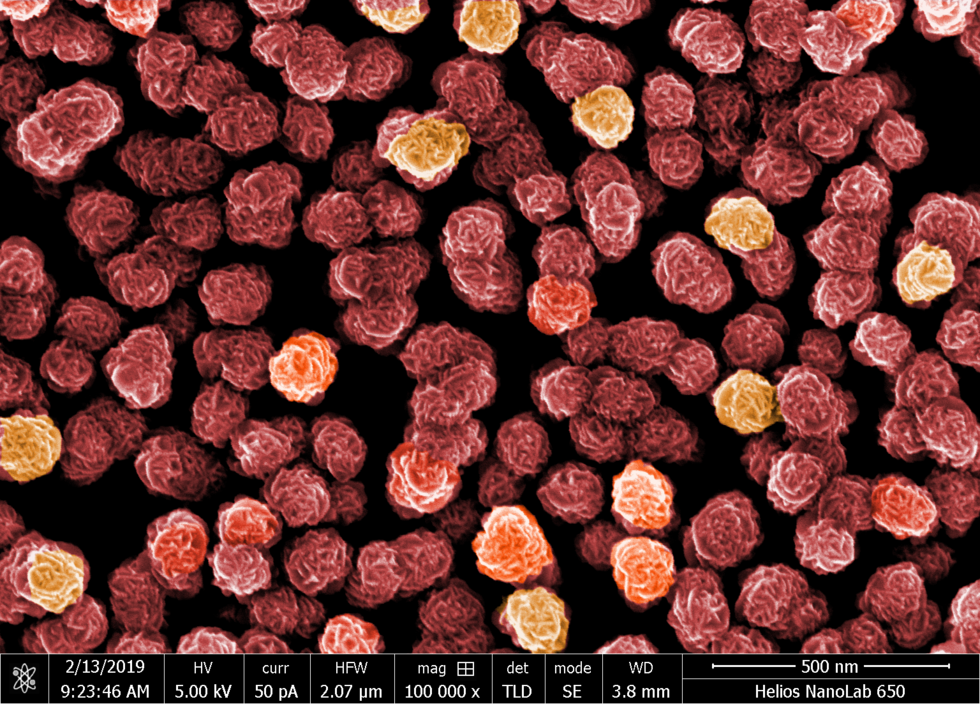

It can only go hand in hand: in order not to be too dependent on CDR in the future, CO2 emissions must be reduced quickly and drastically. At the same time, the expansion and development of new extraction methods in particular (see info box) must be driven forward. This is urgently needed, as they have so far only captured marginal amounts of CO2 - around 0.002 gigatons per year. In comparison, reforestation and the management of existing forests bind a thousand times as much. However, there is a danger in relying on this alone: the consequences of climate change are already resulting in increased drought and more frequent forest fires. This is why the IPCC classifies CO2 storage in trees as far less safe and permanent than storing the gas in rock layers underground, where it mineralizes over time.

Despite its great importance in the future, the authors of the CDR report see little political support for the technologies.

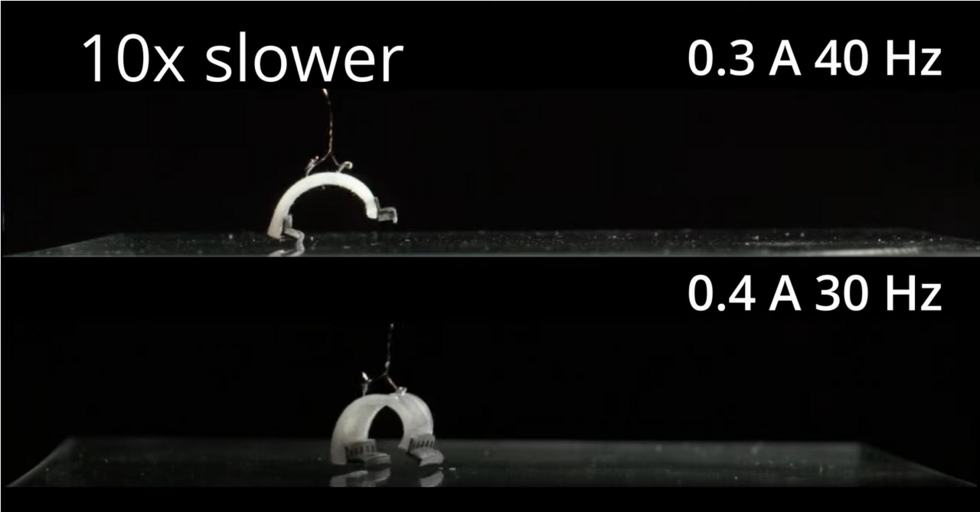

This could be because their current level of development is overestimated. Minx said in January: “In the case of new extraction methods - such as CO2 capture and injection in the production of bioenergy or direct air capture - we are almost at zero. At the same time, they are dominating the public debate." This is why industrial-scale plants need to be put on the rails as quickly as possible; they will certainly not fall from the sky.

First “million-ton power plant” to be built in 2025

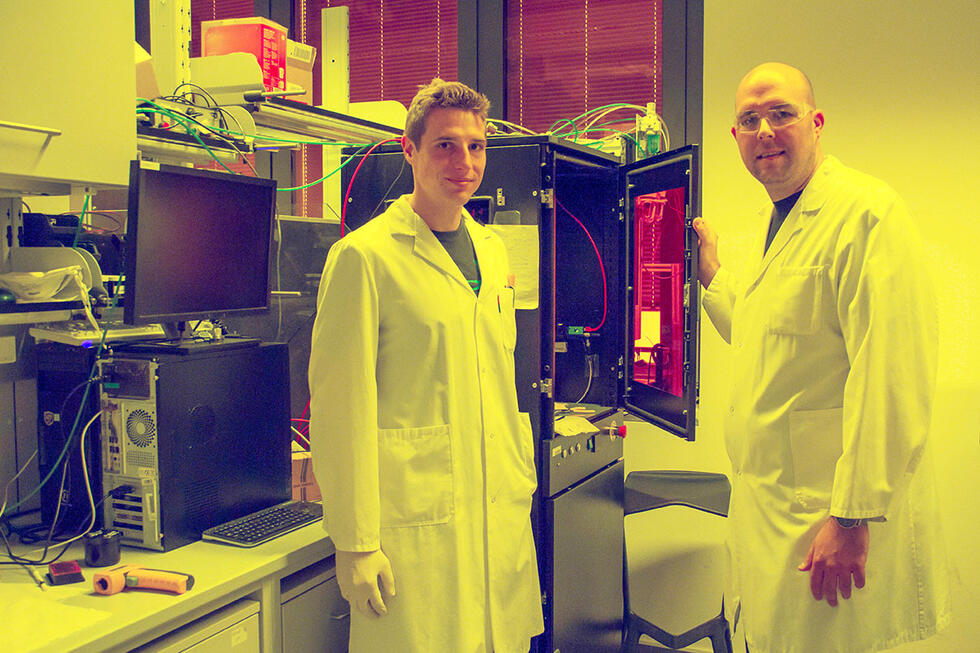

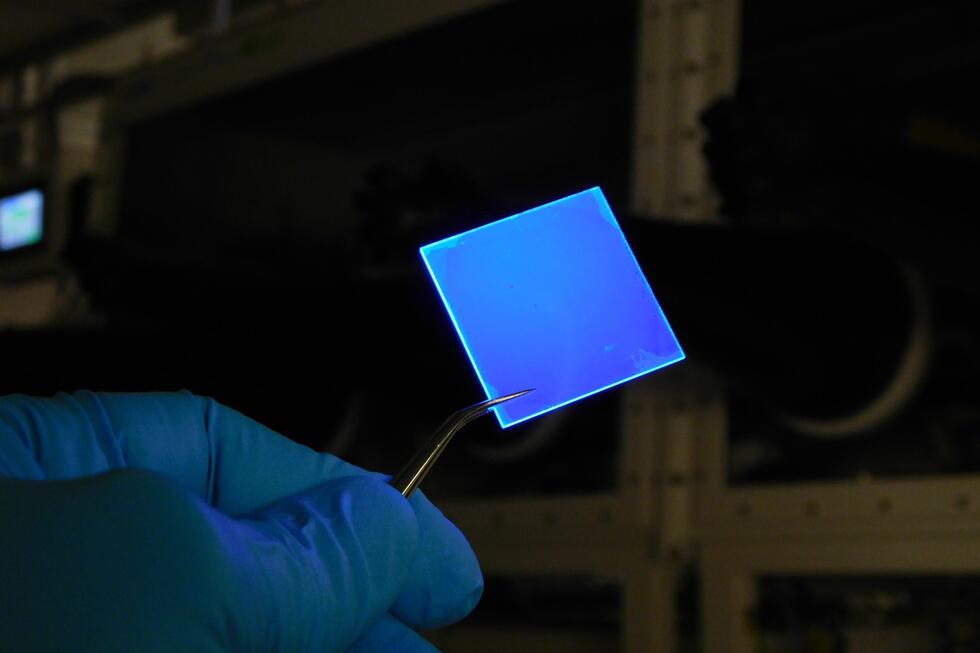

The Swiss company Climeworks could serve as a role model. It operates what is probably the best-known and currently largest DAC plant in the world: “Orca”. It is located on the Hellisheiði plateau in Iceland and has been sucking around 4,000 tons of CO2 out of the air every year since 2021. The gas is then mixed with water and pumped around 1,000 meters into the depths, where it hardens in basalt rock over a period of around two years and is thus removed from the atmosphere forever. The plant obtains the energy for the complex process from a nearby geothermal power plant.

The Swiss company Climeworks could serve as a role model. It operates what is probably the best-known and currently largest DAC plant in the world.

Climeworks is already the first company or private individual to offer CDR extraction for paying customers. They are well known: Microsoft, Stripe and Shopify are reducing their CO2 footprint in this way. At least a little. This is because the quantities of greenhouse gas collected with Orca are small compared to the companies' total emissions. Microsoft itself estimated in 2020 that it emitted around 16 million tons of CO2 that year.

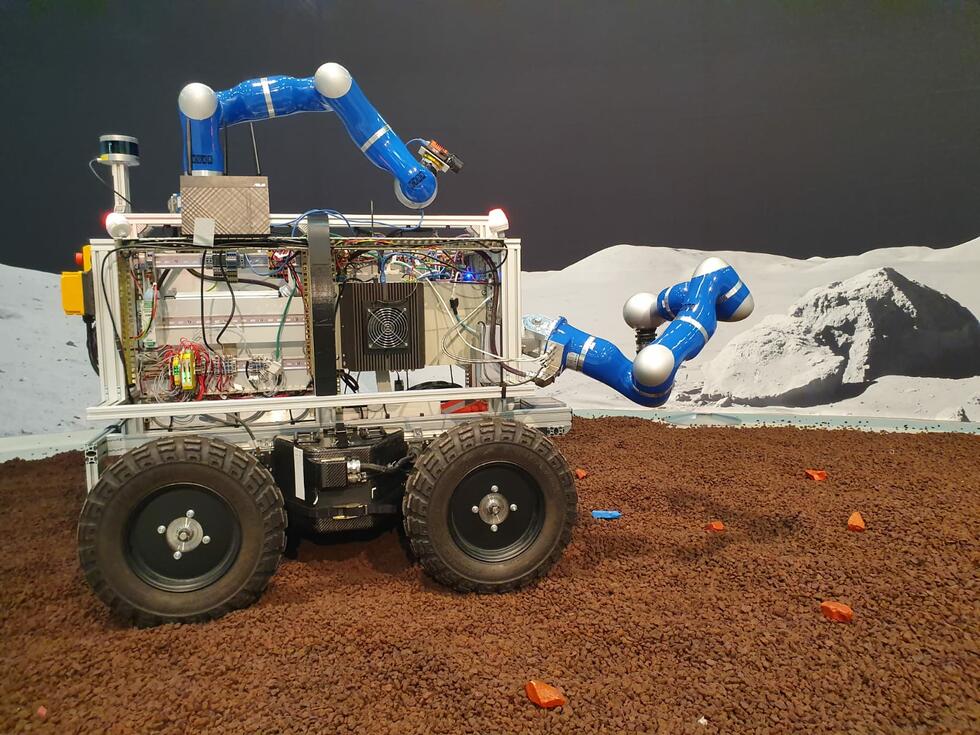

Nevertheless, the Icelandic company Carbon Engineering is planning the first one-million-ton power plant for 2025.

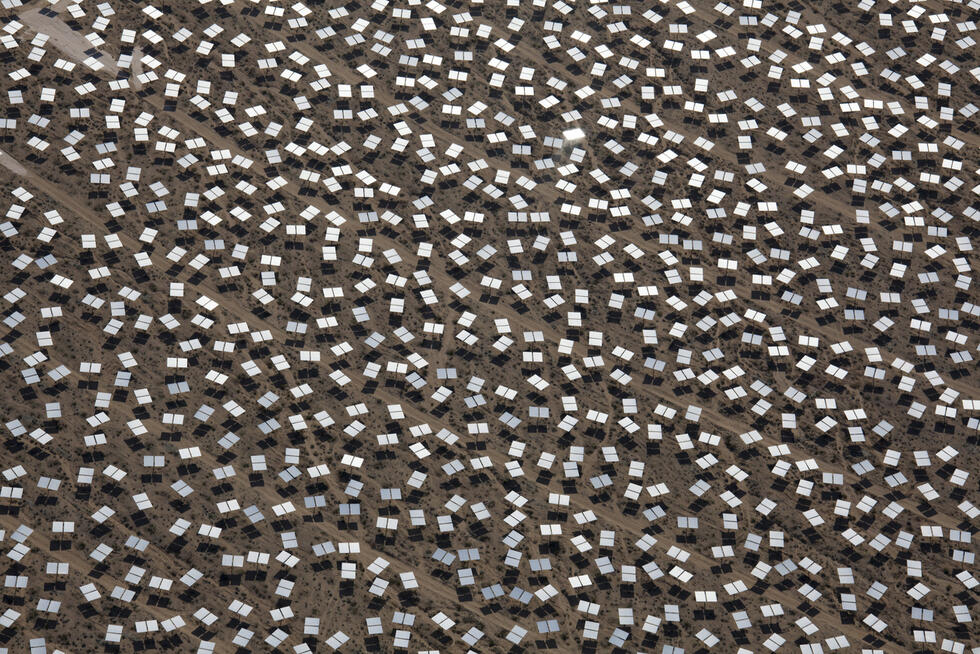

In comparison, the output of “Mammoth” still seems tiny. This is the name of the second Climeworks plant, which is currently being built and is expected to capture 36,000 tons of CO2 per year. Nevertheless, the Icelandic company Carbon Engineering is planning the first one-million-ton power plant for 2025. And “Dreamcatcher”, a CDR plant being built in Scotland, is also expecting a “production volume” of half a million to one million tons of CO2 from 2026.

Headwind from environmental associations

However, there are far too few of these lighthouse projects. This becomes clear when you put their capacities in relation to global emissions. These recently stood at around 37 gigatons and are rising. After a dip during the coronavirus pandemic, global CO2 consumption reached its highest level on record. It is therefore very likely that thousands of CDR plants will have to be built by the middle of the century. However, this could fail not only due to a lack of political guard rails, but also due to headwinds from the population.

However, there are far too few of these lighthouse projects. This becomes clear when you put their capacities in relation to global emissions. These recently stood at around 37 gigatons and are rising.

It is far from certain that citizens will accept gigatons of gas being pumped under their villages and towns, lakes and oceans. This is shown, for example, by a statement from BUND, Germany's largest environmental association. It recently spoke out against carbon dioxide landfills in general and condemned the government's plan to allow “industrial-scale CO2 repositories”. The association's chairman, Olaf Bandt, explained: “Industry wants to dump its climate-damaging exhaust gases under the North Sea instead of reducing emissions.” However, the oceans are not humanity's garbage dump.

Social question: plate or storage?

"That's a fundamental position. It would be better if we talked openly about the dangers and opportunities of the technologies,” says Danny Otto. He works at the Helmholtz Center for Environmental Research in Leipzig and has been investigating how carbon dioxide removal is perceived by the public for years. As part of an international team, he conducted a representative survey in Germany, Norway, the Netherlands and Greece. It shows: “People are aware that there are technical risks. For example, many are critical of storage under the seabed. What is interesting, however, is that delayed decarbonization is seen as similarly risky." The two are linked because the coal industry has long been promoting carbon capture and storage (CCS) as a solution. A process that separates CO2 directly from power plant exhaust gases so that it can be injected. However, CCS has been tested in different variants, in some cases for decades. Without the big breakthrough. “Some of our interviewees have a very negative view of the technology,” says Otto, “because it could mean an extension of coal-fired power.”

And there are as yet unseen conflicts that will come to light through the increased use of CDR, Otto believes: “Some of the technologies are very land-intensive, others consume a lot of energy and water, while others use large quantities of biomass. All finite resources that raise distribution issues." Like this one:

Should huge agricultural areas be planted with monocultures to bind CO2 from the air instead of grain, fruit and vegetables?

Beware of tipping points in the climate

“The answers to these and similar questions will determine how quickly the expansion of CDR technologies progresses,” says Otto. For him as a sociologist, a differentiated debate is therefore necessary. However, he warns against a narrative that is already cropping up in debates today: CDR as a “techno-fix”. This is the name given to innovations that are not yet fully developed but could hypothetically solve a problem. In relation to climate change: If CO2 removal methods could recapture all harmful emissions in the future, why should we change our behavior in the here and now? "The worst thing would be for politicians to present CDR as a wild card that can solve the climate crisis. Because that's simply not true." All scientific findings show that “we must first and foremost drastically reduce our CO2 emissions”.

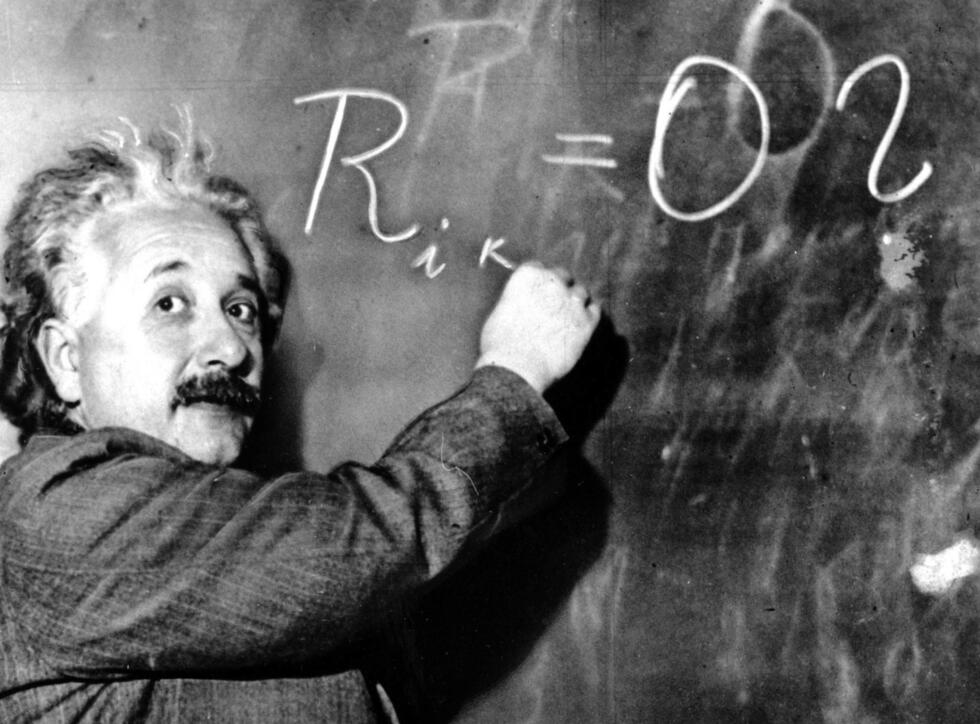

The reason is this: if CO2 is released unchecked until CDR technologies are scaled up and ready for use, the earth will heat up by far more than just 1.5 or 2 degrees. This would not only make entire regions uninhabitable, but would also reach critical tipping points. The Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research explains that these are “large-scale components of the Earth system” that exhibit threshold behavior. For a long time, little happens until a threshold is reached, then entire coral reefs die or permafrost thaws. This becomes more likely the warmer it gets. And: even if the world cools down again later, i.e. falls below the threshold value, “the new state of a tipping element can be maintained”. This is why carbon dioxide removal is not an equivalent alternative to reducing CO2.

Every ton of carbon dioxide avoided is therefore far more valuable. Sociologist Otto puts it this way:

“Capturing CO2 again costs us a lot more energy, water, land and ultimately money. Nevertheless, CDR will be indispensable in the future."